by Jennifer Shennan

Memories from across 40 years of life and work and people at New

Zealand School of Dance were triggered by a recent gathering.

Christine Gunn has

been on the faculty at New Zealand School of Dance as classical ballet tutor

for 40 years. A celebratory gathering took place at Te Whaea, the school’s

venue, in early September to mark the occasion but no-one is taking that as a

signal of her impending retirement. The opening speech of heartfelt thanks by

director Garry Trinder acknowledged that Christine prefers not to play the diva

but just to get on with the work. He quipped how pleased he was to have found

her the perfect fridge magnet which asks ‘Would you like to speak to the person

in charge, or to the person who knows what’s going on?’ Perhaps they’ll let her

retire after another 40 years?

Christine

masterminded the art of timetabling the

curriculum for both the classical and contemporary dance streams—(this is

tantamount to completing Sudoku puzzles while simultaneously playing two Chess

games). It was not merely the timetabling skills being remembered and

celebrated however, but the dedication to teaching consistent, supportive

classical technique and repertoire classes that have guided many a ballet

student towards their performance careers. Raising her own family of two

daughters must have required further skills of time management on many

occasions.

Anne Rowse was

director of the then National School of Ballet when Christine joined the staff

in 1979. With Anne, plus Dawn Sanders as part-time tutor and secretary, that

made a staff of three. How ever did they do it, in those asymmetric studios

that you had to traverse to gain access to the dressing rooms? Well, you’d

never have guessed from the calibre of the repertoire in annual Graduation

seasons in the Opera House that training conditions were anything less than

perfect. It takes hindsight to recognise pioneering of course, but the list of

graduates from New Zealand School of Dance, then and since, includes major

figures in world dance. Piano accompanists were always the best in town and,

over time, other teaching staff were appointed, new premises found, and

resources grew.

Turid Revfeim (who

has recently written the 50 year history of the School, and is now a tutor

there) was a student in the year Christine arrived, and she reminisced on what

was done despite those meagre resources. Turid later joined Royal New Zealand

Ballet as did many other graduates, Dawn had also earlier been a dancer with

them, and such links ensured a genuinely close rapport between the School and

the Company, at that time directed by Harry Haythorne. Students used to turn up

in droves at the theatre each night to meet the stalwart Company Managers,

Warren Douglas or Brendan Meek, themselves both NZSD graduates, for passes to

every performance of the season which those days spanned a fortnight. Standing

room if need be, but students seized every chance to glean inspiration of what

their training was all about, in the context of the theatre. The resulting

artistic harvest was bountiful, but it only grew from old-fashioned common

sense and the best kind of opportunism.

Christine’s choice

at her gathering was for students to perform an excerpt from Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco which they did with a

commendable clarity of line and musical acuity. Luke Cooper, a recent graduate

now dancing with RNZB, had organized video messages to Christine from former

students living and working afar. All the students then performed a massed

Maori tribute, a waiata with the

talisman wiri of quivering arms and

hands that breathes life into dance. The male students delivered a mightily galvanised haka taparahi that could have given the

All Blacks the shivers.

The large

gathering was a spirited one and no doubt evoked many and varied memories among

former teachers and students of their experiences across those 40 years—of

things trained, learned, rehearsed, performed, triumphed, loved, hoped, danced

and dreamed. I’ll put the (injuries and heartbreaks) into parentheses. Nothing

about dance is easy—it’s only meant to look that way, with the grace of divine

nonchalance suggesting that you, the audience, could be dancing too.

*********

Anne Rowse invited me to join the staff in 1982, to tutor in Dance Studies—Renaissance and Baroque repertoire, Dance notation, History & Library studies, World Dance Traditions including Pacific and Asian cultures—all the interesting things no one else wanted to teach. How lucky was I? I also offered public courses of dance interest through the Centre for Continuing Education of Victoria University of Wellington, so there was some creative accounting as Anne agreed to let the School premises be used in exchange for free places for students. Win-Win. I was also entrusted to build up the School’s library from fairly meagre holdings, so it was surely a stroke of luck that Smith’s Bookshop, the town’s very best second-hand bookshop, run by Dick Reynolds, was in an adjacent building, so I could each week sniff out dance and related arts books for bargain prices. One day, to my astonishment I found David Garnett’s Lady into Fox, a short story that had been famously adapted, by Andrée Howard, into a choreography by the same name, and the one ballet I most wished I could have seen. I consider myself quite old, but not quite old enough to have caught it when Ballet Rambert toured here in 1949. You could search the shelves of bookshops worldwide and not find Garnett’s stories, so this was a glint of gold. I recall cancelling that day’s planned class and telling the students all about Lady into Fox instead.

How poignant it

was some years later at a matinee of the School’s graduation, with the front

rows of the stalls at the Opera House filled with audience from an old folks’

home (another of Anne’s initiatives), to sight Dick Reynolds propped up in a

wheel chair, nodding and faintly clapping along as the students rollicked

through The Lancers’ Quadrille, but I

believe he was wiping away tears when Chopin’s music for the Prelude from Les

Sylphides began.

Another standout memory was a visit from the iconoclast dance-maker Mary Fulkerson from Dartington, an important centre for the arts in Devon. Mary brought her eight hour long performance saga, titled Don’t Tell the Prime Minister I’m coming. The first instalments were performed across two evenings in the BlueRoom at the National Art Gallery, when director Luit Beiringa opened those doors for us, but the third and fourth evenings were across a weekend, posing a problem of access to the NAG. There was no budget. (How ever did we do these things on zero budgets? Well, we just did. You could say they were free because they were priceless, which is of course the opposite of worthless). Anne with typical generosity handed over the school keys for the weekend. That gesture remains as memorable as the dance itself, which ended with Fulkerson tossing each of the eight dresses she had worn through the evenings high up into the air, all the while still dancing, singing, and smiling. But wait, only seven dresses ever came back down to earth. The eighth one caught on a high ceiling beam and dislodged a decade’s worth of dust, glinting in the light as it sent a shaft of golden stars down onto our heads. That was 1983 but I can see that glinting still. And no, we didn’t tell the Prime Minister Mary was coming since Muldoon wouldn’t have known what to do with the information, though nowadays you could tell PM. Jacinda Adern, since she is also Minister for the Arts.

The School moved

to new premises in Cable St., the entrance to which sat between adjacent

doorways—one to Cash Convertors, the other to Abundant Life Spiritual Centre,

daily reminders of the spectrum of possibilities in life as well as art. We

tried to ignore the nine months of deafening pile-driving as Te Papa

construction across the road got under way, and just got on with our work.

Patricia Rianne,

one of New Zealand’s most celebrated expatriate dancers, had returned home and

become Head of Classical Studies at the School, a most valued teacher and

mentor to the students. Her Summer’s Day,

to music by Jenny McLeod, and Bliss,

inspired by Katherine Mansfield’s story, were staged by RNZB and the graduates

dancing there found joy in performing them.

George Dorris and

Jack Anderson, leading New York dance writers, walked in the door one day as I

was teaching Baroque dance. I squealed in delight to recognise them, introduced

them to Anne, we both scolded them for not warning us they were coming, so they

returned a year later and gave a wonderful seminar which we also opened to the

public. We surveyed the many titles of the fabled Dance Perspectives, a series of periodicals edited by our mutual

colleague, Selma Jeanne Cohen. No other dance journal can hold a candle to this

series so I was emboldened to beg our National Library to lend us their

complete run from the Stacks. No-one had ever borrowed them because no-one knew

they were there. They do now. What a weekend we were treated to. I can’t

remember if we thanked Anne, but she will have known that the real rewards

survive in the minds and memories of those who attended. The threads that

weave, and the ties that bind.

Ann Hutchinson, leading authority in dance

notation, visited and gave a workshop in which she mounted from her score

Nijinsky’s l’Apres Midi d’un Faune,

to music by Debussy. Nijinsky was the true pioneer of modern choreography, as

well as a legendary dancer. Sad that he is remembered more for his

schizophrenia than his art, but such is the ephemeral nature of dance. The cast

of Faune calls for seven dancers, one

male and six females. As luck would have it, just 14 students turned up, two

males and 12 females, so Ann set about teaching the work to two casts and the

whole piece was completed by the end of the afternoon, which you would have to

rate a small miracle. The mercurial Warren Douglas was there that day and

danced the Faune, as well as many roles at RNZB in following years. Years later

but still young, he died tragically, of complications from Aids. It was so sad

and so wrong to have to write his obituary. We must never forget the dancers

whose lives that cursed illness snatched away. Warren might well have become a

brilliant director of RNZB, and would have changed the world.

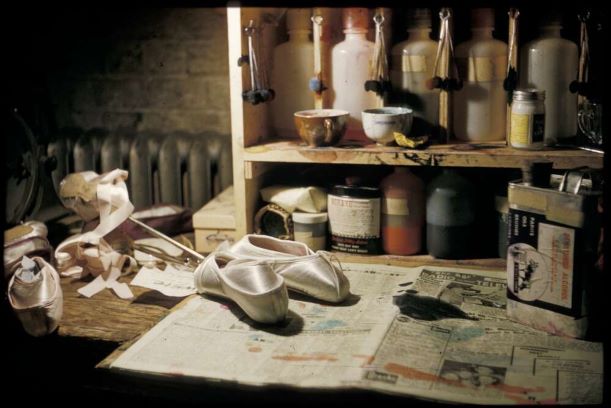

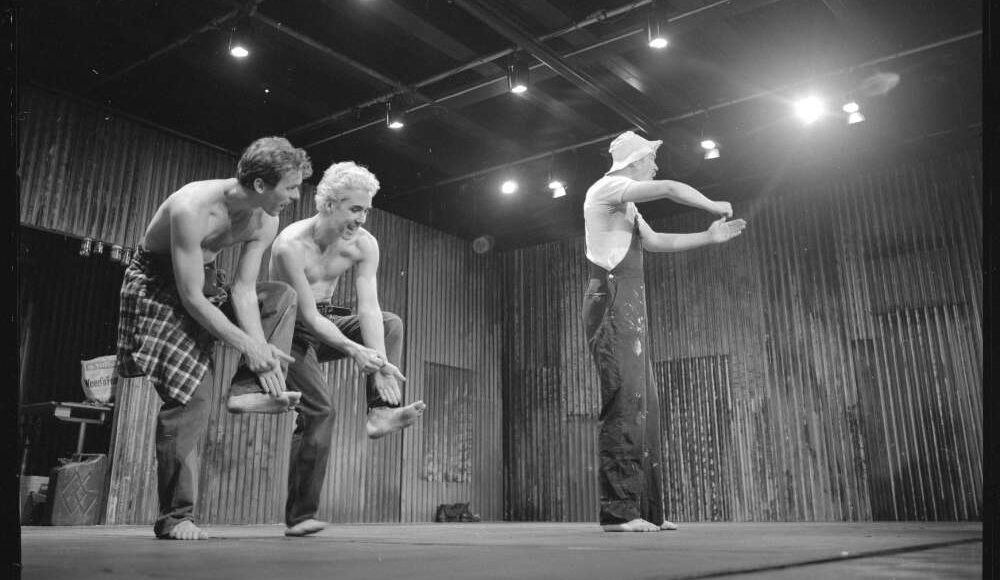

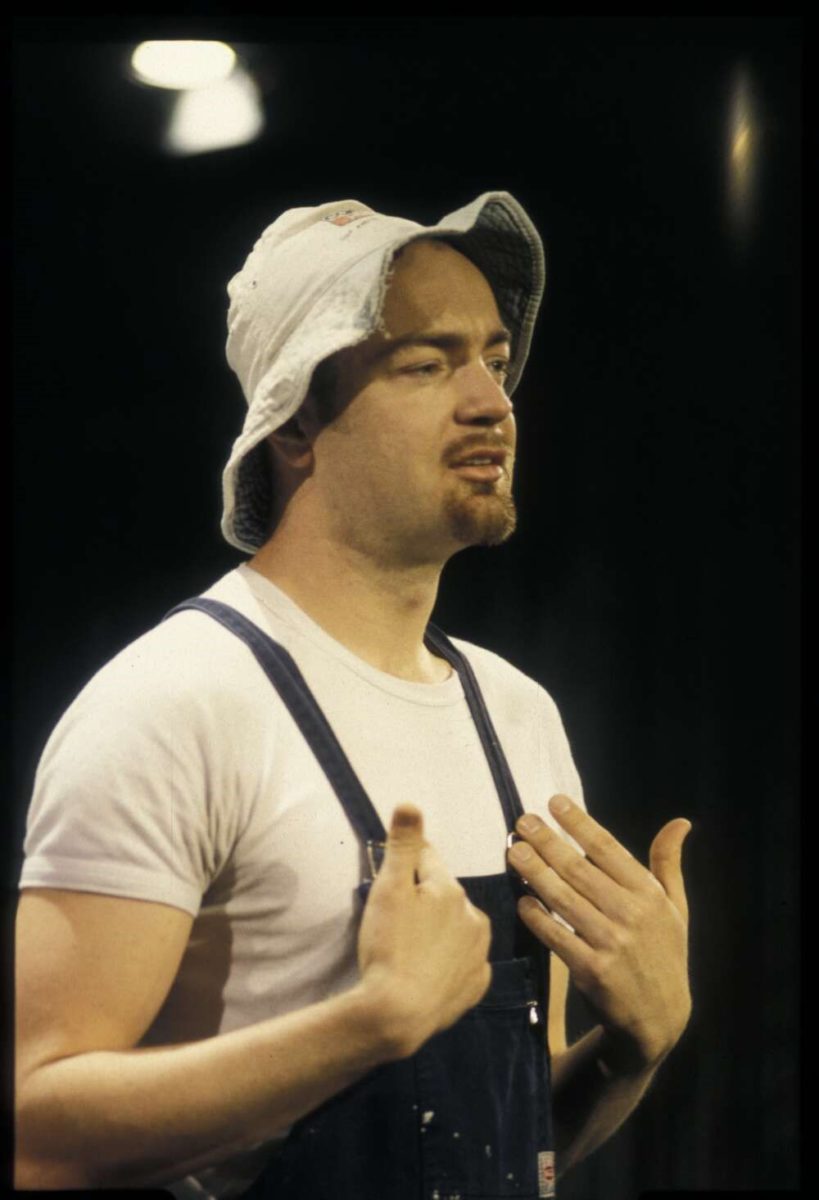

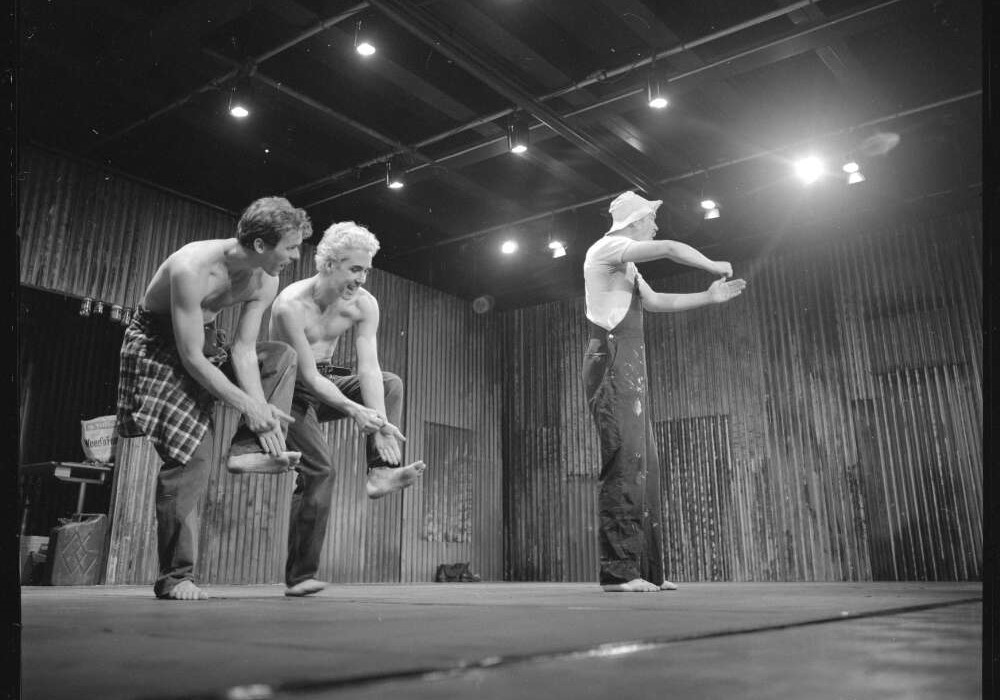

The most treasured

heritage for me throughout my 20 years teaching at the School was undoubtedly the repertoire of

choreographies by Doris Humphrey and José Limon, pioneers of the best of

American modern dance, taught and staged by Louis Solino who had been a member

of their company in New York for years.

It was another of Anne’s courageous moves to appoint Louis to the staff, since

there might have been resistance to the distinctive technique and repertoire,

but he was an unusual and quiet genius and in fact over the years turned up

gold in a repertoire we’d have been lucky to catch in any world capital … Air for the G String, Day on Earth, The Shakers, Two Ecstatic Themes, There is a Time, La Malinche, The Unsung,

Dances for Isadora, Choreographic Offering, The Moor’s Pavane in seminar.

Later the mighty Bach Chaconne was

performed by Louis’ partner, the multi-talented Paul Jenden. Paul has since

died and a broken-hearted Louis returned to the States, but make no mistake,

anyone who ever danced in, or saw rehearsals and performances of those Limon

and Humphrey masterworks will never have forgotten them. Next month’s story

might tell the detail of how that came about.

Everyone present

at Christine’s celebration will have had memories like these, all the same, all

different. The following weekend, large numbers of us gathered at parties

in Paekakariki to help Sir Jon Trimmer

celebrate his 80th birthday, and his 60 years of performing with

RNZB. Jon’s sister, Coral, came from Melbourne with her harmonica in her pocket

and played jazz numbers from the 1920s like a shimmering hummingbird, cavorting

and gliding about, giving total lie to her 89 years. We knew this was her

instrument but hadn’t heard her play. Now we have. That will have to be the next next month’s story.

Between those two

gatherings, our daughter gave birth to her firstborn, a baby girl. I’ll let her

grow a while and then maybe I’ll make for

next next next month, a story about the dance-like movements of a wee,

serious, busy, tiny one as she explores the world around her, learning to latch

on and to change sides, to yawn and to hiccup, to sneeze and to gurgle, to make

frog’s leg kicks that Jeremy Fisher might envy, and, when her arms are

unswaddled, to conduct and wave at symphony orchestras. The baby as dancer—I’m

up to review that.

It was Eugene O’Neill who said, ‘‘There is no present or future—only the past, happening over and over again—now.’ I like that, so think I will help myself to his words.

Jennifer Shennan, 30 September 2019

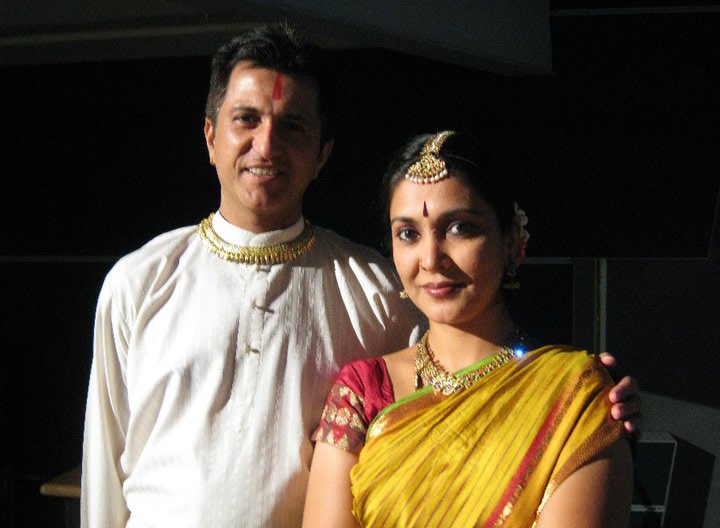

Featured image: Christine Gunn cutting her anniversary cake. New Zealand School of Dance