For reasons that escape me, my Canberra Times review of Quantum Leap’s Two Zero, filed first thing Friday morning (the morning after!), has not yet appeared online, as is the usual practice. The review may appear in the print edition of The Canberra Times on Monday 13 August. In the meantime, here is an expanded version of that review.

9 August 2018, The Playhouse, Canberra Theatre Centre

Two Zero celebrates twenty years of dance by Quantum Leap, Canberra’s youth dance ensemble and the performing arm of QL2 Dance. The program was set up as a continuous performance in eight sections, three of which were restagings of works from previous seasons with the other five being works newly created for this particular occasion.

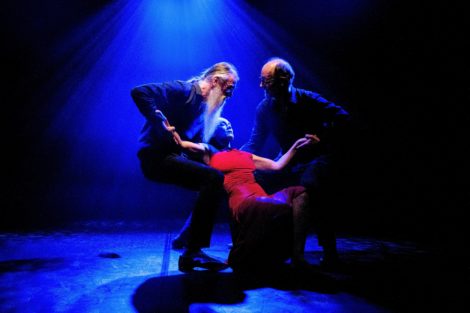

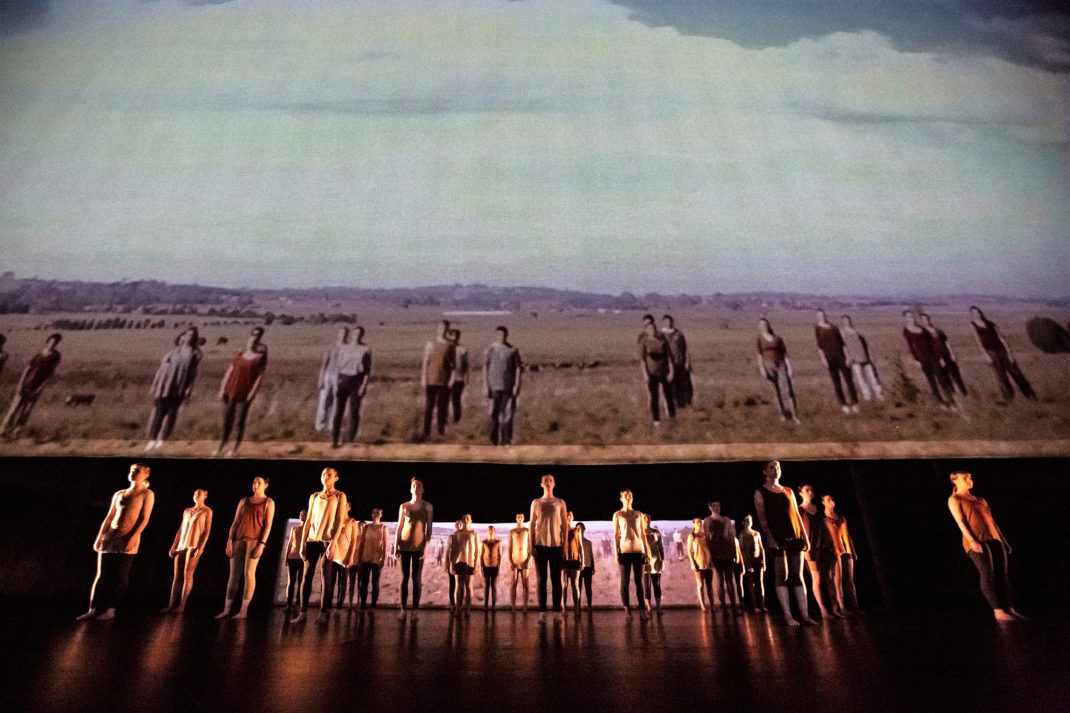

In the terms of choreography, the standout work was Daniel Riley’s Where we gather. It was first seen in 2013 as part of Hit the Floor Together and was remounted for this 2018 season by Dean Cross with final rehearsals overseen by Riley. Where we gather explored the idea of young people from Indigenous and non-Indigenous backgrounds working together. It showed Riley’s exceptional use of organic and rhythmic movement patterns, and his remarkable feel for shape, line, and the space of the stage. It had been so well rehearsed and was so beautifully danced that it was hard to accept that the dancers were part of a youth ensemble. The film that preceded it (also from 2013) was a fascinating piece of footage showing, with close-ups and long shots, dancers performing outdoors in a landscape that epitomises the ‘wide brown land’ of Australia. The seamless transition from film to live performance was engaging to say the least as a scrim that had been the screen slowly lifted to reveal the dancers onstage in more or less the same position as the final screen image. And the dancing began. Where we gather with its accompanying film opened the show and set the scene for an evening of which QL2 Dance can only be extraordinarily proud.

Jodie Farrugia’s This land is calling from the project Identify of 2011 was remounted for this season by Alison Plevey and was perhaps the most moving work on the program. Its focus on aspects of migration to Australia from the arrival of convicts to the present waves of refugee migration was powerfully yet simply presented. Suitcases were used as props by some, others had nothing, a convict was chained round the wrists. Groupings were sometimes confronting, sometimes comforting. It was a thoughtful and forceful piece of choreography enhanced by lighting and projections that opened our eyes to the extent and diversity of migration to this country.

I was intrigued by Eliza Sanders’ section called Bigger. It was a new work for ten female dancers, which examined the impact of shared female experiences and their outcomes. Sanders choreographs in a way that seems quite different from her colleagues. Her movement style is mostly without the extreme physicality of other Quantum Leap alumni and yet is fascinating in its fluidity and emphasis on varied groupings of dancers. I was not all that impressed, however, with its opening where all ten dancers were huddled (or muddled) together each holding some kind of reflecting object. It turned out to be a sort of perspex magnifying glass that indicated (we slowly discovered) the growth of experience. I could have done with less emphasis on the magnifications. The moments without them were full of joyous movement.

Other works were by Sara Black, Fiona Malone, Steve Gow and Ruth Osborne. All added an individualistic perspective to the evening.

One aspect of the show bothered me. Black and white striped, calf-length pants were a feature of the costume design for several sections and were worn under differently coloured T-shirts. They worked in some but not all sections. In Ruth Osborne’s Me/Us, a new work in which the dancers spoke of their thoughts about themselves and where they saw their place in society, they were at their best. Similarly they worked well in Steve Gow’s strongly choreographed Empower. But I thought they looked ugly underneath the white floating garments used in Bigger.

Nevertheless, Two Zero was a thrill to watch and its finale Celebrate! showed us a mini retrospective of what had happened before. The achievements of Quantum Leap, its collaborators across art forms, and the remarkable list of alumni who have emerged from it over twenty years, are spectacular. May the work continue for at least another twenty years.

Two Zero: Choreography: Sara Black, Dean Cross, Jodie Farrugia, Steve Gow, Fiona Malone, Ruth Osborne, Alison Plevey, Daniel Riley, Eliza Sanders. Music: Adam Ventoura, Warwick Lynch. Film: Wildbear Entertainment. Lighting: Mark Dyson. Costumes: Cate Clelland.

Michelle Potter, 11 August 2018

UPDATE (13/08/2018): see the shorter review online in The Canberra Times at this link.

Featured image: Scene from Where we gather from Two Zero. Quantum Leap, 2018. Photo: © Lorna Sim