This month’s diary is something of a celebration of three of Australia’s senior artists: Eileen Kramer (Cramer), former Bodenwieser dancer; Dame Margaret Scott, founding director of the Australian Ballet School; and Elizabeth Cameron Dalman, founder of Australian Dance Theatre. Each has been in the news in different ways recently. I have arranged these mini posts, which are largely in the form of links, according to descending order of age of those three dancers, beginning with Eileen Kramer, who will very shortly celebrate her 100th birthday.

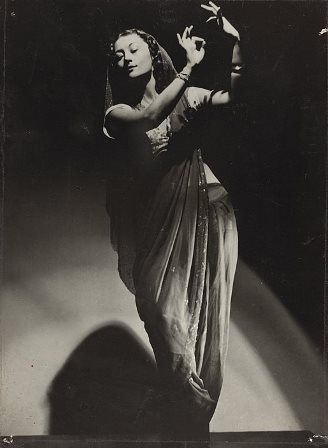

- Eileen Kramer

Early in October I received an unexpected email from a producer for Sydney not-for-profit radio station FBi Radio. The message was to let me know that Eileen Kramer, whom I had interviewed for the National Library of Australia’s oral history program in 2003, was appearing on an FBi Radio program called Out of the Box. She was to appear on the program with singer/songwriter Lacey Cole who had made a music video in which he sang his composition, Nephilim’s Lament, accompanied by Kramer dancing on a rocky promontory above Clovelly beach in Sydney. Here is a link to the radio interview, which was conducted by Ash Berdebes, and a link to the five minute video. [Update August 2016: the link to the radio interview is no longer available]

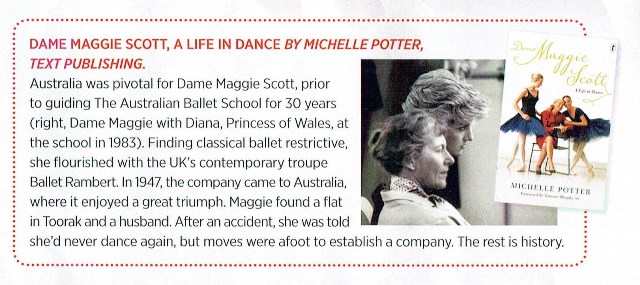

- Dame Maggie Scott: A Life in Dance

I have updated the post on my biography of Maggie Scott with links to recent media stories in which the book is discussed. Here is a link to the updated page.

- Elizabeth Dalman

It is a pleasure to be able to report that Elizabeth Cameron Dalman has been short-listed as a finalist for the ACT Senior Australian of the Year (2015). It is rare for a someone working in the dance area to be nominated in awards of this nature so congratulations to Elizabeth for once again putting dance at the forefront of public life. Dalman is one of four finalists in this category and the ACT Senior Australian of the Year will be announced on 3 November.

- Press for October 2014 [Online links to press articles in The Canberra Times prior to 2015 are no longer available]

‘Wayward daughter delights.’ Preview of West Australian Ballet’s La fille mal gardée. The Canberra Times, Panorama, 4 October 2014, p. 15.

‘A Dame called Maggie.’ The Canberra Times, Panorama, 25 October 2014, pp. 10–11.

Michelle Potter, 31 October 2014