Canberra hasn’t had a professional dance company for some time now and, as Dance Week 2012 approached, an article appeared in The Canberra Times in which Neil Roach, director of Ausdance ACT, suggested that the city should aspire to have an ‘emerging professional dance company … like those already being successfully funded by the Australia Council—Kate Champion, Lucy Guerin, Chunky Moves [sic]’. Well to put it bluntly, there is no reason why we in Canberra should expect to have a funded dance company. It is not a right.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t aspire to one of course. Nor that we don’t want one. But Canberra isn’t Sydney or Melbourne. It’s an unusual place and those who have watched several professional companies come and go in Canberra since 1980, when Don Asker’s Human Veins Dance Theatre became Canberra’s first professional dance company, will all have an opinion as to what suits Canberra.

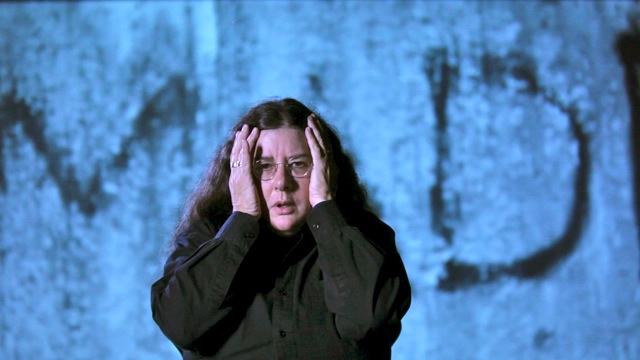

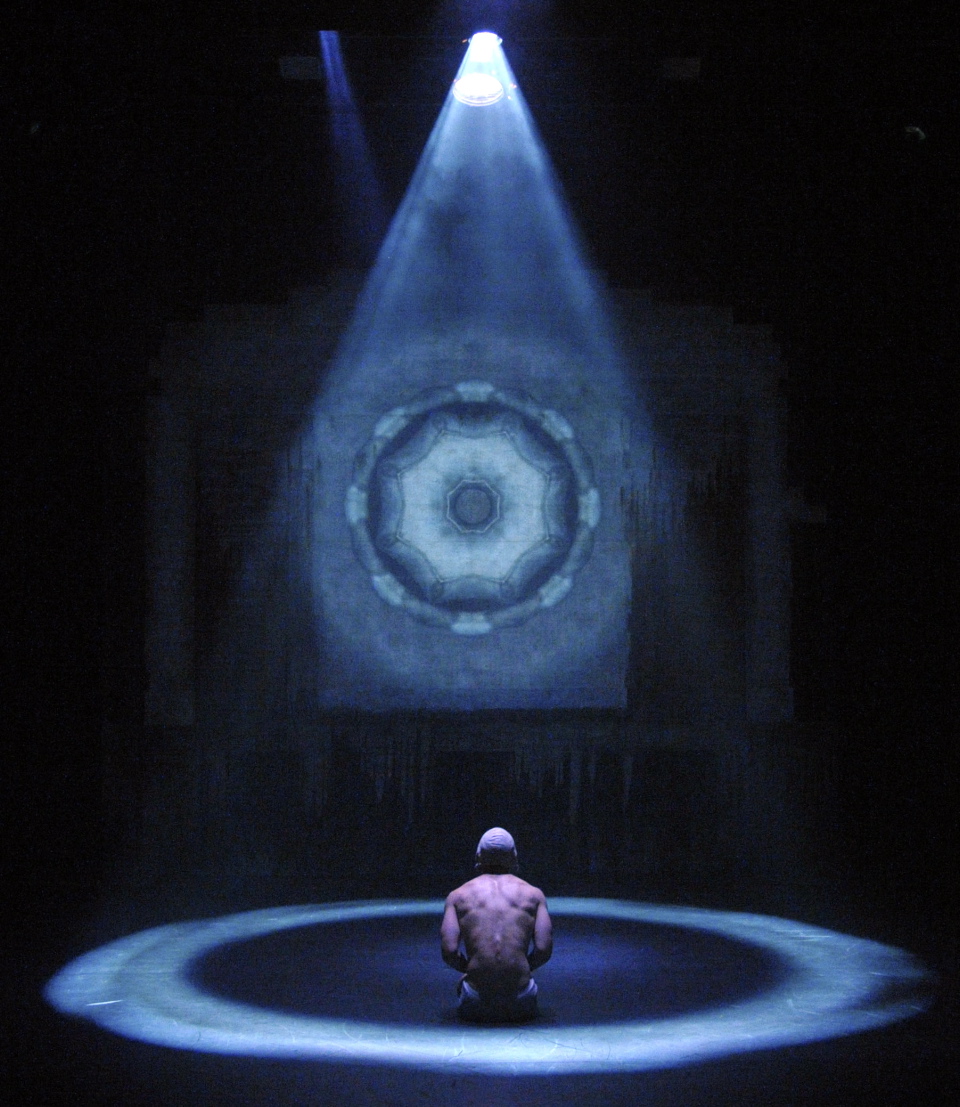

Anyone who knows me well will not be surprised when I say that for me the most vibrant time for dance in Canberra was 1989 to 1992 when the Meryl Tankard Company was the city’s resident dance company. The place was buzzing then—art attracts art—and if we look back to that period there is much upon which we can draw to make a case for what will inspire the Canberra population to embrace a dance company.

I have always been taken by the words of Stefanos Lazaridis, who directed Orphée et Eurydice for Opera Australia in 1993, which Tankard choreographed after she had left Canberra. He said on an Imagine program on SBS Television in ca. 1994:

The word ‘choreography’ did not apply as far as I am concerned. I wanted this dimension [of the opera] to be dealt with by somebody who has the demonic dance talent of Meryl Tankard, who is a woman of total theatre.

Tankard brought to Canberra something more than ‘just dance’. She brought that ‘total theatre’ that Lazaridis was smart enough to recognise and to declare in such a public forum. In my opinion that’s just what a small city needs. The population of Canberra at the moment is just 360,000. With that number of people, if a dance company aspires to be ongoing and viable it needs to be able to attract an audience from across the visual, literary and performing arts. A company that doesn’t aspire to attract, or isn’t capable of engaging audiences beyond the confines of the local dance community, will never make an impact.

Tankard was always proud that her 1989 work Banshee, shown at the National Gallery of Australia in conjunction with an exhibition of Irish gold and silver, largely Celtic jewellery, attracted a small punk audience. And I can never forget Court of Flora first staged in 1990 at Floriade, Canberra’s annual outdoor spring event. It drew large crowds, who delighted in Anthony Phillips’ spectacular costumes and in the ability of Tankard’s dancers to imbue the floral characters they represented with human characteristics. The work was repeated many times in a variety of Canberra venues between 1990 and 1992. Marion Halligan wrote about Tankard’s work. The Embassy of France and the Goethe Institute in Canberra supported the company.

But what was also interesting about those years was that Tankard and her partner in art and life, Régis Lansac, embraced the Canberra community, its institutions, its landscape and its resident artists. They lived in the city. Lansac exhibited his photographs with other local artists. Tankard made a short film in the Federal Highway Park Quarry just out of the city. Lansac incorporated photographs of a local landmark, Mount Ainslie, in projections that accompanied Two Feet. Lansac received a Canberra Critics’ Circle Award for ‘his constant searching for, and discovery of, new frontiers in stage design’. And ultimately Tankard was made ACT Citizen of the Year in 1992 for having ‘brought the arts in Canberra to both national and international attention’ and for ‘enriching [Canberra’s] reputation as one of great diversity and creativity’. It was a heady time for dance in the ACT and one that has not been equalled since in my opinion.

So yes, I too would love there to be a professional dance company in Canberra. But I don’t think it should be an experimental, contemporary company with interests that attract only a minority of dance aficionados. Leave that to larger cities. Canberra needs a dance company that the wider community can feel belongs to Canberra, not just to dance.

Michelle Potter, 28 April 2012.