3 March 2019. Wellington Railway Station Foyer

Choreography: Lucy Marinkovich/Borderline Arts Ensemble

Performers: Hannah Tasker-Poland and Emmanuel Reynaud

Music: Sergei Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No.2 (Adagio)

… after 1945 David Lean /Noel Coward film classic, Brief Encounter.

Reviewed by Jennifer Shennan.

You’ve reached the Wellington Railway Station. In 15 mins your train is due to leave for Waikanae, so there’s time, no great hurry. It’s a fine day, just a bit draughty across the foyer, probably as well to keep your coat on. You stroll around a little and admire the warm pinkish-brown of carrara marble walls, the high vaulted ceiling panels painted in bright lightness. It’s all quite beautiful, must be the finest railway station in the world. The speakers are piping familiar Rachmaninoff, which is somehow comforting in such a transitory space.

Damn, something is caught in your eye and it stings, A man passing tries to help you. Whoa! Who is this? All the longing you’ve always kept inside but never voiced out loud, your secret that you could love someone till the end of time, even if there is no such actual person, or, if there is, you’ll never meet, it’s just a longing that you’ve always lived—perhaps others have it too?—but how would you know because this is not anything you can talk about. That would be unlucky and you might be overheard by strangers. There is no such person, too true to be real, too beautiful to last, to have a name, and she may not even notice you, and you’d risk losing her when you’d only just met. No, he’s just a kind man passing by, trying to help you sort your eye problem. Or let’s say it is just the thing called hope, the thing with feathers, that you nurture in the breast while reading Emily Dickinson’s poems on train journeys.

It’s not that you’re at all the type to fall carelessly and deeply in love with a stranger in a public place—for example, the man sitting in the third row of the No.14 bus that time you went to town … that was a breath-holding ride, you thought you could be together forever … but he knew nothing about you, did not even notice you, so the affair was safely over by the time you alighted at the third-section bus-stop. There was no dance, it was all in your mind, your soft head. So how come this day is different? This man does notice you, more than that—he pauses, he stops, he turns, he offers to help, he wants to meet you, he feels the same as you do. This is a film script, surely? You’re actually in this film, yet you never auditioned, and there was never any rehearsal. Who’s the choreographer here? Swan Lake is the story of a man and a woman who meet, they dance and love, but she is due to fly out that evening and he will lose her forever. This is different, it’s just a train station, remember.

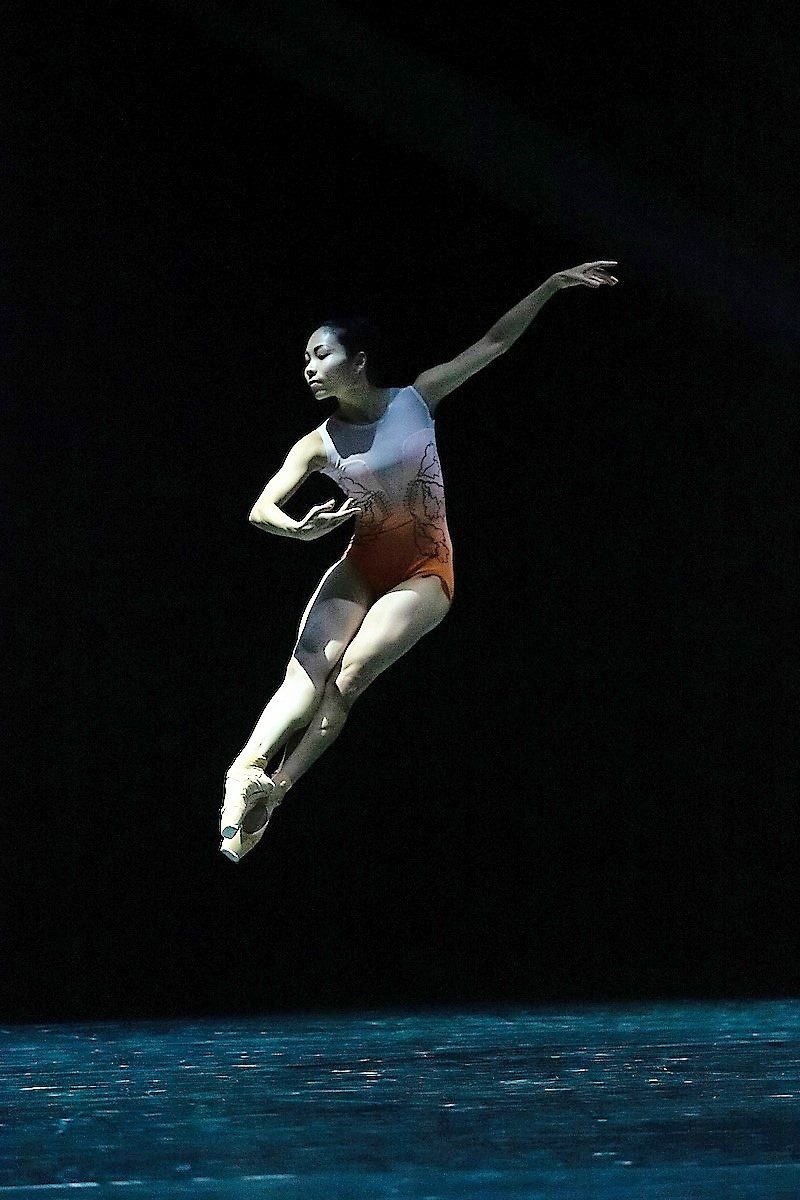

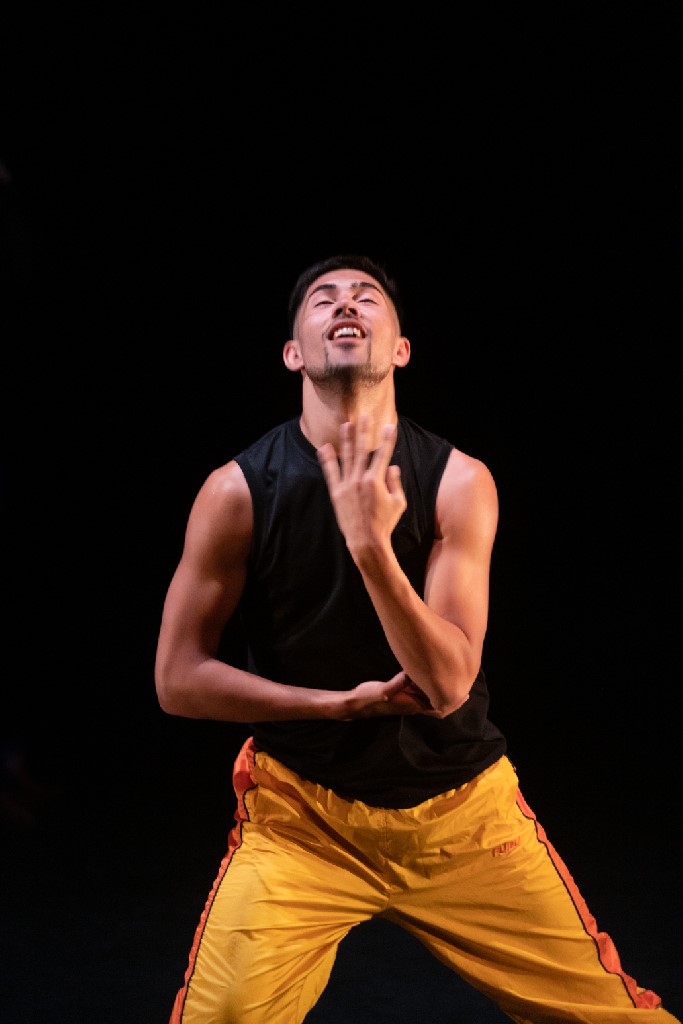

Hannah Tasker-Poland and Emmanuel Reynaud in Lucy

Marinkovich’s Thursday. Borderline Arts Ensemble, 2019. Photo: © Philip Merry

A number of other travellers stop to watch the couple—and are fixed by the beautiful figures-of-eight they see traced, like infinity signs lying sideways. Small fires flicker inside those who are watching too. No one is voicing a commentary, there are no subtitles, no flyers to hand out, no powerpoint. The dance is the point of power. This is not pornography, it’s not erotic (though nearly it is…), it’s just a 13 minute love dance on the marble floor of a railway station, by a man and a woman who keep their coats on while they fall into the depths of each other’s eyes and drown there, just managing to save each other by doing beautiful things, whatever their bodies will allow— like waves and billows, like leaning and longings, with arms, and hands, with legs, feet, faces, eyes, the backs of their heads too—they don’t always need to be watching to know what the other is doing, they can just tell. He knows they will never have to argue or disagree, they will love and hold and be held forever. This is better than all the lyrics of all the love songs on all the shelves of all the music shops of the world. These are minutes of assurance that you can love someone you don’t even know by name, and still catch your train. But, hold the Rachmaninoff … the voice-over announces that the Waikanae train will be leaving in two minutes time. You both pause, you raise hands in the gesture of a farewell wave—oh no—but yes—but no, let it go without you. You walk back towards each other, hold still, hold tight. She has let the train go without her.

All the dance moves up till this point were just rehearsal, so now it’s time to do them all again, only more fully, and slower, deeper to lunge, higher to lift, wider to arc, stronger to clasp. The watching travellers are all choosing to miss their trains too. They can’t walk away from lovemaking. At the start there was a posterboard on the edge of the space that read ‘New World, special coffee & muffin offer free. Today only’ but the message has been changed while no-one was looking and now reads ‘Innocence is contagious, if you like’ which everyone knows is true, and better value than coffee and a muffin, even when that’s free.

They continue dancing and it is the loveliest thing you ever saw in a Railway Station. Then the voice-over for the next train to Waikanae, and oh, she must leave now, and so she does. He turns and walks to the street, it’s his eyes that are stinging now, holding the memory of all that just happened. Probably. Today only. In 13 minutes. And will last forever. Surely.

————-

Lucy and partner/colleague, Lucien Johnson, will take up the year-long Harriet Friedlander Residency in New York. May they keep their coats on. while at the subway station.

Jennifer Shennan, 3 March 2019

Featured image: Hannah Tasker-Poland and Emmanuel Reynaud in Lucy

Marinkovich’s Thursday. Borderline Arts Ensemble, 2019. Photo: © Philip Merry

—