29 August (evening) and 30 August (matinee), 2014. State Theatre, Victorian Arts Centre, Melbourne

Stanton Welch made his new version of La Bayadère for Houston Ballet, of which he has been artistic director for ten years. Its premiere was in 2010. He has now restaged it for the Australian Ballet, where he still holds the position of resident choreographer.

It was always going to be a problematic ballet: an updated version of a work that is entrenched in nineteenth-century cultural values where countries beyond Europe were regarded as little more than examples of exotica, and were represented as such in the theatre. Choreographically, Welch’s Bayadère makes passing references to traditional Indian greetings and hand movements from forms of Indian dance. There are also plenty of attitudes (the ballet step) with angular elbows and hands bent at the wrist, palms facing upwards. They remind us of a dancing Shiva. But there is also a lot of waltzing at certain points and the mixture doesn’t ring true today. So much of what we can accept from a production that claims to look back to the original (Makarova’s production for example), we can’t accept from a new production made in the twenty-first century. It all becomes a frustrating jumble.

So too with the costuming. There are no tutus (thankfully) until the Kingdom of the Shades scene, although there is a confusion of costuming, especially with Solor who is dressed like a balletic prince in tights and jacket while everyone else has a costume that approximates an Indian-style outfit.

My enjoyment of the work depended very much on the casting. The first show I saw, with Lana Jones as Nikiya and Adam Bull as Solor, was a lack-lustre performance, which only highlighted the feeling that the work was a cultural and choreographic jumble. While Jones’ first solo was beautifully danced—she has such a fluid upper body—she and Bull were not connecting and it seemed like a very sullen pairing. Robyn Hendricks as Gamzatti, whose villainous nature Welch has strengthened nicely, overplayed the role somewhat and didn’t look good in that harem costume, which reveals the rib cage rather dramatically.

In that first viewing, I loved the two children who accompanied Solor’s mother wherever she appeared. They were an absolute delight and took an active interest in everything happening on stage. And Vivenne Wong executed the first solo in the Shades scene with precision and attack—those relevés on pointe down the diagonal were spectacular.

In a second viewing I had the pleasure of seeing Amber Scott as Nikiya and Ty King-Wall as Solor. My interest in the work soared.

King-Wall and Scott danced beautifully together and their various pas de deux were silky smooth and imbued with tenderness. This was the first time I have seen King-Wall in a principal role since he was promoted and he certainly lived up to that promotion, both technically and in terms of successfully entering a role and developing a partnership. Ako Kondo as Gamzatti once again danced with superb technical skill. Perhaps she was a little too nice for the role in its new guise, but she engaged well with Laura Tong as Ajah, her servant, and it is impossible not to be swept away by her superb dancing.

The issue of Indian references aside, Welch’s choreography is always interesting to watch. I have written elsewhere that I think his best works are abstract rather than story ballets and I enjoyed watching how he structured scenes for larger numbers of people in Bayadère. His choreography for the Rajah’s four guards was simply constructed but often surprising in the way each came forward for a mini solo. And later, during the wedding celebrations for Solor and Gamzatti, Welch handled a bevy of guards and guests easily and maintained interest, despite the waltzing, in each of the different groups throughout that sequence of dancing.

Design-wise, Peter Farmer’s chaise-longue, on which Solor reclined to smoke his opium before the shades of Nikiya began their procession down the ramp, was gorgeous. Its luscious curves gave it an art nouveau feel and its back reminded me of the underside of a mushroom, magic mushrooms no doubt.

This production of La Bayadère is full of melodrama, a ‘cat fight’ between Nikiya, Gamzatti and Ajah; people being killed left right and centre; appearances by men in gold paint; and temples tumbling into ruins. But Petipa’s choreography has been maintained in certain places and, with a good cast, the story speeds along and much can be forgiven.

Michelle Potter, 2 September 2014

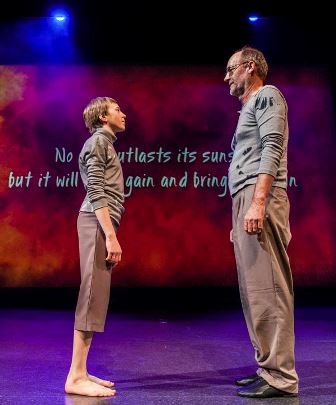

Featured image: Ako Kondo as Gamzatti in Stanton Welch’s La Bayadère. The Australian Ballet, 2014. Photo: © Jeff Busby.