West Australian Ballet’s Cinderella, newly created this year, had a season in Canberra in November and its popularity was such that an extra show needed to be scheduled. I had certain expectations, having spoken previously to the artistic director of WAB, the choreographer and the designer before writing a preview piece for The Canberra Times. All spoke eloquently about the process of creation and their aspirations for the piece.

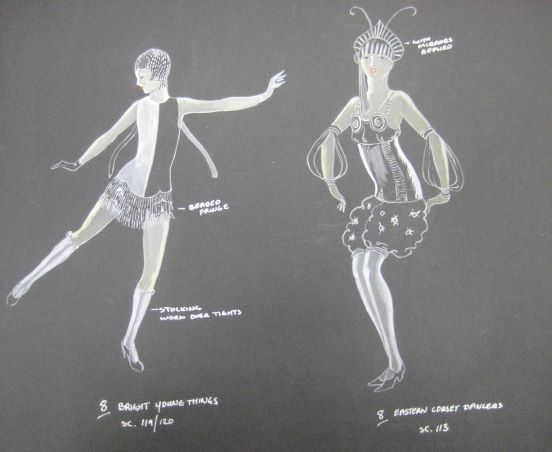

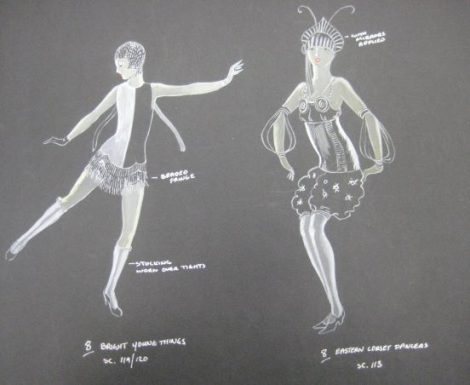

But when it came to the performance itself I have to say I was heartily disappointed. While I enjoyed the design by Allan Lees, which set the work in the 1930s, I thought the choreography, by Jayne Smeulders, was scant and quite simplistic. There were many moments when the stage (and I’m talking here about the much-maligned stage of the Canberra Theatre, which is reputed to be too small for the larger kind of ballet production) seemed positively empty of dancing. Not only that, or perhaps because of that, the dancers rarely looked as though they were full-scale professional dancers.

Wherever I have worked in my journalistic dance writing life to date there has always been a policy in place that the person who writes the preview does not write the review of the same piece. My experience with WAB’s Cinderella hammered home the sense behind that policy. But seeing this Cinderella made me wonder about another newly created Cinderella, that by Meryl Tankard for Leipzig Ballet. It opened in Leipzig on 5 November.

Unfortunately I have neither spoken to Tankard about the work nor seen it but the web at least allowed me to catch a glimpse of some images, a bit of footage and snatches of an interview with Tankard about the work. I was interested in Tankard’s answer to a question posed to her by Maeshelle West-Davies from the Leipzig Zeitgeist about why she chose Cinderella and what she thought she could bring to the work. Part of her reply said:

‘Since I am quite used to spending a lot of my time on long trips to and from Australia, I decided to use this experience in Cinderella. The story begins in an airport with Cinderella, and the very ‘glamorous!’ sisters, travelling to an exotic location for a huge party hosted by a wealthy prince. A lot of the scenes will be in ‘hotel rooms’ and the garden scene has been influenced by Sydney’s beautiful botanical gardens. I would like the audience to feel as if they have also been on big trip!’

As thought-provoking too was her reply to a question concerning her process, which seems somewhat different from her process with many of her works made in Australia:

‘I had to be very well organised for Cinderella. I didn’t get much time with the dancers, as they were rehearsing a lot for other productions. I also had to make a lot of decisions about editing the music very early on, so I had to have a clear structure before I began working with the dancers. Since Cinderella is a very well-known story, I had to come up with a new and original way to tell the tale. I approached it as if I were planning a film and storyboarded all the scenes before I arrived in Leipzig.’

A trailer available on YouTube gives a glimpse of the choreography and the design, including the kinds of projections we have come to recognise as signature Tankard/Lansac. Some of the lighting and projections reminded me of sections of Wild Swans, which is not a bad thing in my opinion. I often ponder how Wild Swans the ballet has pretty much slipped from view whereas Elena Kats-Chernin’s delicious score, or parts of it, are heard often. Such is dance I guess.

It seems unlikely that we will see Tankard’s Cinderella in Australia, at least not in the near future. It sounds and looks (at least from a brief glimpse) as though it might be an engrossing take on the fairy-tale. But am I falling into the same trap as I did with WAB’s Cinderella? Such are expectations.

Michelle Potter, 4 December 2011