My review of Swan Lake from Victorian State Ballet was published online on 5 April 2025 by CBR CityNews. Read it at this link. Below is a slightly enlarged version of the review.

************************

4 April 2025. Canberra Theatre

The dance world has seen a wealth of versions of the ballet Swan Lake since its first performance in Moscow in 1877. Many choreographers have taken up the story of Odette, the Swan Queen, and the supporting characters, including of course Prince Siegfried, whose activities have impacted her life. Some choreographers have made changes to the storyline and created new, highly personalised choreography for their creations. Others have attempted to recreate the original work, as far as that is possible.

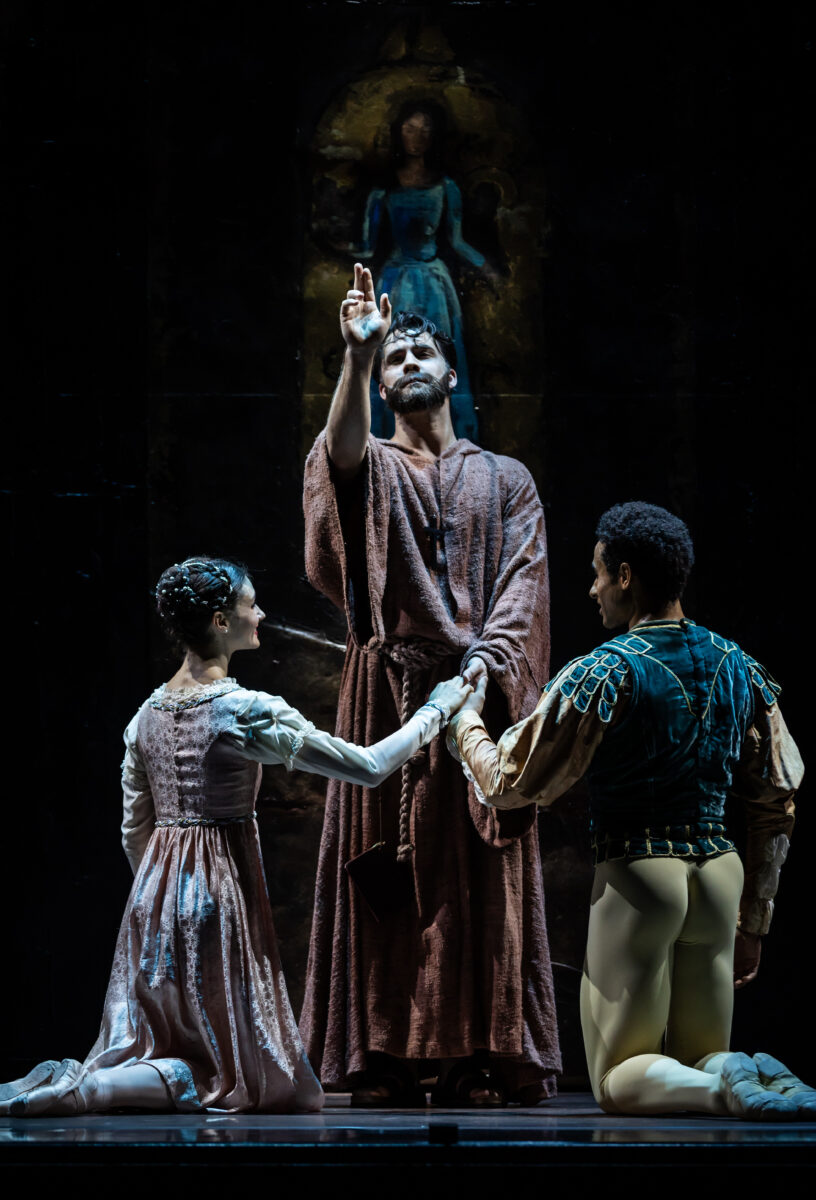

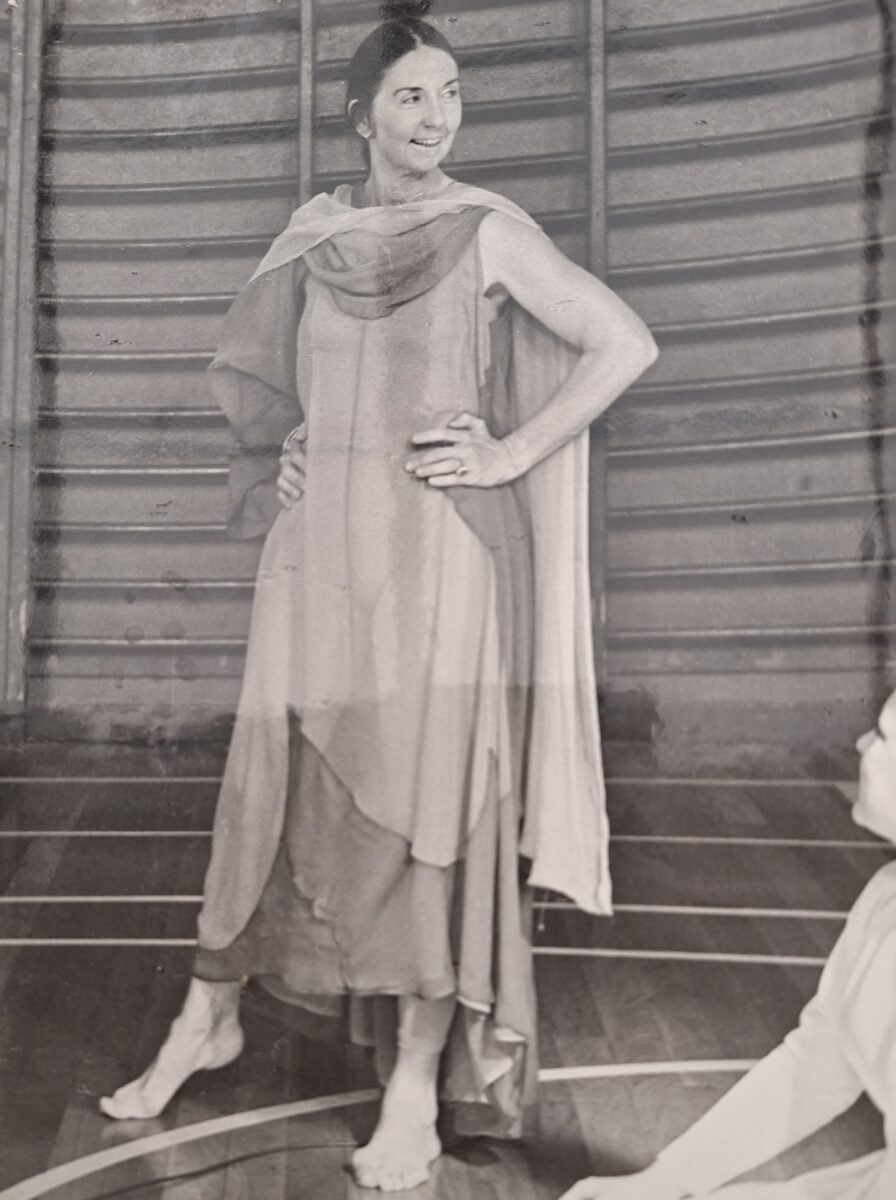

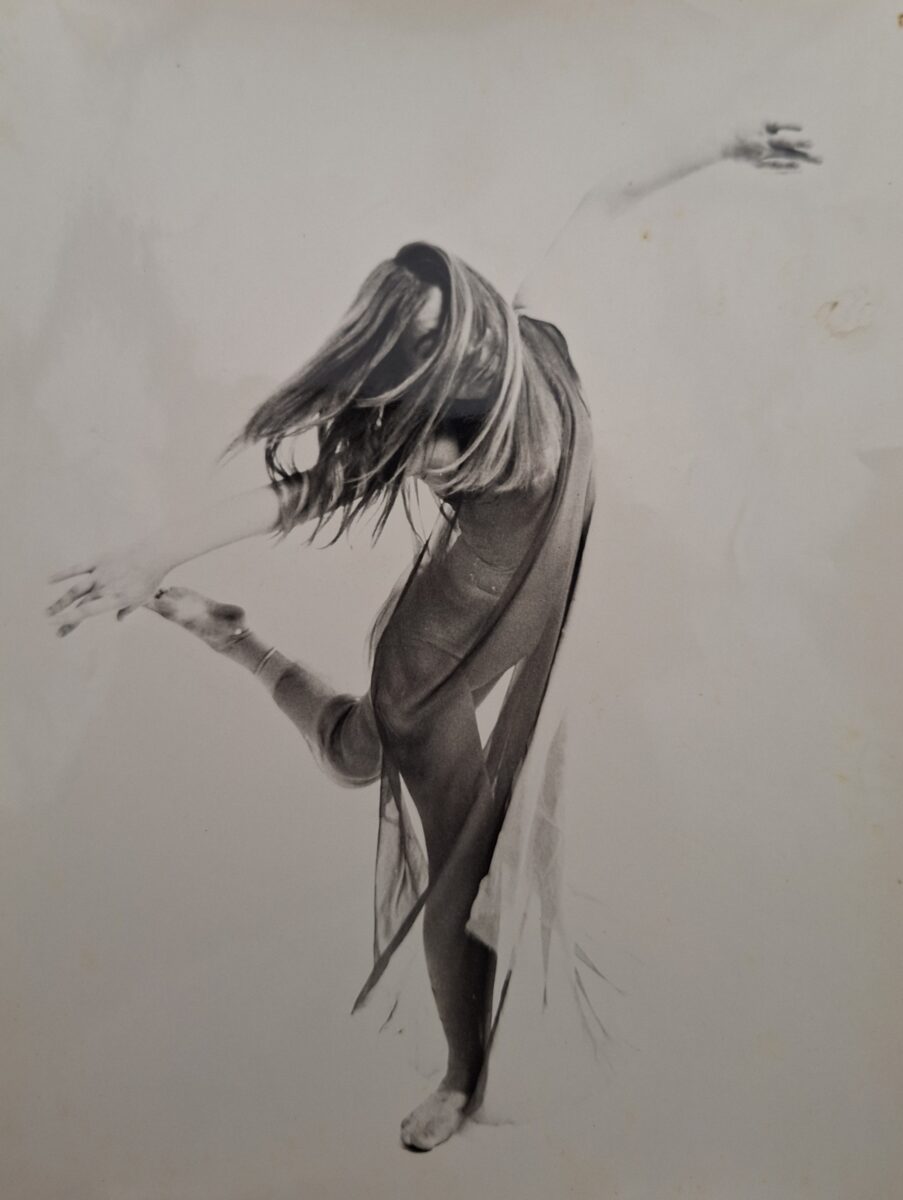

The production presented by Victorian State Ballet was choreographed and co-directed by Michelle Sierra. It followed to a large extent the traditional narrative of Odette, who has been turned into a swan by the evil von Rothbart. Her return to human form is only possible by a declaration of love from a human being.

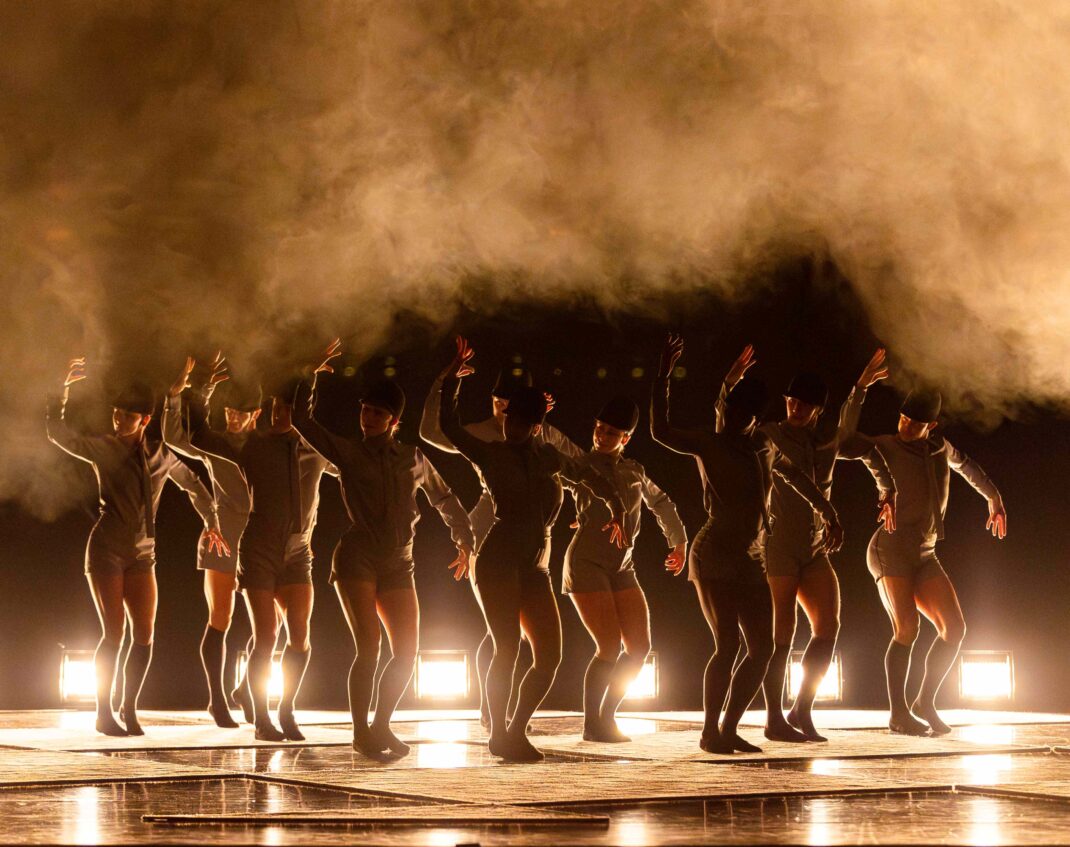

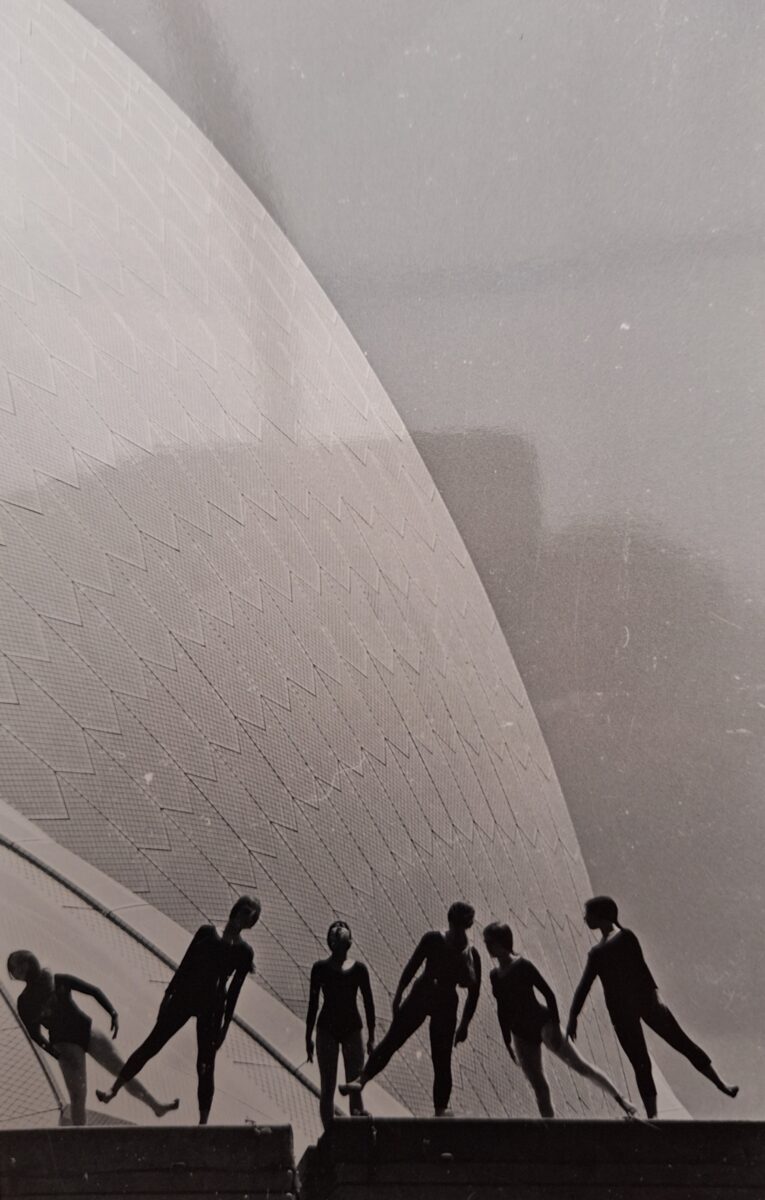

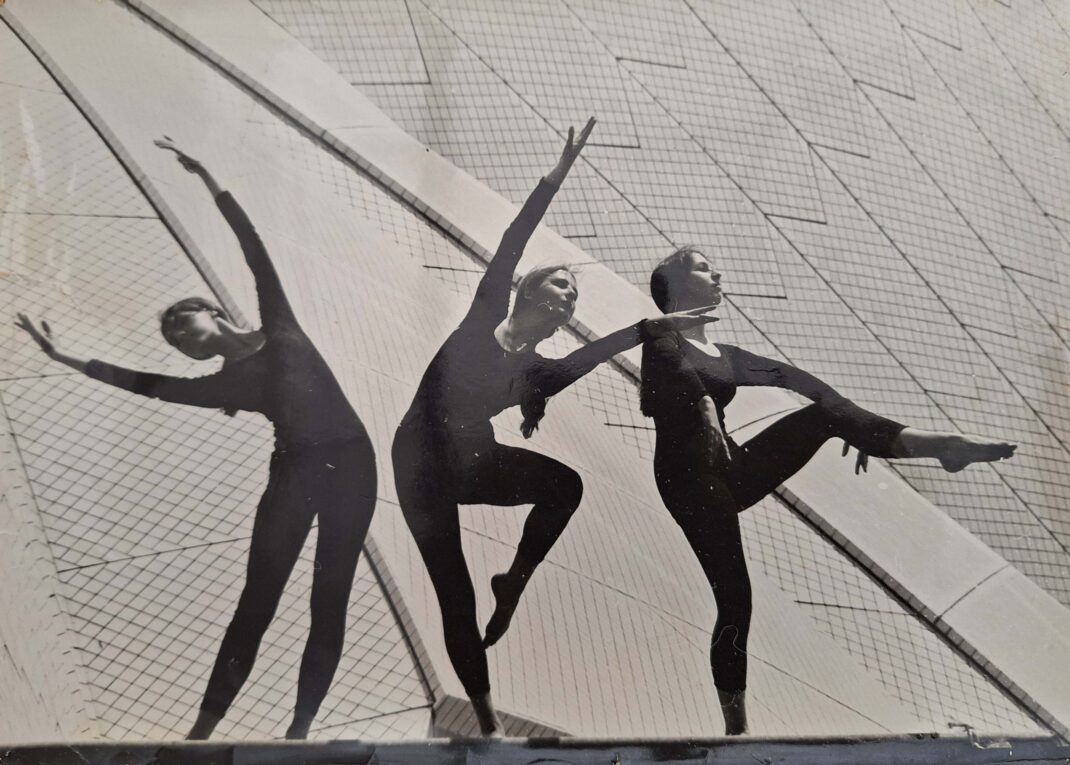

We saw most of the familiar and most celebrated aspects of the traditional story: in Act 1 the birthday celebrations of Prince Siegfried; the dance of the four little swans in Act II; the thirty-two fouettés from Odile (who is impersonating Odette) in Act III; the character dances from across the world, also in Act III; the several pas de deux between the Prince and the Swan Queen across the work; and the impressive groupings of swans in Acts II and IV.

But there is an astonishing ending to the final act of Victorian State Ballet’s production. The finale to Swan Lake has seen various changes over the years, but I have never seen anything like the ending devised by Michelle Sierra.

In Act II, Siegfried, while out hunting following his birthday celebrations, has fallen in love with Odette, the leader of a group of swans. But in Act III, at a ball in his palace, he is deceived by declaring his love for an uninvited guest, Odile, having been persuaded with the help of von Rothbart (disguised as a magician) that she is Odette.

In Act IV Siegfried returns to the lakeside where he first encountered Odette. Both are in despair over what has happened and declare their love for each other. This declaration destroys the curse of von Rothbart who dies dramatically onstage. But even more dramatic is the return to human form by Odette and the totally unexpected transformation of Siegfried into a swan. He has taken his place in the flock of swans from which Odette has been saved. A staggering change to the story!

Some other noticeable changes were choreographic. I especially enjoyed the character dances in Act III which had a stronger than usual balletic component to them. I was also impressed by the way in which von Rothbart, danced by Tristan Gross, appeared to have a greater role in the work than is usual. He often only appears briefly and is sometimes only seen from a distance. In this production he interacted closely with the swans, including Odette, in Act II and there was no doubt as to his importance. But I wish his acting had been a little more dramatic. Perhaps his costume and make-up needed to be a little more impressive? His evil character just didn’t seem clear or strong enough.

The dual role of Odette/Odile was well danced by Elise Jacques and that of Siegfried by Benjamin Harris. Especially strong performances also came from the two leading swans, Maggie de Koning and Alexia Simpson, who worked well together given their similar performing style and that they were of a similar height.

My big gripe, however, concerns the overall technical standard of the dancing. The dancers in this company use their arms, and upper body in general, with beautiful fluidity and sense of shape. But I so wish they (and I mean all of them including the principals) put the same effort into their feet. Well pointed feet make a huge difference to the quality of ballet dancing and poor use of the feet prevented this Swan Lake from being as strong as it might have been.

Michelle Potter, 5 April 2025

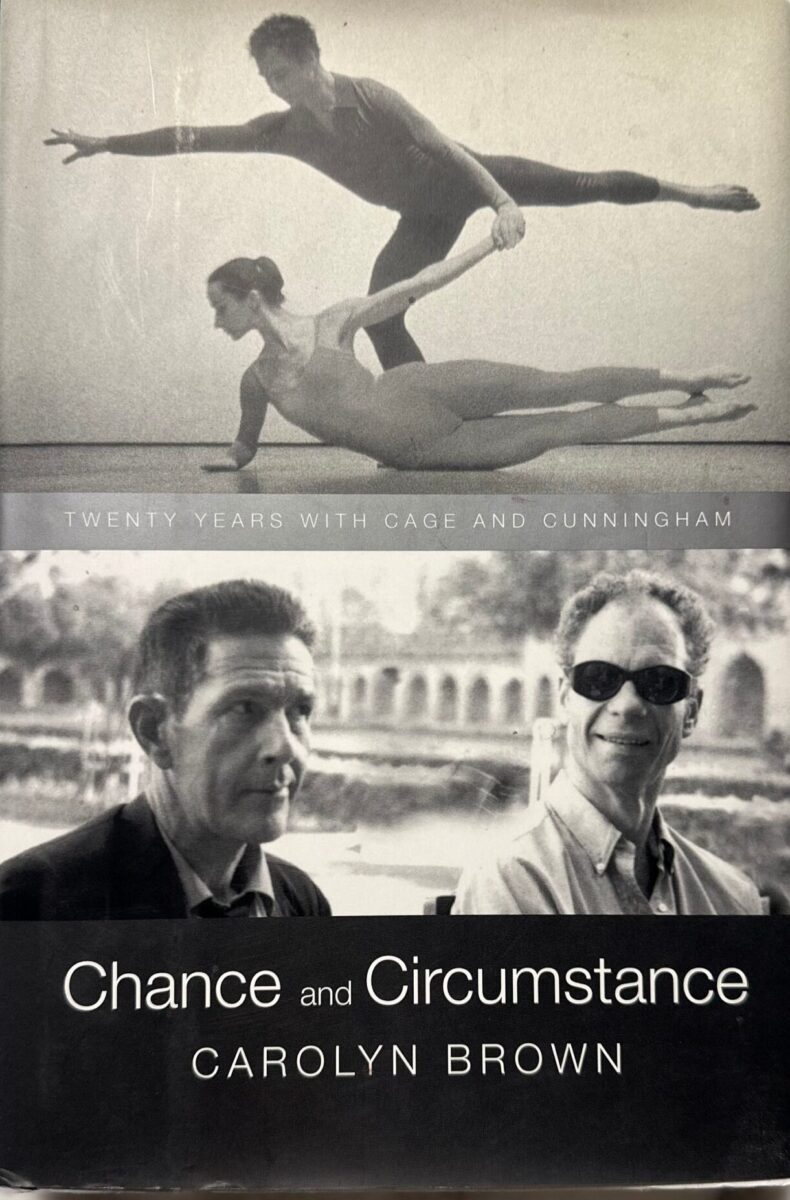

Featured image: Scene from Swan Lake. Victorian State Ballet, 2025. Photo: © Ashley Lean