Renewed interest in my research into the 1934–1935 tour by the Dandré-Levitoff Russian Ballet has prompted me to post further material that originally appeared as appendices to my article on the tours. The article appeared in Dance Research (Edinburgh University Press), 29:1 Summer 2011.

Below is a list of divertissements that were performed in Australia, Appendix B of the Dance Research article. In a previous post I listed the repertoire and schedule of performances (Appendix A of the Dance Research article) but listed only the title ‘Divertissements’, where appropriate, without giving details.

APPENDIX B: AUSTRALIAN DIVERTISSEMENTS

This list of divertissements, the short pieces that usually concluded each program, has been constructed from programs for Australian seasons in Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. Occasionally alternative names were used and they have been included preceded by a slash. Occasionally, too, Promenade (Old Vienna) and Polovtsian Dances were listed in advertisements as divertissements rather than as main program items. They have not been included on this list and have been kept as part of the main repertoire schedule. The list may not be complete and other divertissements may have been in included outside Australia.

| Abhinaya nrita (Authentic Hindu music/Hindu melody) Bluebird (Tschaikowsky) Dance of the doll (Kiurci) Dance of the doll (Salvado) Dance of the hours (Ponchielli) Danse russe/Russian dance (Bakalienikoff) Etude plastique (Liszt) Grand pas classique (Deldevez) (Grand) pas hongrois classique (Glazounoff) Guitana/La gitana (Salvado) Ice maiden (Grieg) Indian tribal dance (Minkus) Japanese dances (Original Japanese music) L’oiseau (Schumann) Magyar tanc/dance (Bartok) Mexican dance (Padilla) | Negro fire-worship dance (Stempinsky) Nocturn (Schumann) Pas de fleurs (Tschaikowsky) Pizzicato (Gillet) Spanish character dance (Romero) Spanish dance (Albeniz) Spanish dance (Granados) Tarantella (Rossini) The faun (Debussy) The love song (Kreisler) Toreador Spanish dance (Julio Garson) Trepak (Launitz) Valse (Fetras) Valse (Strauss) Valse brilliante (Chopin) Voices of spring (Strauss) |

***********************************

Below is a list of dancers who performed during the Australian leg of the tour, Appendix C of the Dance Research article.

APPENDIX C: DANCERS PERFORMING IN AUSTRALIA

Press reports on the arrival of the company in Australia noted that it comprised 36 dancers. (‘The Russian Ballet arrival in Sydney’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 1934, p. 12). Listed below, with some explanatory notes, are those whose names I have found appearing on programs or mentioned in the press, adding up to less than 36 dancers.

Women:

Olga Spessiva (Brisbane and Sydney) and Natasha Bojkovich with

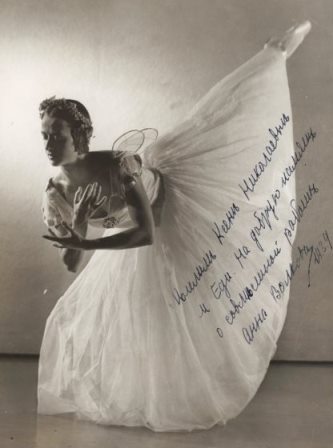

Kathleen Crofton, Lisa Elem, Juliana Enakieff, Tamara Djakelly (Giakelly), Eileen Keegan, Raia Kuznetzova, Molly Lake, Eleanora Marra, Lola Michel,* Anna Northcote, Elvira Rone, Christine Rosslyn, Vera Sevna, Edna Tresahar,** Audrey Valeska.

Men:

Anatole Vilzak, Stanley Judson, Paul (Pavel) Petroff, H. Algeranoff and Dimitri Rostoff with Jan Kowsky (Leon Kellaway), Travis Kemp, Slava Toumine, A. Piekers, George Zorich.***

* The name Lisa Mitchell is mentioned in a review (‘Ballets of beauty’, Courier Mail (Brisbane), 15 October 1934, p. 21) but not in cast lists in programs. I have assumed the review is a misspelling of Lola Michel, a name that does appear in cast lists and reviews.

** The Sydney Morning Herald mentions an Edna Tresabel (‘The Russian Ballet. Arrival in Sydney. Olga Spessiva and her company’. The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 1934, p. 12). I have not been able to find another reference to Tresabel and have assumed it to be a misspelling of Edna Tresahar.

***George Zorich spelled his second name Zoritch in his memoirs. It was always Zorich in programs for this company.

The following dancers are listed in various South African newspaper sources but did not appear in Australia in 1934–1935: Vera Nemchinova, Anatole Oboukhoff, L. Kutchurovsky (Katshrovsky), Nicolai Zvereff. Marina Grut also mentions that Nana Gollner and Yvonne Blake performed in South Africa (Selma Jeanne Cohen (ed), International Encylopedia of Dance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), Vol. 5, p. 650.

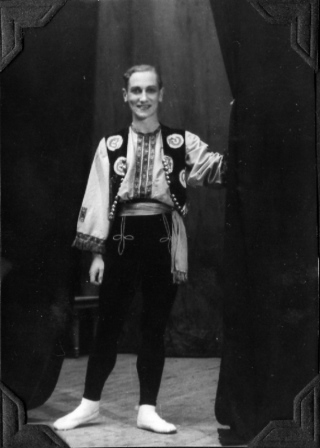

A photo of Otto Kruger appears in Brisbane programs but this name never appears in cast lists in the programs.

***********************************

The material contained in these appendices should not be considered as necessarily complete or definitive at this stage. Any additions or corrections, preferably with sources cited, are welcome. Other online material about the tour is at this tag: Dandré-Levitoff Russian Ballet.

All textual material contained in these appendices and in the article is the intellectual property of The Society for Dance Research and should not be reproduced without permission. Full bibliographic details.

Michelle Potter, 23 September 2013

Featured image: Finale, Les Sylphides, Dandré-Levitoff Russian Ballet, ca. 1934. Personal archive of Anna Northcote, private collection

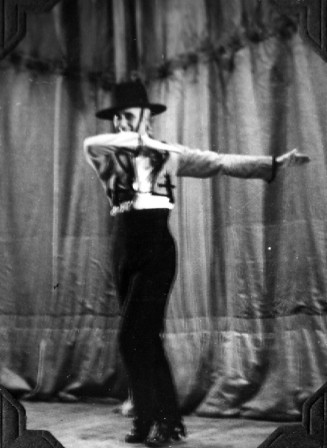

The image below is labelled ‘Lisa … Carnival’ in Anna Northcote’s photo album. It is possibly the Lisa Mitchell/Lola Michel/Lisa Mulchelkans/Elisa Mutschelkmans mentioned in the list of dancers above and in the comment from David Sumray below.