In December 2002 I wrote an article, at the request of Bruce Marriott, for ballet.co magazine (now no longer available) to coincide, if I remember correctly, with a conference of artistic directors held in the United Kingdom somewhere (perhaps London?). I think the commission came because David McAllister, then quite new in the role of artistic director of the Australian Ballet, was attending. As with many of my other articles and reviews for ballet.co, I thought it had disappeared from my computer files and I had not made a print out. But just recently it appeared when I was searching with the term ‘Nutcracker’ for another thought-to-be lost file. So I am posting it here and welcome comments from a 2018 perspective.

As artistic directors of some of the world’s best-known ballet companies meet to discuss the issue of globalisation, I am reminded of a now well-known debate that emerged in Australia in the 1960s and the 1970s. It concerned the nature of the country’s cultural development. Two camps sprang up: one centred on the idea of the tyranny of distance, the other on the notion that from the deserts the prophets come. Those who spoke for the tyranny of distance believed that Australia was a cultural desert isolated from the great centres of civilisation, especially from the so-called mother country of Great Britain. Those on the other side believed that Australians did not need to rely on their colonists for what they required to nourish their souls—in the midst of their isolation they could have their own uniquely beautiful culture that could define them, equally uniquely, as Australian. This group took as a catch cry some lines from a poem written by renowned Australian poet A. D. Hope in 1960:

Hoping, if still from the deserts the prophets come

Such savage and scarlet as no green hills dare

Springs in that waste.

The debate is historically interesting, and the discussion generated two of the best-known period books on Australian culture and identity: Geoffrey Blainey’s The Tyranny of Distance and Geoffrey Serle’s From the Deserts the Prophets Come (later, in an attempt to popularise, or globalise perhaps, the Serle book was renamed The Creative Spirit in Australia).

Advances in technology of various kinds have, of course, made the idea of the tyranny of distance pretty much an obsolete concept. Globalisation, however, is clearly with us: it is part of the fabric of our contemporary existence. It has permeated every aspect of the way we live and operate in the twenty-first century. And while many of the inhabitants of the northern hemisphere may still think of Australia as out of scope, few Australians (thankfully) now believe that distance hampers their ability to interact with the rest of the world. So where does this leave the individualism that we rightly prize so highly? What do we do with the savage and scarlet that has so flamboyantly grown? Or even with the green hills if we are on the other side of the world? Do we sit back and allow globalisation to turn what is unique about our individual dance cultures into something bland and universal? Or do we embrace culturalism, accepting that, while communications may have changed the way we operate in the world, our individual cultures cannot develop in a similar way? Do we sit in our theatres from London to Sydney, from New York to Melbourne, all seeing the same works: a Giselle respectfully produced, Manon, a couple of items from Balanchine, The Merry Widow and so on. Or do we each go for something culturally specific (a Murphy Nutcracker, an Ashton work from the early repertoire), and for individualistic reworkings of the tried and true (a Guillem Giselle, a Murphy Swan Lake)? Is one way the only way? The right way? The wrong way?

Neither bowing to globalisation nor strictly adhering to culturalism is the answer. Culturalism smacks of attitudes of superiority and cultural elitism—my culture is better than yours. It closes the mind to innovation and change. It indulges in smugness and name calling (the vile expression ‘Eurotrash’, beloved by one particular British critic, springs immediately to mind). It is a stultifying attitude. On the other hand, globalisation removes what we value about ourselves as individuals in unique cultures, what our specific histories have created and asked us to cherish. But defiantly, ballet is perfectly able to accommodate itself within a global society without losing anything. Ballet isn’t dying. It isn’t even at the crossroads as it encounters globalisation. Ballet is like a sponge. It can soak up change: it has been doing so for centuries. It can absorb new vocabulary. It can keep renewing itself from what it absorbs. It has to be able to operate in this way because it is a living, breathing art form. Even the most superficial glance at photographs of acclaimed dancers in the same role taken over several decades, in Giselle for example, makes it very clear that while we may want Giselle to stay the same—the past is very comforting—it can’t and hasn’t and won’t. In fifty years time dancers won’t want to dance Giselle like Alina Cojocaru (hard as that idea may be to comprehend at the moment).

In the twenty-first century the ballet-going public is entitled to green hills sprinkled liberally with some savage and scarlet (and I mean this more widely, more figuratively, than simply British works sprinkled with Australian ones). Dancers are, for their growth as artists, entitled to experience the work of choreographers outside their immediate, culturally-specific environment. Choreographers are entitled to wonder (and experience) how their works might look when danced by dancers trained outside the choreographer’s home country: the great ones do (and have) and are open and generous about the experience, as any dancer from the Australian Ballet who has worked with Jiří Kylián on any work from the Australian Ballet’s Kylián repertoire will tell you. Critics need to open-minded enough to embrace change and innovation while caring about the past. And artistic directors need to understand it all! The artistic director of a truly great company needs courage, intelligence and drive. Courage not to be swayed from his or her vision. Intelligence to have a vision that looks both forward and in a lateral direction and, going hand-in-hand, intelligence to understand that looking in this manner and direction is not a denial of the past. Drive to put the vision into practice.

Globalisation is a much-maligned concept. It doesn’t have to exclude anything really. But to react to globalisation uncritically, and to allow it to dictate to us is the problem. To do this is to lack courage, intelligence and drive. That we can see new works and restagings of old ones from London to Sydney, New York to Melbourne is a gift of globalisation. If we wish to deny that gift by insisting on culturalism it is a measure of an inability to exist in a global culture, in today’s culture, and a pitifully conservative attitude. But one thing is certain, whatever the response of individual people ballet will keep moving forward. It will never fall victim to a narrow culturalism. Only people will do that. Let’s hope that the new breed of artistic directors understands.

Michelle Potter, December 2002, reposted 14 June 2018

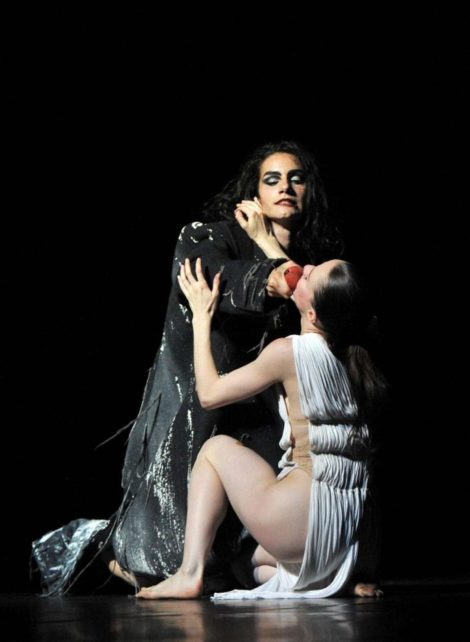

Featured image: Artists of Finnish National Ballet in Sylvie Guillem’s Giselle, 1998. Photo: © Kari Hakli