- Mirramu Dance Company

The dancers of Elizabeth Dalman’s Mirramu Dance Company are currently in residence at Mirramu Creative Arts Centre, on the shores of Lake George, Bungendore, rehearsing for L. The current Mirramu company consists of Dalman herself, Vivienne Rogis, who co-founded the company with Dalman, Miranda Wheen, Janine Proost, Amanda Tutalo, Mark Lavery and the newest recruit, Hans David Ahwang, a recent graduate from NAISDA.

L is the story of a vibrant life, that of Elizabeth Dalman. It began as Sapling to Silver in 2011 and in that form won a Canberra Critics’ Circle Award. Dalman is reworking it and tightening the production, and she has renamed it L for its upcoming performances in Queanbeyan and at a gala event in Adelaide in celebration of the 50th anniversary of Australian Dance Theatre. L is the roman numeral for 50 and also the first letter of Liz, the name by which Dalman was known as founding director of ADT. While L is autobiographical, Dalman sees it as an Everyman story, the story of every dancer and every artist facing the pleasures and the difficulties of a creative life. It is also the story of every human being facing the ageing process and pondering how to communicate knowledge to a younger generation. As such it seems a perfect way to celebrate 50 years of ADT as well as the contribution Dalman has made across those 50 years.

L is at the Q, Queanbeyan Performing Arts Centre, on 15 July; and at the Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide, on 18 July.

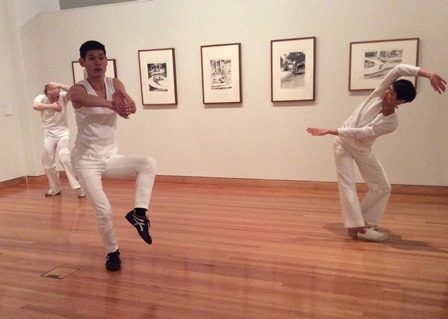

- Hans David Ahwang

Meet the newest member of Mirramu Dance Company.

Ahwang is a Torres Strait Islander from St Paul’s Community of Moa Island. He graduated from NAISDA in 2014 with a Diploma of Careers in Dance Performance. As well as performing with a range of companies during his time at NAISDA, Ahwang was a model at the first Indigenous Fashion Week in April 2014. I look forward to his performances in L, and to following his dance career.

- Strange attractor: the space in the middle

Now in its third year, Strange attractor, a Canberra-based initiative, brings together several independent choreographers, and a range of other contributors, in a choreographic lab where the choreographers have freedom to explore a particular project. This years lab was facilitated by Margie Medlin and choreographers were Alison Plevey, Amelia McQueen, Janine Proost, Laura Boynes and Olivia Fyfe. I can’t say I really understood what was behind every project and I have always disliked program notes that refer to concepts that are beyond the ken of many in the audience. Nevertheless, there was some interesting dancing and some quite stunning dance photography by Lorna Sim.

Although I can’t say Amelia McQueen’s first project, which was an audio piece, thrilled me much, I enjoyed her dancing in her second project, in which she re-enacted a duet between dancer and guitarist. I was also fascinated by Alison Plevey’s work with its ‘strange attractions’ of dancers hidden in black costumes but sporting some kind of lighting tube on their costumes.

Strange attractor is an important project. Choreographers need the space to experiment without fear of criticism before their projects are fully formed. But to the organisers, please remember the (future) audience. Dance will only survive if an audience will come and see what has been created. It doesn’t have to be simplistic, but it can’t be abstruse.

- Kathrine Sorley Walker

I learnt just recently of the death in April of Kathrine Sorley Walker at the grand age of 95. Australian dance historians (and others) must be eternally grateful to her for bringing the Ballets Russes Australian tours to the fore in her book De Basil’s Ballets Russes, first published in 1982. Her chapter on Australia certainly informed my work on those momentous tours, including my initial foray into that time for my undergraduate honours thesis in the Department of Art History at the ANU.

Her other contribution to Australian dance history is her work on Robert Helpmann, which appeared in book form and in a series of articles in Dance Chronicle. I have always felt she saw Helpmann through rose-tinted glasses but, as with her Ballets Russes work, it provides a great starting point for further research.

An obituary published by London’s Telegraph is at this link.

Michelle Potter, 30 June 2015