I finally managed to see the recording of Graeme Murphy’s Romeo and Juliet made by the SBS subscription channel Stvdio and recorded on 21 September 2011 at a live performance in Melbourne. Posts relating to this work continue to attract visitors to this site and it was interesting to notice that the number of visitors accessing the site from Adelaide rose dramatically when the work was shown there recently. Adelaide visits continue to remain high and the Romeo and Juliet posts continue to be the most accessed posts overall. Whatever opinions of the work might be out there, there is little doubt that it has inspired incredible interest amongst the dance community.

I was especially pleased to have the opportunity of watching the ballet close up through the Stvdio recording and also to have the opportunity to rewind certain sections that were especially powerful, or that attracted me for a particular reason.

It was rewarding, for example, to be able to watch several times Madeleine Eastoe’s stunning entrance into her bedroom early on in the work. There she is running on pointe so fast that her feet start to look blurred. And those lovely over-the-head claps as she jumps in the air, and those little piqué steps backwards, create such joyous, light as a feather dancing.

The recording made judicious use of a small number of close ups in this early section, which highlighted Elizabeth Hill’s beautiful portrayal of Juliet’s nurse. Hill watches her charge with such a caring look as Juliet tries her ball gown against her young and blossoming figure, and the rapport between them is clearly shown on their faces. Then eventually, off Juliet runs again, jumping onto a chair that happens to be in her way before she springs onto her bed. It’s wonderful choreography and wonderful acting and an absolute delight to watch again.

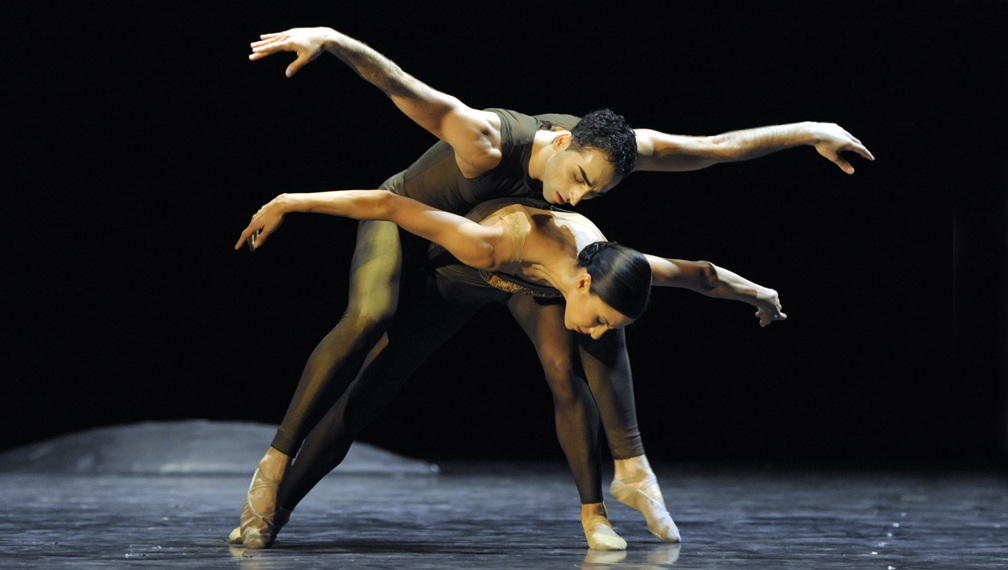

I also loved the serenity of the wedding scene and watching the Murphy touches unfold: the journey to the site of the wedding with Juliet walking across the shoulders of a group of black clad holy men; the duet with the monk that uses the feet as a point of contact between the two; and the playful role the train of Juliet’s wedding dress plays in her duet with Romeo during the ceremony. Murphy’s signature is there in full force!

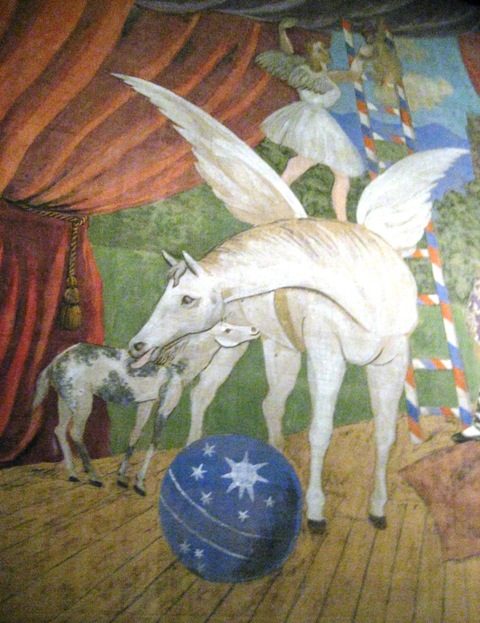

In addition, I really took pleasure watching Adam Bull as Death and still think this role is one of the strong points of the production. Not only does the role act as a powerful through-line, it also acts as an element of dramatic irony. We know what is going to happen right from the beginning when Death picks up a bunch of lilies, a symbol of both purity and death and a recurring motif throughout the work, from the ground in the piazza as the piece opens.

But the scene I thought had the most dramatic power was Juliet’s visit the monk to seek a solution when it seemed that marriage to Paris was her ultimate fate. Murphy makes this a much more significant scene in the ballet than did Cranko in the version that we have been watching in Australia since the 1970s. In the Murphy production the story is told with choreographic and force and through powerful gestures, and we see Murphy using another of his signatures: Juliet is transported through to the country of the holy man held aloft by several black clad figures who carry her through the air in a display of expansive soaring movements.

The conclusion to this scene occurs when Death enters Juliet’s bedroom and stands behind her to slip on her nightdress, and also in the following, shuddering trio when Death places himself between Juliet and Romeo. Again we know there is no hope.

On a less positive note, the final desert scene is not my favourite part of the ballet and a close up look did nothing to make it look better. As one comment has indicated on the original post, Lady Capulet did look decidedly out of place in her high fashion gear, as beautiful as it was, stumbling around with high heels in hand.

In general, though, I thought this recording was beautifully and sensitively made. The more I look at this Romeo and Juliet the more interesting it becomes and the more I wonder about the difficulty we face with the ‘shock of the new’ when we watch a new dance production, in all its fleeting beauty, for the first time.

Michelle Potter, 24 June 2012

Here are links to the first post, and the second.