14 November 2015 (matinee), Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

What a pleasure it was to see the Australian Ballet’s triple bill program, 20:21, for a second time, in a different theatre, and with a different cast. Clearly the dancers have become more familiar with the works over the series of performances that have been staged since I saw it in Melbourne. I suspect it also looks better on the smaller stage of the Sydney Opera House (for once). In addition, I have inched myself forward over many years of subscribing to a Sydney matinee series so that I have an almost perfect seat in the Joan Sutherland Theatre. It all adds up.

This time In the Upper Room had a simply fabulous cast. Daniel Gaudiello and Natasha Kusch were stunning throughout, as were Ako Kondo, Miwako Kubota, Ingrid Gow (great to see her in a featured role again), Chengwu Guo and Christopher Rodgers-Wilson.

These seven dancers worked together in different combinations in the more balletic of the various sections of Upper Room. Not only did they show off their superb technical skills, they brought their individual personalities to these sections—a perfect approach for Tharp’s choreography. Gaudiello finished off his phrases of movement with his remarkable sense of theatricality; Guo finished his with a kind of nonchalance, which was equally as satisfying. But it was Kusch who stole the show with her joyous manner and her ability to make even the most difficult move, the most outrageous lift, look so easy.

It is such a thrill to see this work performed by the Australian Ballet’s dancers and it was not just the seven I have mentioned who danced wonderfully. I could feel the excitement building from the moment the curtain rose on Dimity Azoury and Vivenne Wong in their sneakers and stripey costumes. As I have said before, for me the Australian Ballet’s dancers have the staying power, the determination to succeed,and just the right personalities to make Tharp’s Upper Room look fabulous. This time they nailed it and for once I didn’t keep thinking of previous casts I saw umpteen years ago!

Kusch was also the star attraction for me in the Balanchine piece, Symphony in Three Movements. She had the central, andante movement, which she danced with Adam Bull. Technically she was quite outstanding. Her extensions took the breath away, and her turns were spectacular. But it was her musicality that stood out. She brought out the changing rhythms and the jazzy overtones of Stravinsky’s score not just in her way of moving but also in her facial expression. She was a delight to watch. Bull was a strong partner but perhaps a little too tall for Kusch?

Gaudiello also had a leading role in Symphony in Three Movements, mostly partnering Dimity Azoury, and I never tire of watching his approach to partnering. He is so attentive to his ballerina in a way that is rarely achieved by others, but he manages at the same time to perform as an outstanding artist himself. Miwako Kubota and Brett Simon danced the third of the leading couples and the corps, wonderfully rehearsed as ever by Eve Lawson, showed off Balanchine’s choreographic patterns to advantage.

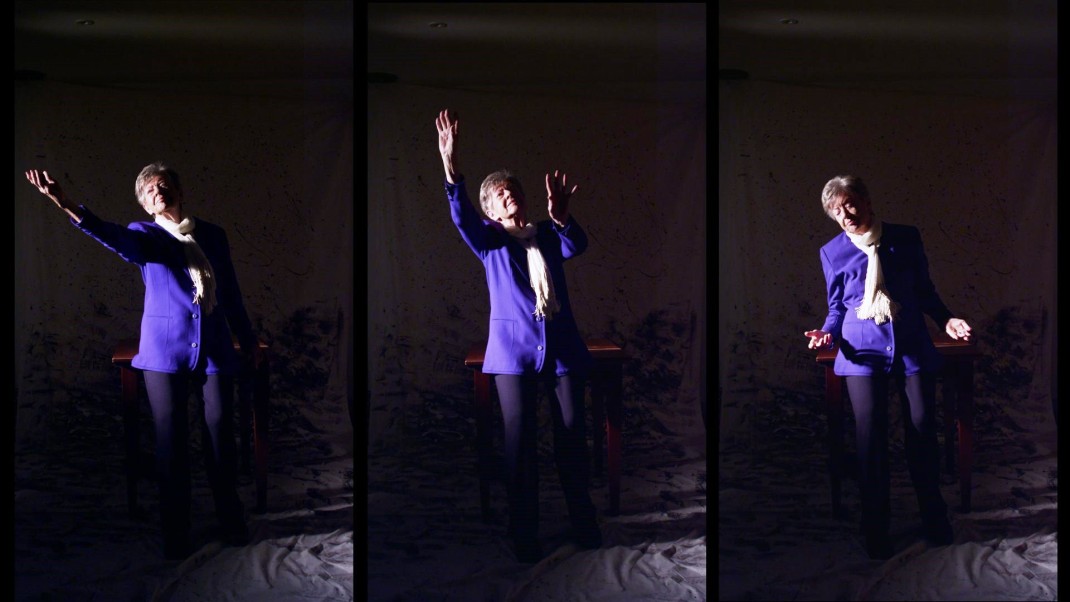

Tim Harbour’s Filigree and Shadow was again strongly danced but, as before, I saw little in it that was substantial enough to excite the mind or eye. It is admirable that the Australian Ballet is exploring new choreographic ideas of course, and large sections of the audience were thrilled with what they saw, but I am still not sure where Harbour was trying to take us.

Michelle Potter, 16 November 2015

My review of 20:21 in Melbourne is at this link.