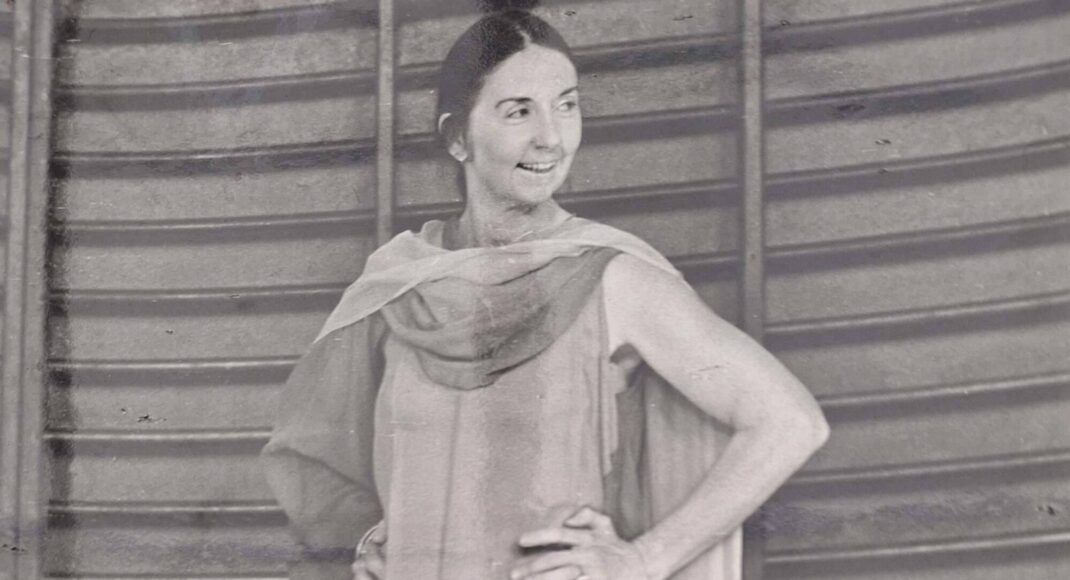

- Norton Owen. Director of Preservation, Jacob’s Pillow

Norton Owen is Director of Preservation at Jacob’s Pillow, an exceptional centre for dance that includes a school and a performance space in Becket, Massachusetts, in the beautiful mountainous region of the Berkshires. Norton has been awarded the 2025 Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award. It is in celebration of his 50th year of being on the staff of Jacob’s Pillow and carries a cash award of $25,000, to be used however the awardee wishes. It also includes a custom-designed glass sculpture by Berkshire-based artist Tom Patti. The award is financed by an ongoing annual gift from an anonymous donor.

I have great memories of Norton and his work, including the ‘Pillow Talk’ I did with Gideon Obarzanek at Jacob’s Pillow way back in 2007. The invitation for me to participate came from Norton and since then I have enjoyed following the work he does. In particular I love receiving the monthly playlist of excerpts from footage preserved at Jacob’s Pillow, which reflects the works that have been presented over the years at the Pillow.

From the March 2025 playlist, whose title is ‘Ailey Connections’, I especially enjoyed Pas de Duke, created originally for Judith Jamison and Mikhail Baryshnikov by Alvin Ailey in 1976 to ‘Old Man Blues’ by Duke Ellington. The footage of Pas de Duke on the March 2025 playlist is from a 2024 presentation, performed on that occasion by two alumni of Jacob’s Pillow school—Jacquelin Harris and Patrick Coker. Watch the 2024 Pas de Duke here.

But the playlist is but one aspect of a wider online platform for which Norton is responsible—Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive. It can by accessed at this link.

Norton’s award is so well-deserved. He is an exceptional curator of dance matters.

- Recent reading

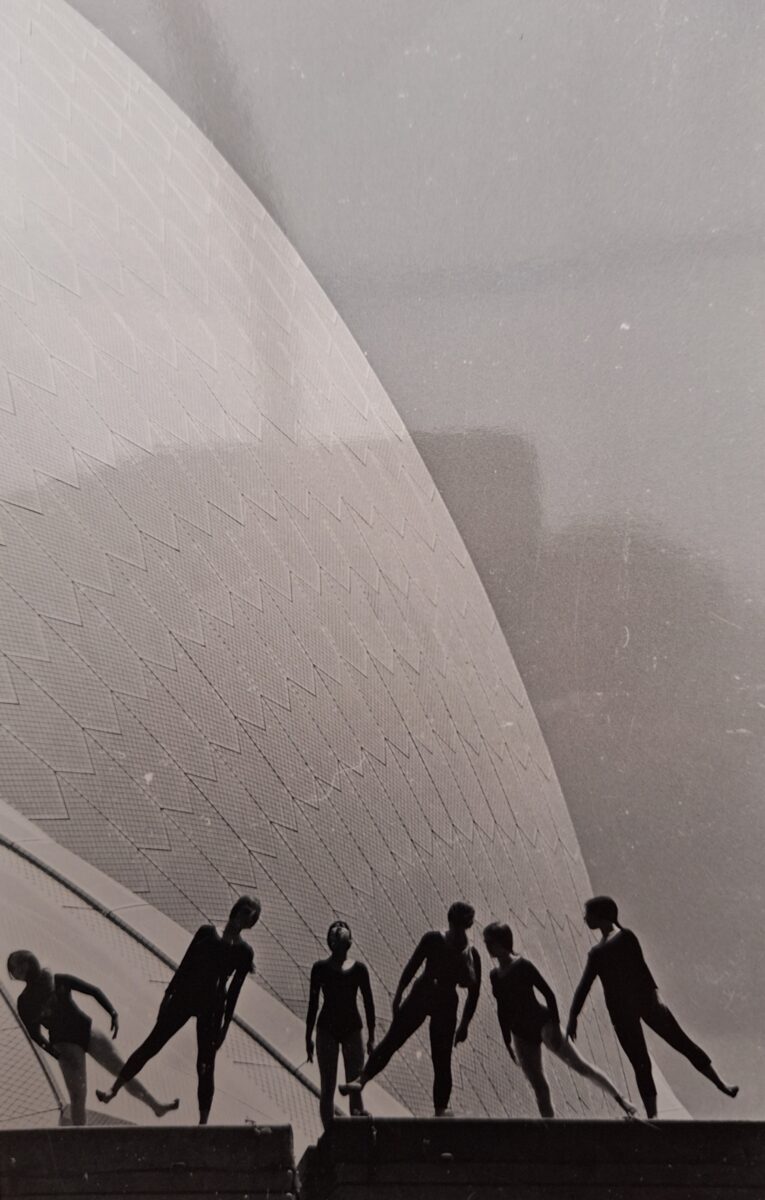

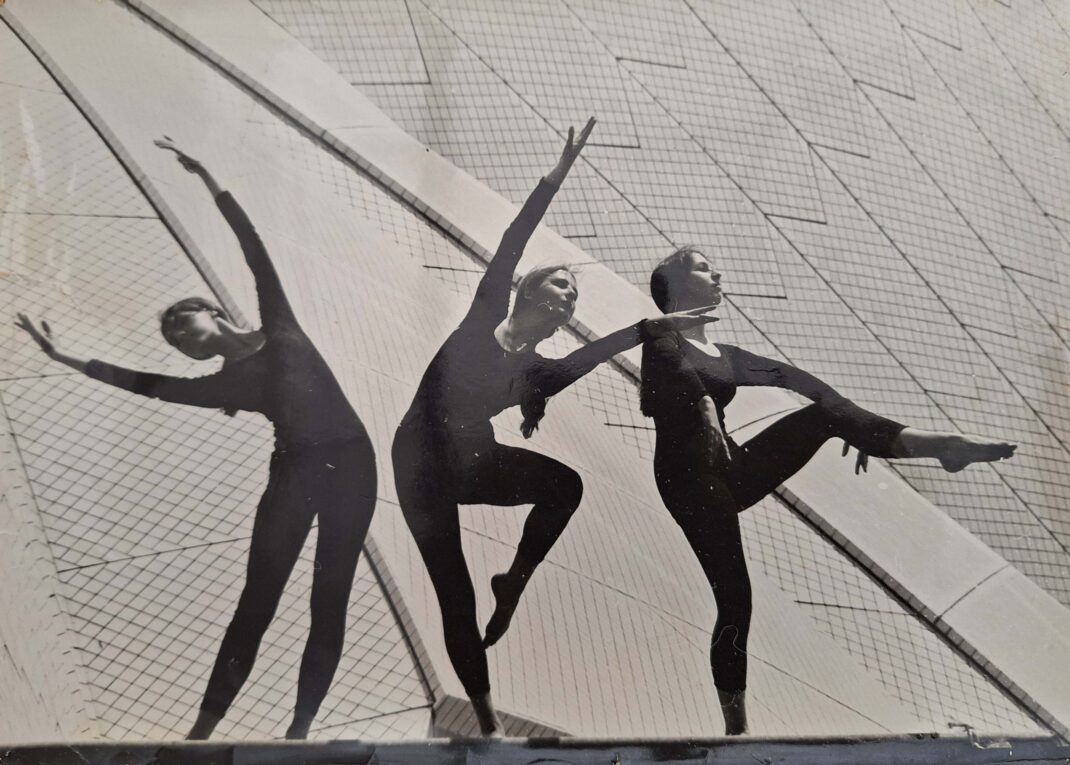

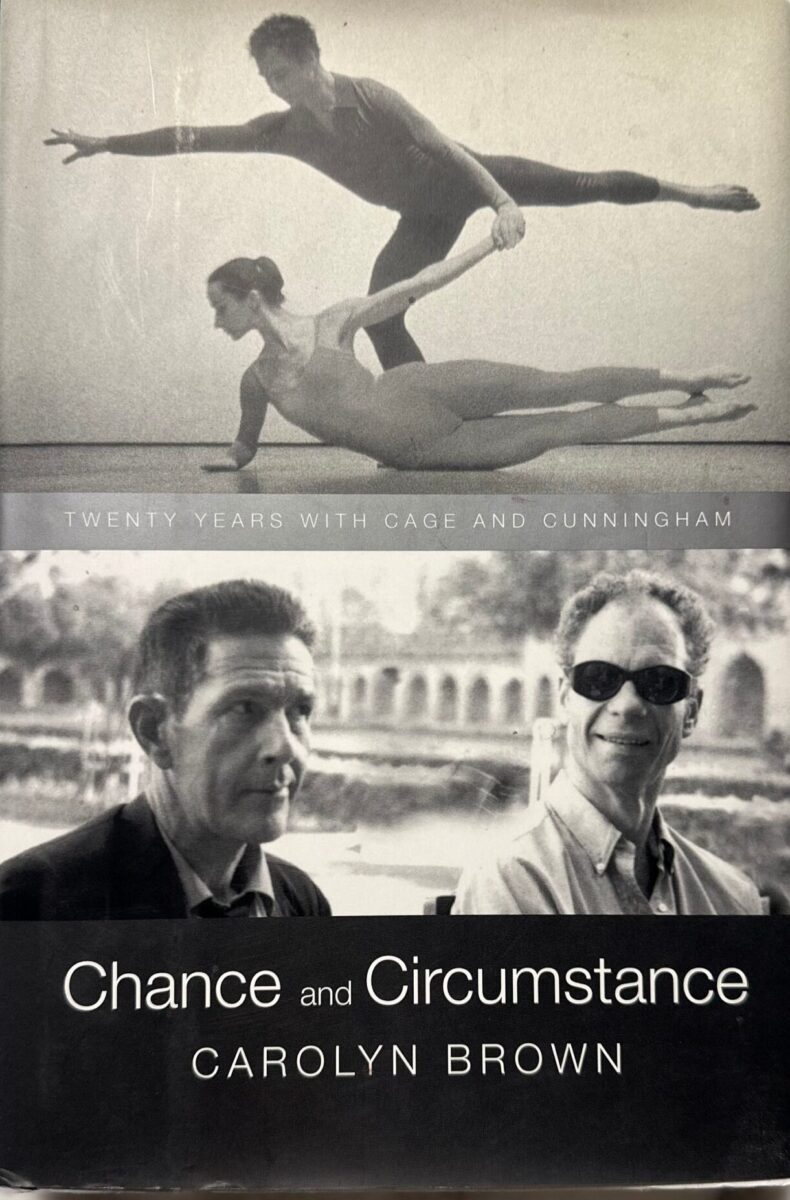

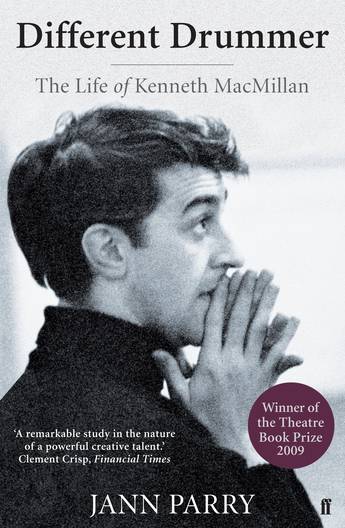

Again from my collection of dance books that either I didn’t get around to reading when I first acquired them, or that have generated new interest for one reason or another, I have just finished reading Carolyn Brown’s autobiography, Chance and Circumstance. Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham, and am in the middle of Jann Parry’s biography of Kenneth MacMillan, Different Drummer. The Life of Kenneth MacMillan.

Chance and Circumstance is surprising in its honest account of Brown’s attitude to her career and contains many, many insights into the personalities with whom she worked. Different Drummer is no hagiography! Parry gives a startling account of MacMillan’s mental issues, his alcoholism, and his bouts of anxiety, all of which explain to a certain extent the nature of the subjects he chose for his works. Both are well worth reading.

- Some statistics for ‘on dancing’

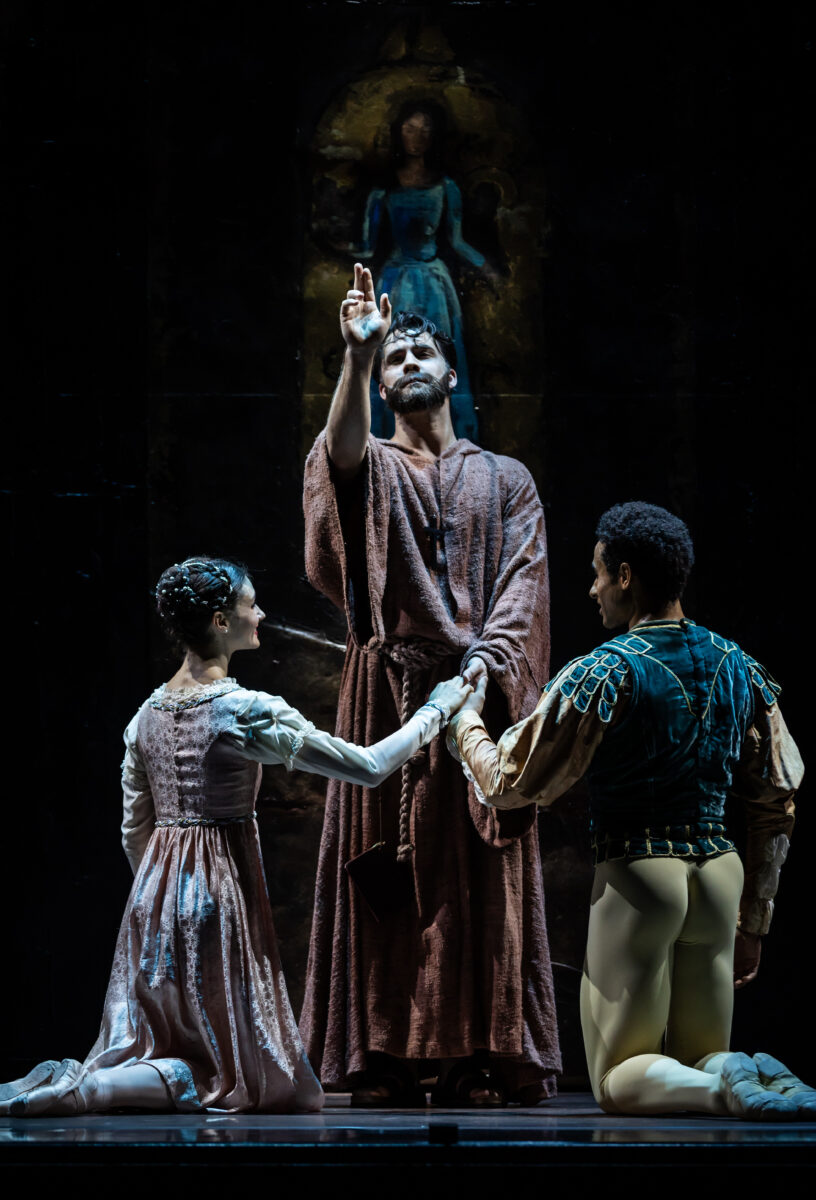

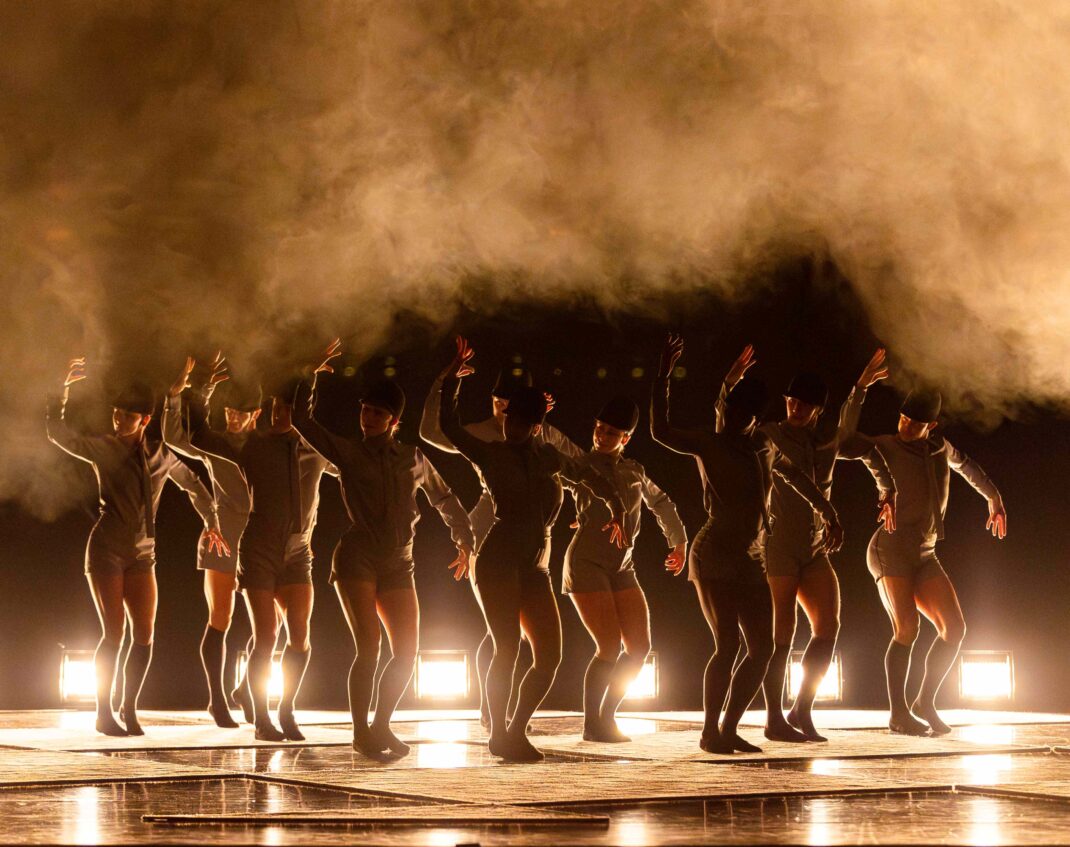

I am always interested to read, via Google Analytics, which posts on this website are the most popular and which cities login to the site most frequently. In the last week of March, Sydney, London, Brisbane, Melbourne, and Wellington were the top five cities (in numerical order). Everything changes of course, even from day to day, and popularity reflects the timing of posts in most cases. In the last week in March, the top five posts in order were ‘RNZB with Scottish Ballet’; ‘Romeo and Juliet. Queensland Ballet’; ‘Essor. Yolanda Lowatta’; and ‘Choros (I dance). Coralie Hinkley’.

I am sometimes curious when an older post pops up and, just recently, my obituary for philanthropist, Anne Bass, published in April 2020, kept appearing on the top ten list. I did a bit of research and discovered that her apartment on 5th Ave, New York, had been sold in January 2025. Clearly there had been interest in what had appeared online about her. And, as a matter of particular interest, her beautiful statue by Degas, ‘Little dancer aged fourteen’, sold separately two years earlier for a record price of $41.6 million.

I continue to think of her often. My 2020 obituary is at this link,

Michelle Potter, 31 March 2025

Featured image: Norton Owen at Blake’s Barn, Jacob’s Pillow. Photo: © Bill Wright