- Luke Ingham

In mid-March I had the pleasure of meeting up in San Francisco with Luke Ingham, former soloist with the Australian Ballet. Ingham and his wife, Danielle Rowe, left Houston Ballet in 2012 to take up other offers. Rowe went to join Netherlands Dance Theatre in The Hague and Ingham scored a soloist’s contract with San Francisco Ballet. Ingham has already had some great opportunities in San Francisco and my story on his activities is scheduled to appear in the June issue of Dance Australia in the magazine’s series Dancers without borders. Watch out for it.

- Walter Gore’s The Crucifix

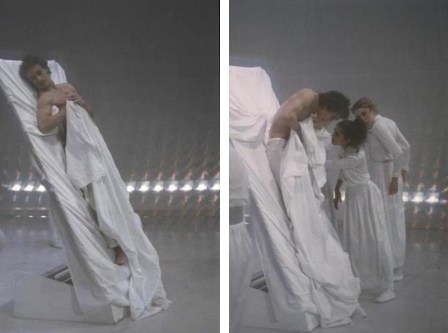

I have always been fascinated by a photograph taken by Walter Stringer of the final scene from Walter Gore’s ballet The Crucifix. Alan Brissenden, in his and Keith Glennon’s book Australia Dances, reproduces the photograph on page 53, and a print is part of the National Library’s Walter Stringer Collection. Brissenden gives a brief account of the storyline and the reception the ballet received when it was staged in Australia by the National Theatre Ballet in 1952.

I have just recently been making a summary of an oral history interview I recorded with Athol Willoughby in February and his recollections of performing in The Crucifix tell us a little more, especially about the final scene, and provide, furthermore, a wonderful example of the value of oral history. Willoughby played the role of one of the soldiers who accompanies the executioner, played by Walter Gore, to the scaffold. He says of the opening performance:

‘The scene changed to a huge [stake] with a lot of fake wood around it … Wally came in carrying Paula … Her hands were tied … and he lifted her onto the [stake]. Just as the symphony ended he picked up a torch—none of us had seen the end of the ballet, even at the dress rehearsal the end of the ballet hadn’t been choreographed and we didn’t know what was going to happen—he picked up a flaming torch and threw it at the pyre of wood. The minute he threw the torch at her the wood lit up, the symphony finished and Paula screamed … It was so powerful.’

- The Rite of Spring: an animated graphical score

I have just received the following note and link from composer Stephen Malinowski:

‘The last few months, I’ve been working on an animated graphical score of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. This week I completed the first part. Enjoy!

- Pacific Northwest Ballet

In my review of Pacific Northwest Ballet’s recent program I mentioned that the show I saw was only the second time I had seen the company in performance. Well that is not quite true. I had the good fortune to see the company in 2007 in Seattle when the program consisted of George Balanchine’s La Sonambula, Christopher Wheeldon’s Polyphonia and Nacho Duato’s Rassemblement. Certainly a very interesting program.

Michelle Potter, 31 March 2013

Featured image: Luke Ingham and Sarah van Patten in Christopher Wheeldon’s Within the Golden Hour. Photo: © Erik Tomasson, 2013. Courtesy San Francisco Ballet