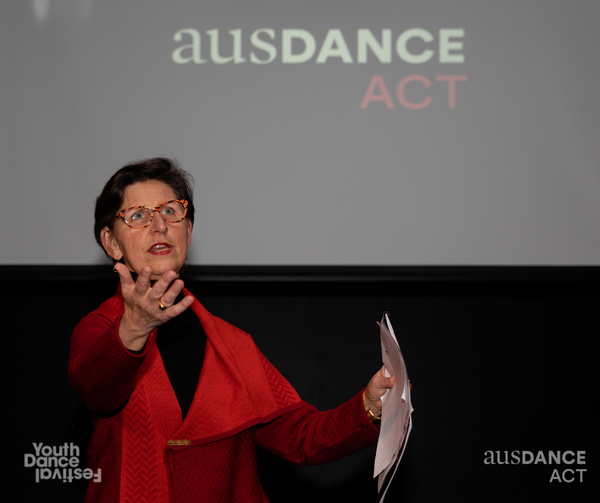

- Lauren Honcope

I was sorry to miss a recent farewell event for Lauren Honcope, who retired last year, 2021, as President of Ausdance ACT. Honcope joined the Ausdance ACT board in 2009 and became president in 2011.

In addition to her tireless work for Ausdance, including seeing the organisation through some difficult times as far as funding was concerned, Honcope has been one of Canberra’s strongest advocates for dance in the ACT. She has served on the boards of the Canberra Theatre Trust; of Canberra’s first professional dance company, Human Veins Dance Theatre, led by Don Asker; and, perhaps most memorably from that time before her work with Ausdance, of the Meryl Tankard Company. It was, in fact, Honcope who persuaded Tankard to come to Canberra for an interview to take over from Asker after he decided to leave Human Veins to take up a Churchill Fellowship.

As a practising lawyer, Honcope brought strong, professional leadership skills to all her theatrical activities. She was admired by all who had contact with her, and another Canberra resident who was unable to be present at the farewell wrote of her work for Ausdance: ‘She was always generous with her time and wisdom to support the arts, and a true advocate.’

I wish her well as she moves into new endeavours, to which I am sure she will continue to bring that same professionalism and generosity.

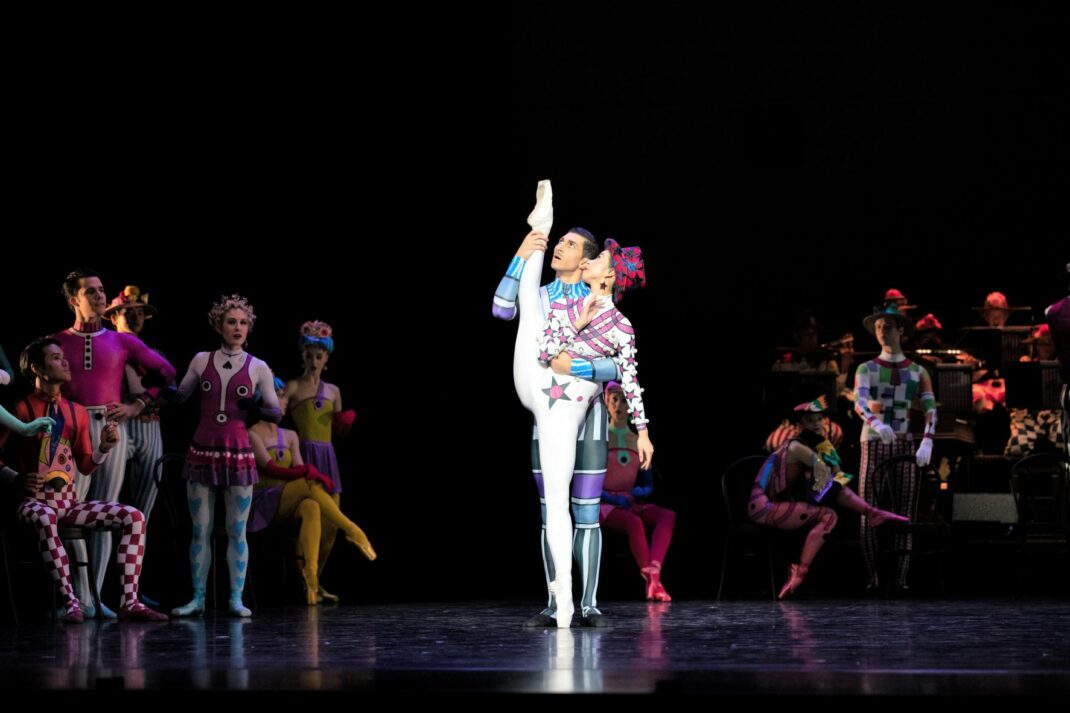

- Impermanence. Sydney Dance Company

Sydney Dance Company has begun an extensive regional tour across New South Wales, Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia of Rafael Bonachela’s 2021 production Impermanence. The tour concludes in Melbourne where it plays at the Arts Centre from 6-10 September. Don’t miss it if it is playing near you. See Sydney Dance Company’s website for details of dates and venues and read my review from 2021 at this link.

- From the past …

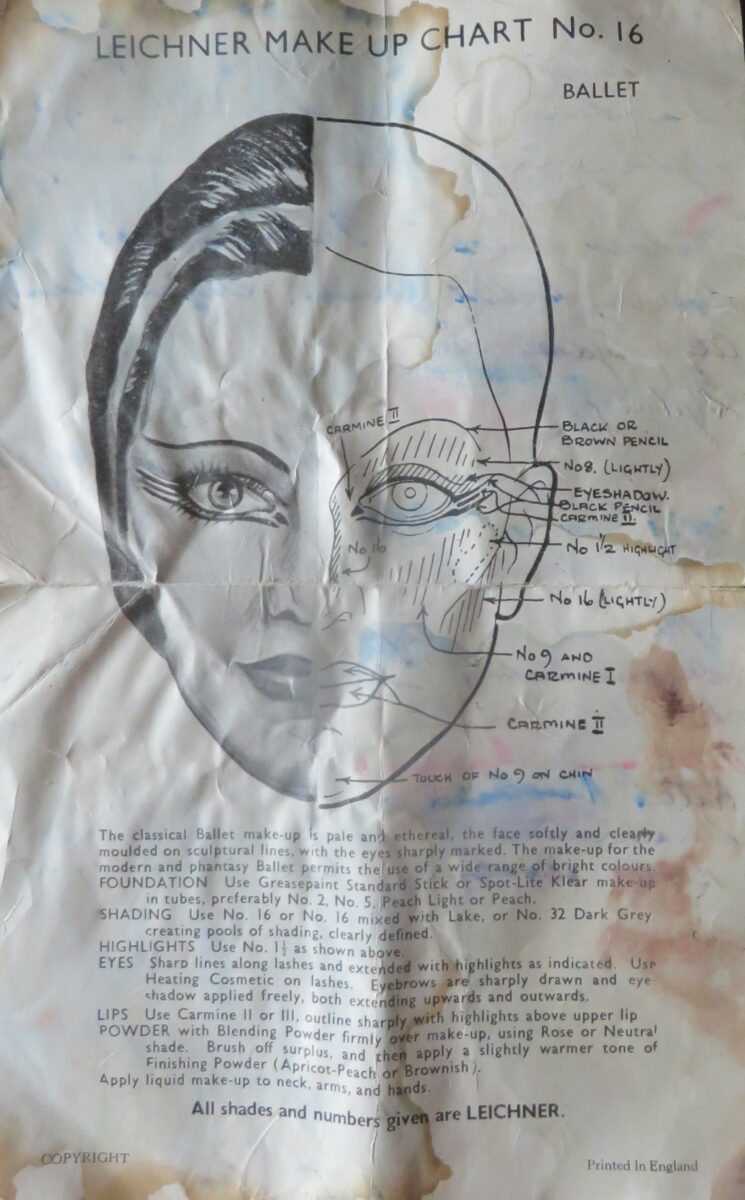

During a major clean out of a room in my house I came across a small blue case filled with Leichner products—old sticks of grease paint in numbers 5, 5½, 9 and black, and a container of ‘theatrical blending powder (neutral)’. It was my old (very old) makeup case and, as well as the greasepaint and powder, it also contained a Leichner Make Up Chart no. 16 Ballet, very crumpled and stained. On the back was a list, missing many details, of the first shows I danced in including three Christmas pantomimes, which were the first shows for which I was paid an actors’ equity salary.

Here is the list of those early performances in which I appeared, some of which I had quite forgotten about!

Aladdin Christmas pantomime, 1959

Sydney Ballet Group, Conservatorium 1960

Mother Goose, Christmas Pantomime, 1960

Sydney Ballet Group, Elizabethan Theatre, 1962

Jack and the Beanstalk, Christmas Pantomime, 1962

Musicale, Legion House, 1963

Ballet Australia, Elizabethan Theatre, 1964

Ballet Australia, Cell Block Theatre, 1965 season 1

Ballet Australia, Cell Block Theatre, 1965 season 2

Recital, Australian Academy of Ballet, 1965

Ballet Australia, Cell Block Theatre, 1965 season 3

And below is that crumpled and stained chart. Does anyone use greasepaint these days?

Michelle Potter, 30 June 2022

Featured image: Lauren Honcope speaking at a recent Ausdance ACT event.