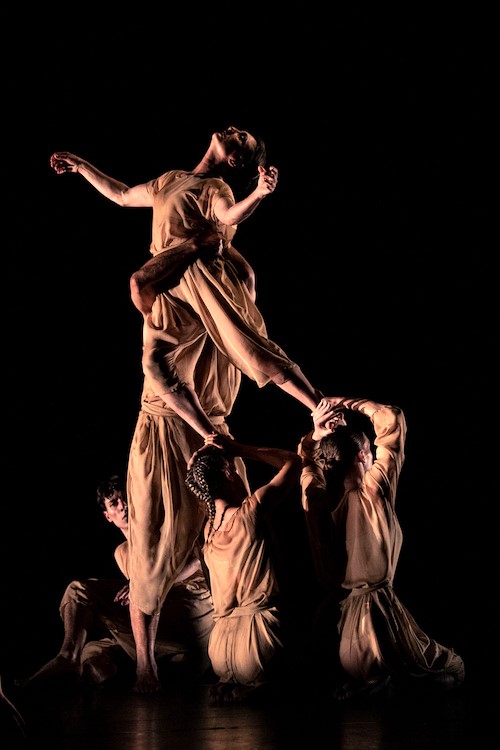

20 January 2023. Carriageworks, Eveleigh. Sydney Festival

In 2012 I self-published a biography of Meryl Tankard, which for better or worse I entitled Meryl Tankard. An original voice. Well rarely has that ‘original voice’ been so noticeable as it was in Tankard’s latest work, Kairos. The word ‘kairos’ means (in Greek) ‘the right or opportune moment for doing, a moment that cannot be scheduled’ and media information tells us that Tankard’s Kairos was a response to the uncertain and challenging times in which we live, and especially the circumstances in which the work was made. ‘The right and opportune moment is now’, we were told.

The work was really a collection of solos for each of the six dancers Tankard worked with to create Kairos: Lillian Fearn, Cloé Fournier, Taiga Kita-Leong, Jasmin Luna, Julie Anne Minaai and Thuba Ndibali. A young girl, Izabelle Kharaman, joined the group on two brief occasions. As is her usual practice, Tankard acknowledged the dancers as collaborators, although it is hard to know just how much of each solo was from the dancers and how much from Tankard. Each dancer had a very distinctive way of moving so there was no strong choreographic through-line, although there were moments when Tankard-esque features surfaced. The frequent tossing of her long hair by Lillian Fearn, especially towards the end of the work, was one such feature. But only rarely did the dancers work as a group.

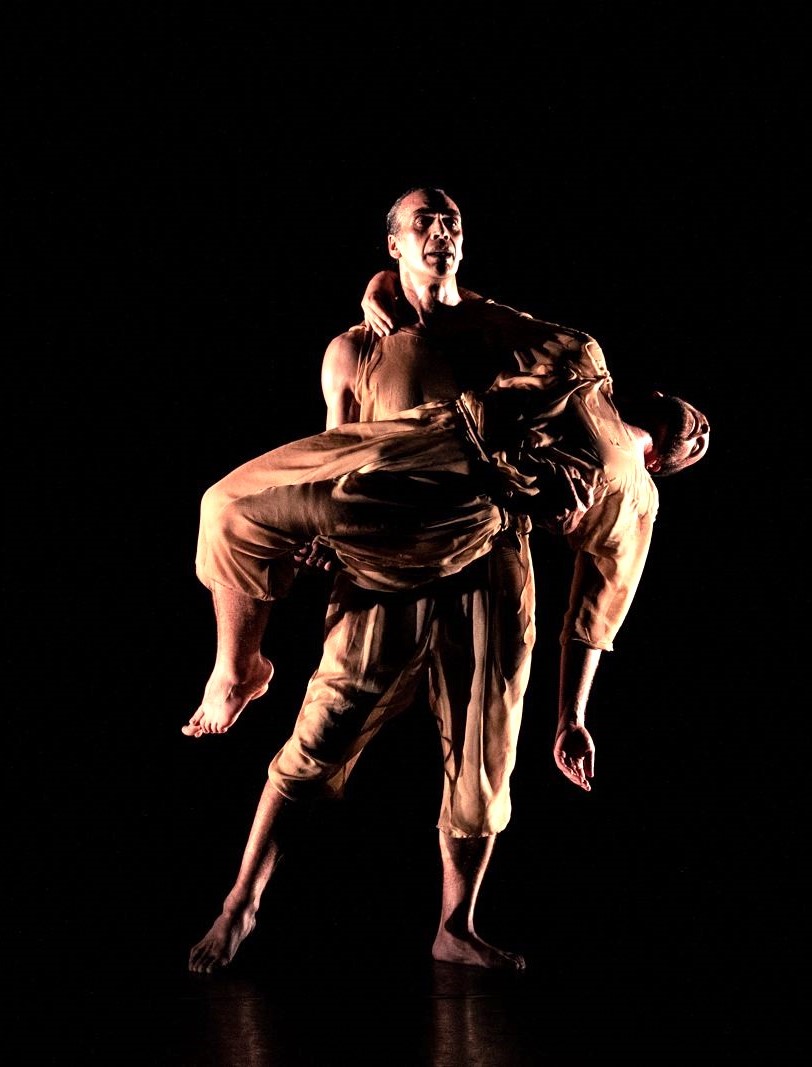

I especially enjoyed Thuba Ndibali’s movement, especially the way he used his long, loose limbs, although not so entertaining was his duet (of sorts) with Taiga Kita-Leong when Ndibali treated Kita-Leong as a kind of dog (slave?). I also admired Fearn whose elegance and strength of presence was mesmerising. But each performer seemed involved in his or her own activities and thoughts so there seemed to be no narrative through-line. In the end I gave up trying to decide what each moment meant. They could have meant anything according to how one was feeling or thinking at the time.

One or two moments were annoying, to me anyway. But then perhaps that was part of the whole. Not everything makes us happy, not in troubling times, not ever really. I wondered why, for example, at one stage the dancers appeared with boxes over their heads with the boxes having pictures/photos(?) on the front of the box. They were meant to refer to a period in the life of Australian artist Sidney Nolan when he was creating portraits using a particular medium that Tankard and her creative team found unusually interesting. But for me the parading with the boxes was pretty much meaningless and perhaps even insensitive to Nolan’s practice.

Another moment that was frustrating was when Cloé Fournier stood on a stool and recited in French a poem by Arthur Rimbaud, Le dormeur du val (The Sleeper in the Valley). The French is not difficult to understand but I could not hear every word being spoken. There was a lot of ambient sound and Fournier’s projection was not always strong enough to overcome other noises. This was a shame because the poem is fascinating for the way it presents the image of a soldier apparently asleep but actually dead, having been shot. Here was one moment when at least one idea stood out—appearances can be deceptive—but we missed it by not hearing the full version of the poem.

Looking more positively, however, visually and musically Kairos was completely absorbing. Régis Lansac’s video design and photography were brilliant. I was especially taken with some early moments in the work when the backcloth of scrims had changing images of a bush landscape projected on it. Mysterious figures hovered in the background, and bird sounds and other bush noises filled the air. Such atmosphere! The lighting by Verity Hampson was also outstanding. The accompanying and inspiring score was by Elena Kats-Chernin, who performed live on a grand piano that was situated mostly in a downstage corner, but that was pushed by the performers into a centre stage position towards the end of the work.

Tankard’s original voice was certainly there on show in Kairos. It was especially obvious in her powerful aesthetic of collaboration, but not always in the positive manner that I remember from her works made in Canberra and Adelaide. There was much that was puzzling about Kairos, largely because of a lack of easily understood themes and from choreography that seemed messy in its diversity, even though it was mostly performed skilfully. As a result, I thought that for the audience a certain negativity permeated the work. Kairos reminded me of an article by Helen Shaw, which appeared recently in The New Yorker entitled New York’s Theatre Festivals Imagine a World After Mankind. In it Shaw examines ‘visions of the future’ and finds that in several shows she has seen recently she has been somewhat dismayed to notice in the performances a delight in, and savouring of the disappearance of the world as we have known it. Dance doesn’t have to be like that, although it seems more and more as if that is the way it is going.

Michelle Potter, 22 January 2023

Featured image: Lillian Fearn in Meryl Tankard’s Kairos. Photo: Régis Lansac