8 August 2019. The Playhouse, Canberra Theatre Centre

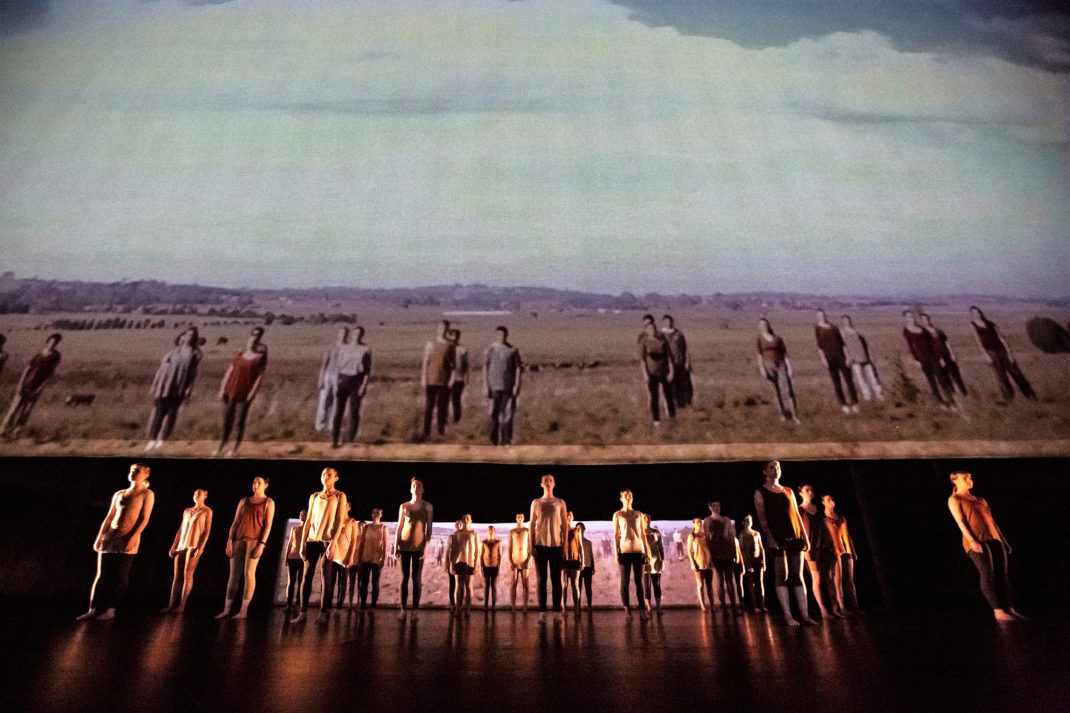

As the curtain went up on QL2’s 2019 Quantum Leap production, Filling the Space, I sat up with a jolt. There were a couple of ballet barres onstage and dancers standing in ballet positions, even doing the occasional demi-plié. Not only were we faced with the barres and the pliés but the entire space of the Playhouse stage was stripped of its usual accoutrements—no legs or borders to mask the wing space or to hide the lighting or flies. Everything that is usually hidden from the audience was on show. What was this? Well, it was the beginning of James Batchelor’s Proscenium and Batchelor, now with a good number of works behind him, has never left us in any doubt that what he creates will be unusual in approach and leave us to ponder on what his works are about.

But what made Filling the Space, the overall production, so fascinating was that it showed off the diversity of the choreographic voice. We saw the work of three choreographers, Batchelor, Ruth Osborne and Eliza Sanders, and it would be hard to find three works so different in conception and vocabulary.

Batchelor’s Proscenium examines the space of the stage both within and beyond the structure that frames that space—the proscenium. It was rewarding to consider the particular use of the space he identified in the context of dance and architecture, which was the overarching theme of Filling the Space. But for me Batchelor’s use of the architecture of the stage space was not the most interesting feature of his work. His choice of movement vocabulary was the highlight. It ranged from extremely slow and intensely detailed, even introspective, movement to faster unison work with some partnering that relied on balance and support. As well there was extensive manipulation of those barres and other metal frames, some that dropped from the flies, others that looked like clothing or costume racks. At one point we watched a circus-like stunt with one dancer balancing on a narrow support joining the end parts of one of those racks while another dancer spun the whole structure with ever increasing speed in a giant circle. At another point, rows of chairs were brought onstage and dancers entered, sat down, moved some parts of the body, then rose and, with arms still in the pose they had taken while seated, made their exit. Batchelor was examining how stage space can be filled and emptied in various ways, but it was the way in which that examination occurred that was more interesting than the fact that it occurred.

Ruth Osborne’s Naturally Man-Made was danced against a background of footage shot on and around the grand staircase of Canberra’s Nishi building, a staircase made of recycled timber and a spectacular part of the building. Sometimes we saw the staircase as an installation devoid of people, at other times the footage included dancers performing on the staircase. In front of this footage dancers performed what might be called Osborne’s signature style—mass groupings of dancers with occasional break away moments. It fulfilled nicely, if in an obvious manner, the concept of dance and architecture.

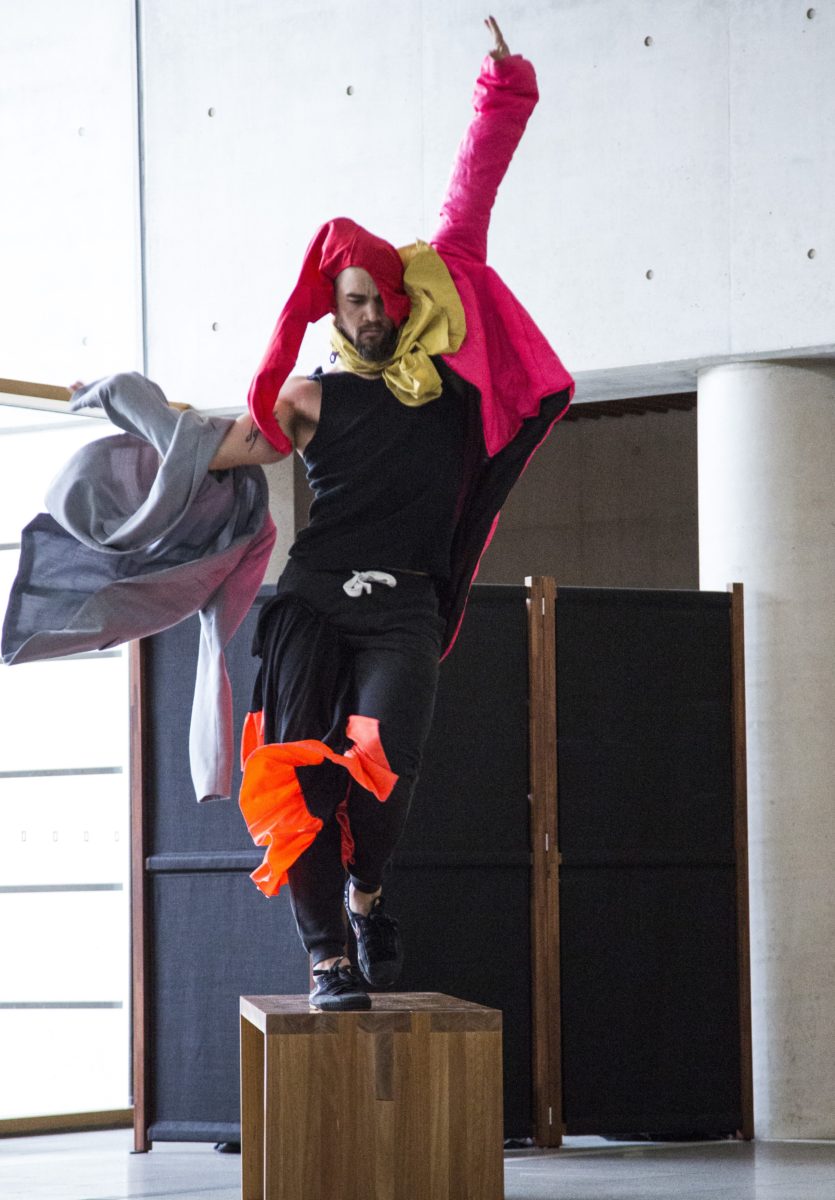

Eliza Sanders had a totally different take on what constitutes architecture. Her work, The Shape of Empty Space, looked at emotional responses to different spatial environments. In this work her movement vocabulary was almost like mime. It focused on two main emotions, a feeling of being wild and free in some environments, with an accompanying flinging of arms, legs, and indeed the whole body in an unrestrained way; and a feeling of being crowded into a tight space, with an accompanying restraint in movement and groupings of dancers. The work was stunningly lit by Mark Dyson with well lit spaces alternating with hidden spaces set up by black curtains hanging at intervals in the performing space. It was architecture built by light and darkness through which we watched dancers appear and disappear. The work had a sculptural ending as dancers built an architecture of their own.

Both Batchelor and Sanders are QL2 alumni who are now working professionally as independent dancers and choreographers. Osborne is an early mentor to them. How lucky are the current dancers of QL2 that they get to work with choreographers whose creativity is so different, whose vocabulary is so individualistic, and whose work is so fascinating to watch, and so interesting to think about.

Michelle Potter, 10 August 2019

Featured image: Dancers of QL2 in James Batchelor’s Proscenium. Quantum Leap 2019. Photo: © Lorna Sim