8 March 2018, QL2 Theatre, Gorman Arts Centre, Canberra

What follows is a slightly expanded version of my review for The Canberra Times of Liz Lea’s RED. A link to the online version of The Canberra Times‘ review is at the end of this post.

The pre-show media for Liz Lea’s new work RED prepared us to expect something a little extraordinary, something a bit bawdy, something with adult themes, something fierce and fractious, perhaps something that was even a bit funny, but definitely something confronting. And yes, it was all of those things. But nothing, nothing at all, prepared us for the emotional power that coursed through RED, and for the brilliantly coherent manner in which the show drew its diverse sections together. And nothing prepared us for the courage and dignity with which Lea put her life before us, her life as a dancer who has battled endometriosis throughout her career.

RED was a multi-media experience. It began with a film clip of a young girl crossing a white bridge; the sound of a counter tenor singing that exquisitely melancholic aria ‘What is life to me without thee’ from Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice; and a voice over that began with the words ‘She thought she could have it all.’ That voice returned throughout the work. It was a doctor explaining the nature of the illness from which Lea suffered, and the procedures that she had to endure. I am told that the voice of the doctor was that of Brian Lucas, the dramaturg and Lea’s mentor for the production. Film clips from cinematographer Nino Tamburri also returned from time to time, and Lea talked about her career. Her conversation focused largely on how she managed her condition, but also went right back to her experiences as a thirteen year old dancer. Of course she also danced throughout the hour-long show.

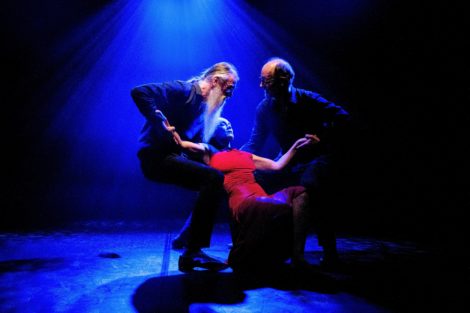

The dancing segments were fast and forceful at times, full of theatrical extravaganza at others. It was easy to see in the choreography, from three choreographers (Vicki van Hout, Virginia Ferris and Martin del Amo) in addition to Lea, the styles with which Lea is most familiar—hints of Indian dance moves, suggestions of martial arts, and a fabulous, stunningly lit showgirl routine, choreographed by Ferris and lit by Karen Norris, with feathers (red of course), fans and sequins. Then there was a ‘codeine nightmare’ when Lea was joined by several older dancers dressed in black (the women mostly with added sparkles to their dresses) who danced with and for her and helped her live out the experience of having to manage excessive pain.

But it was the ending that reduced me to tears. That incredible Gluck aria returned and Lea, now dressed in a tight, short, black number with high-heeled black patent leather shoes (with red soles), hair pulled back, and looking superbly elegant and glamorous, stood before us. She scarcely moved at first, but slowly her arms began a dance that gathered momentum and seemed to promise a future full of hope. Her limbs stretched this way and that, lyrical, questioning, wondering, and in the very last moment a shower of shiny, red “snowflakes” fell from above. The choreography for this last section was by Martin del Amo. Its simplicity was striking but it was also a breathtaking finale for all that it looked back on, and all that it promised.

RED was a truly remarkable piece of dance theatre with the coherence that only exceptional dramaturgy can achieve. Every aspect of the production was astonishing, but standing out was the power of dance, and the wider multi-media context in which it can and did fit, to transmit a diverse and very human message, and to do so with such emotion and such clarity. As for Lea, how courageous, how remarkable can one artist be? Brava!

Here is the link to the online article in The Canberra Times.

RED: the prequel

RED was launched prior to its opening night performance in one of the courtyards of Gorman Arts Centre. It was a beautiful, clear, not-too-cold night and Gorman was alive. The show was launched by the ACT Minister for the Arts, Gordon Ramsay, and his launch speech was preceded by comments from artistic director of QL2, Ruth Osborne, and Gai Brodtmann, Member for Canberra in the Federal House of Representatives.

We were also treated to a performance by the ‘wuthering’ ladies and gentlemen of Canberra who danced to Kate Bush’s 1970s song Wuthering Heights.

Also on display in one of the studios of Gorman was a collection of costumes from Liz Lea’s collection covering her productions over the past 20 years, including the costume for her solo work Bluebird. Since its premiere in London in 2005, Lea’s Bluebird has been performed across the world, with its first Australian showing taking place at the Choreographic Centre, Canberra, in 2006.

Michelle Potter, 9 March 2018

Featured image: Liz Lea in the ‘showgirl’ sequence from RED, 2018. Photo: © Lorna Sim