7 May 2022 (matinee). Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

David Hallberg has given his directorship of the Australian Ballet a name, a conceptual idea, for us to ponder—’A New Era’. The company’s latest production, Kunstkamer, brings reality to Hallberg’s concept. Kunstkamer is a complete change for the Australian Ballet. It is a magnificent, brilliantly conceived, exceptionally performed work giving audiences (and perhaps even the dancers) a whole new look at what dance can achieve, and maybe even what we can expect for the next several years under Hallberg?.

Inspired by an eighteenth-century publication Cabinet of Natural Curiosities, and first performed by Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT) in its 2019-2020 season, Kunstkamer (literally art room in Dutch) is the work of four choreographers, Sol León, Paul Lightfoot, Crystal Pite and Marco Goecke. Cabinets of curiosities date back several centuries and were collections of paintings and other items—curiosities—from around the world and were precursors to what we think of today as museums. Kunstkamer is a dance work in 18 separate sections and, to my mind, fits beautifully within the notion of a collection of unusual, beautiful, incredible items, and even within the idea of a room or several rooms containing such items.

Take the set by León and Lightfoot and the lighting (Tom Bevoort, Ubo Haberland and Tom Visser) for example. The set was architecturally inspired and as each dance section began the screens that made up the set slid into a new formation, or lighting changed our perspective of the ‘room’. It was as if we had moved from one room of a museum to another. Of course there are other ways of looking at how the set was used. Dancers entered and left through a series of doors built into one part of the set, often slamming them noisily. Coming and going. Changing styles. Any number of thoughts come to mind.

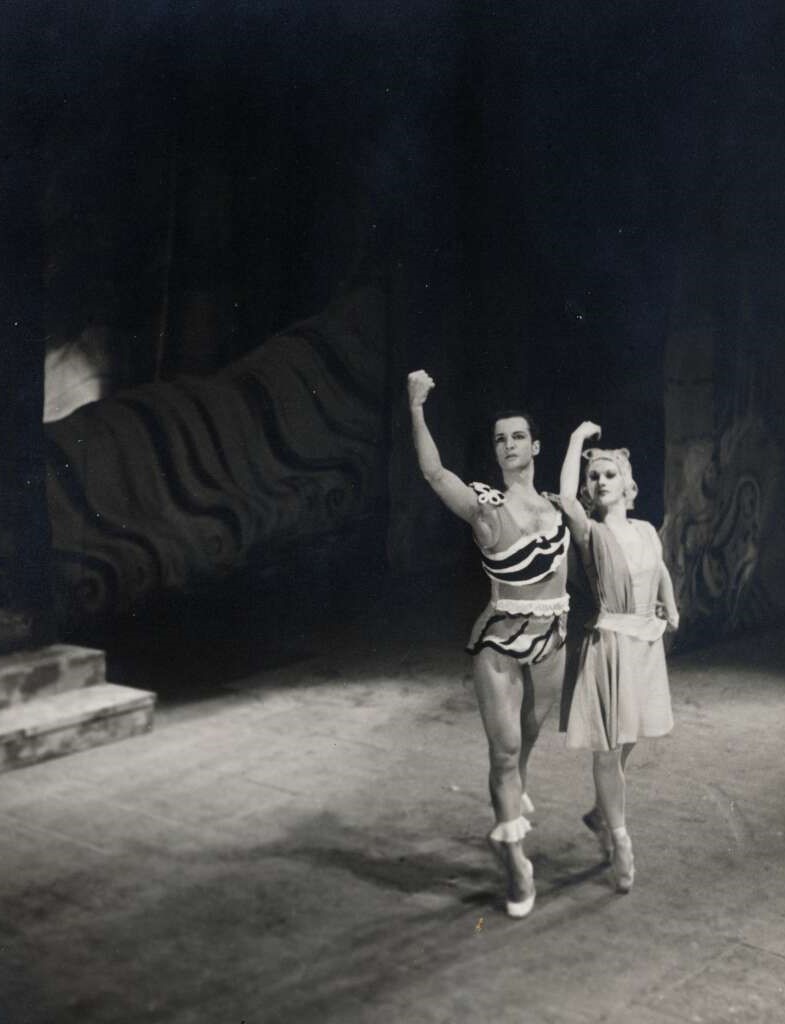

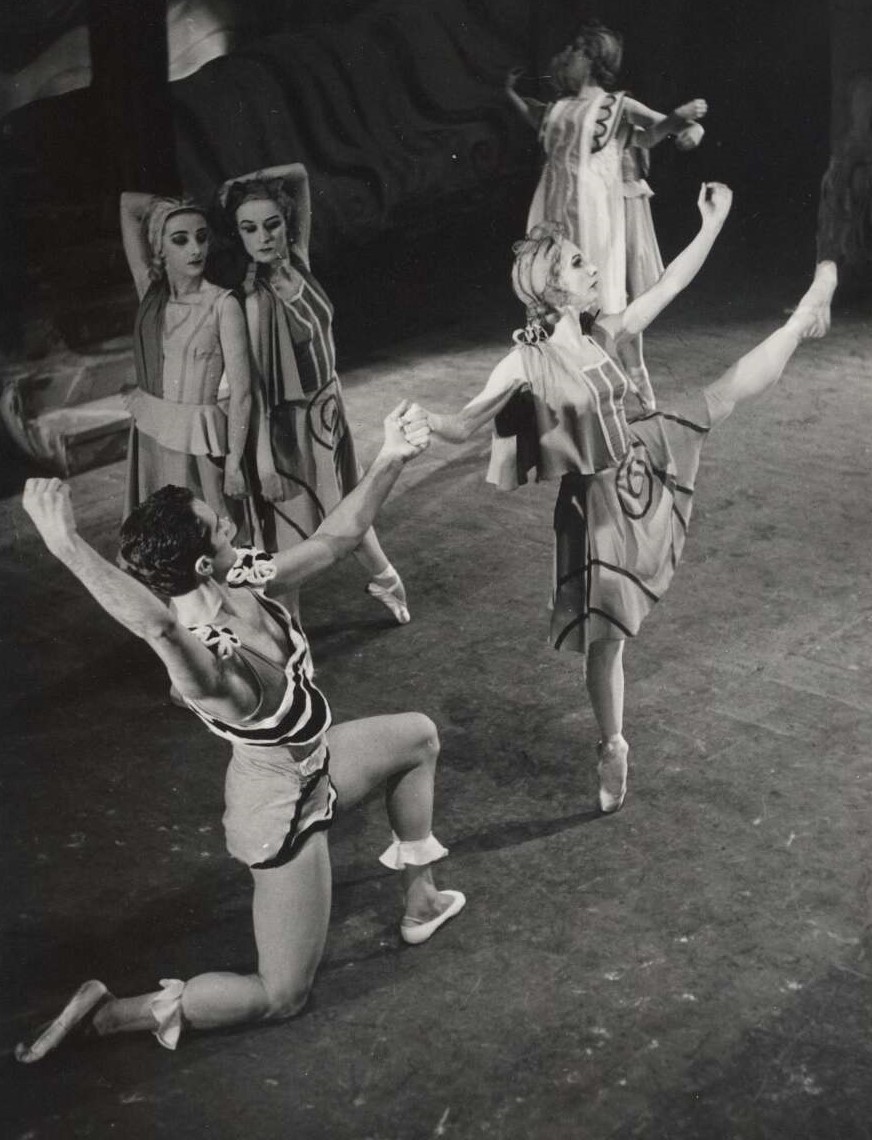

Then there were the various sections that made up the dance component. Each section was unique and all carried allusions of various kinds—to the work of other choreographers for example and William Forsythe and Jiří Kylián spring straight to mind. The opening scene for Part II, seen in the image below, was motionless but somehow incredibly moving and, as the dancer sat there, a front curtain descended and rose again reminding us of Forsythe’s Artifact. Then there were references to various trends in the visual arts, especially those of the late 19th, early 20th century; and even allusions to other theatrical styles, Butoh for example when dancers appeared white-faced and open-mouthed.

As for the choreography, it was contemporary movement—angular poses, stretched limbs, movement that often seemed quite raw rather than controlled, but often an emphasis on group shapes and unison movement.

The standout dancer at the performance I saw was Benedicte Bemet, who seemed totally transformed. I have always admired her dancing but this time gone was the ‘ballerina look’ (as beautiful as that can be) and there onstage was an artist able to move into a new world when required. She was magnificent. I also particularly enjoyed the performances by Callum Linnane and Adam Bull and the very strong introductory moments from guest dancer Jorge Nozal, who appeared with NDT in the same role (described in the printed program as ‘the enigmatic ghost character’). But every dancer rose to the occasion brilliantly. I got the feeling that they just loved dancing Kunstkamer with all its weird and wonderful aspects, including the speech, often incomprehensible chatter, and the singing by the dancers that was included. The music itself was as as varied as the choreography and ranged from Beethoven to Janis Joplin and included at one stage a pianist playing onstage.

What an unbelievably incredible show this was from beginning to end! I understand it is being streamed on 10 June. If you can’t get to see it live, check out the streaming details.

Michelle Potter, 10 May 2022

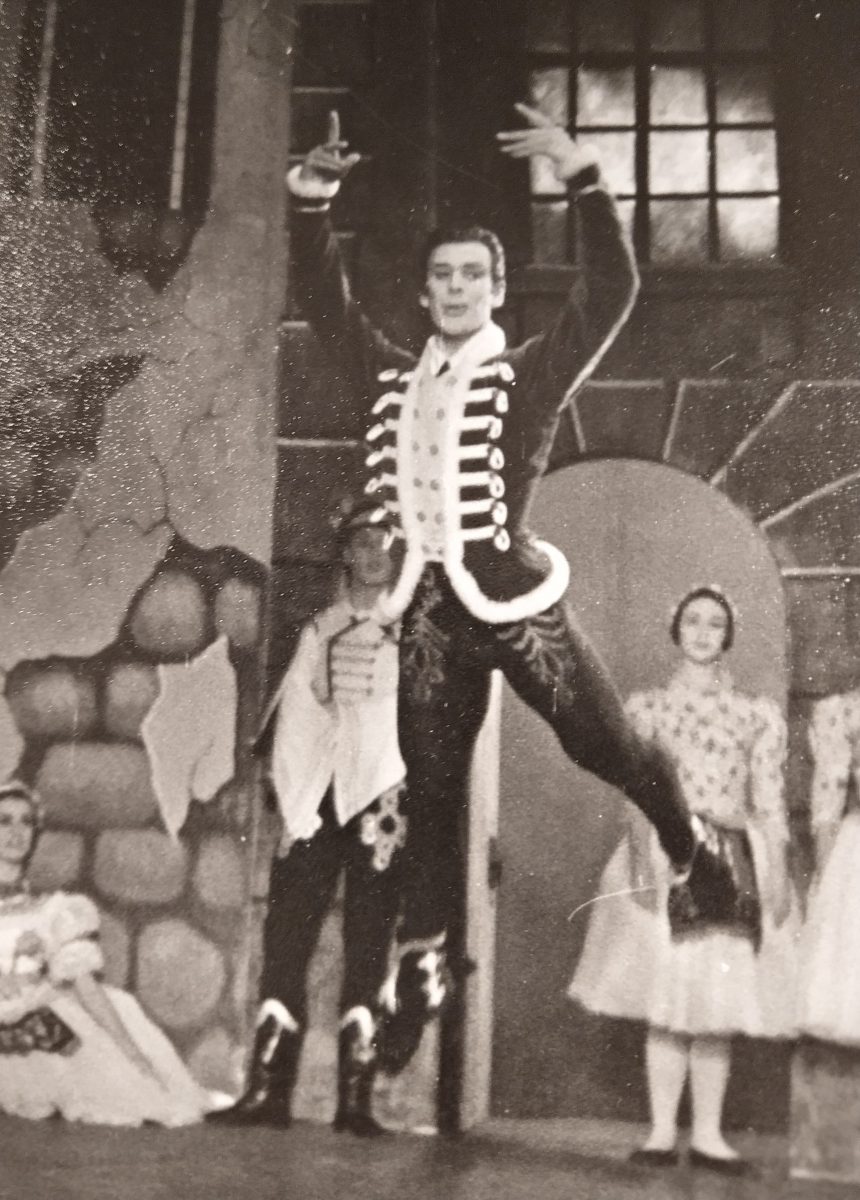

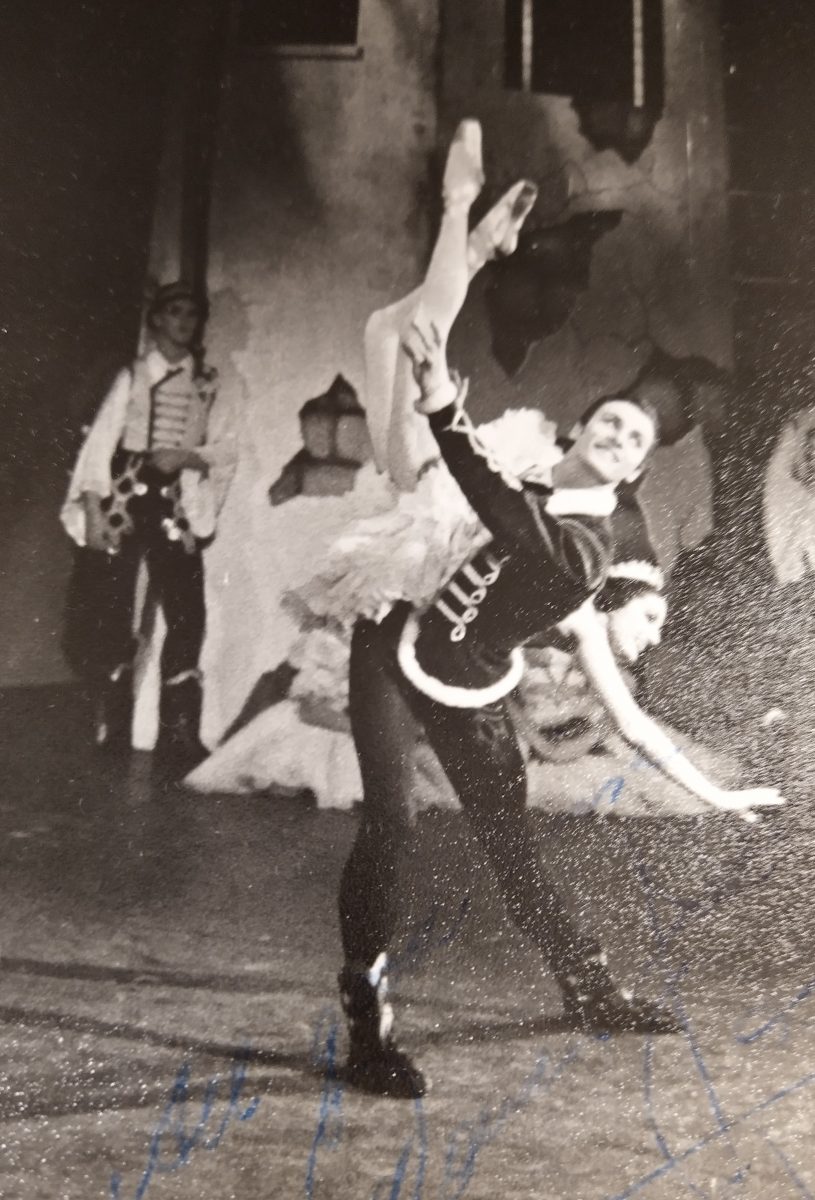

Featured image: Benedicte Bemet in Kunstkamer. The Australian Ballet, 2022. Photo: © Daniel Boud