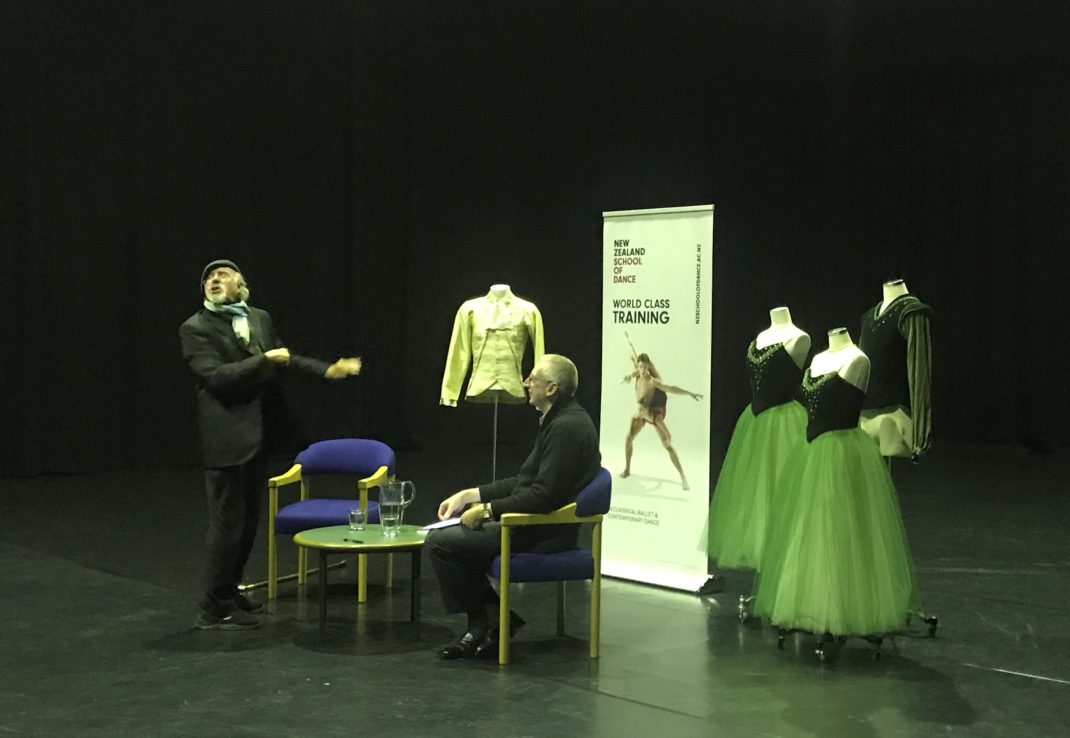

14 March 2025. St James Theatre, Wellington

What is ballet?

In what was a joint program of four works, two from Royal New Zealand Ballet (RNZB) and two from Scottish Ballet, I imagined there would be some curiosity from audience members (or some people anyway) about the nature of ballet. I certainly was curious. Both companies have the word ‘ballet’ in their name for a start, but the details of the program sounded unusual.

Opening the program was Schachmatt (Checkmate in English translation) from Spanish/international choreographer Cayetano Soto, who was also responsible for the set, costumes and lighting. The work was based, notes tell us, on Soto’s admiration for and interest in the songs of people such as Joan Rivers as well as the choreography of Bob Fosse.

There was an exceptional, short and shadowy opening sequence. It was attention-grabbing and at first some of the dancers towards the back of the group looked almost like shadows rather than people.

But as the lighting became less shadowy, we could see the cast dressed in light blue-grey costumes, wearing black stockings that at first looked like knee-high boots, and with black caps as head gear. They danced often with the pelvis pushed back so the spine never looked straight; with arms often making geometric shapes; and with emphasis on hands often stretched flat; and with fingers twisted and curled. The dancers’ movements were fast and furious and bodies were bent and twisted. It made me think how different the movement was from the technique we assume is balletic. It seemed like a quirky novelty rather than a ballet. In fact the whole thing looked anti-balletic to me, although nothing could take away from a powerful performance from every dancer.

Schachmatt, which received an exceptional audience response at its conclusion, was a short piece, just 20 or so minutes, and was followed by a brief, spoken introduction from the stage by RNZB’s Artistic Director, Ty King-Wall, who was accompanied onstage by Director of Scottish Ballet, Christopher Hampson, dressed in a Scottish-style kilted outfit.

After thinking constantly during the unfolding of Schachmatt, especially about choreographic expression and its relationship to balletic concepts, it was an exceptional experience to watch the second item on the program, Prismatic from RNZB Choreographer in Residence, Shaun James Kelly. Kelly played with movement without removing so many balletic essentials as seemed to happen in Schachmatt. Kelly’s choreography showed fluidity; detailed interaction between dancers without that interaction being frenzied; smooth and curving shapes from the arms; lifts that were quite spectacular and that demonstrated a remarkable manner of moving through space; and a great use of the stage area, often in unexpected ways.

We were watching a particular choreographic voice, but one that was not removing what makes dance balletic. Prismatic gave me goose bumps and it was a pleasure to watch the dancers performing to an audience, to us. That’s a personalised approach and was not something I got from the first item. To me Prismatic was theatre.

After interval we watched another short work, Limerence, this time from Annaliese Macdonald, former dancer with RNZB, now freelancing. Performed to music by Franz Schubert, it was made for four dancers who interacted with each other, displaying different emotions at different times.

The leading role was danced strongly by Joshua Guillemot-Rodgerson but we were never completely sure of exactly where his emotions were directed. What was he thinking? What were the others thinking as well, especially when they were trying to guide him through an event? In fact, a quote from Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke was written in the program notes: ‘Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final.’ That quote gave a strong indication of the nature of Limerence.

Choreographically Limerence had a beautifully strong contemporary feel but it was clearly based on an understanding of balletic technique. The bodies of all four dancers were used as expressive tools to transmit emotions.

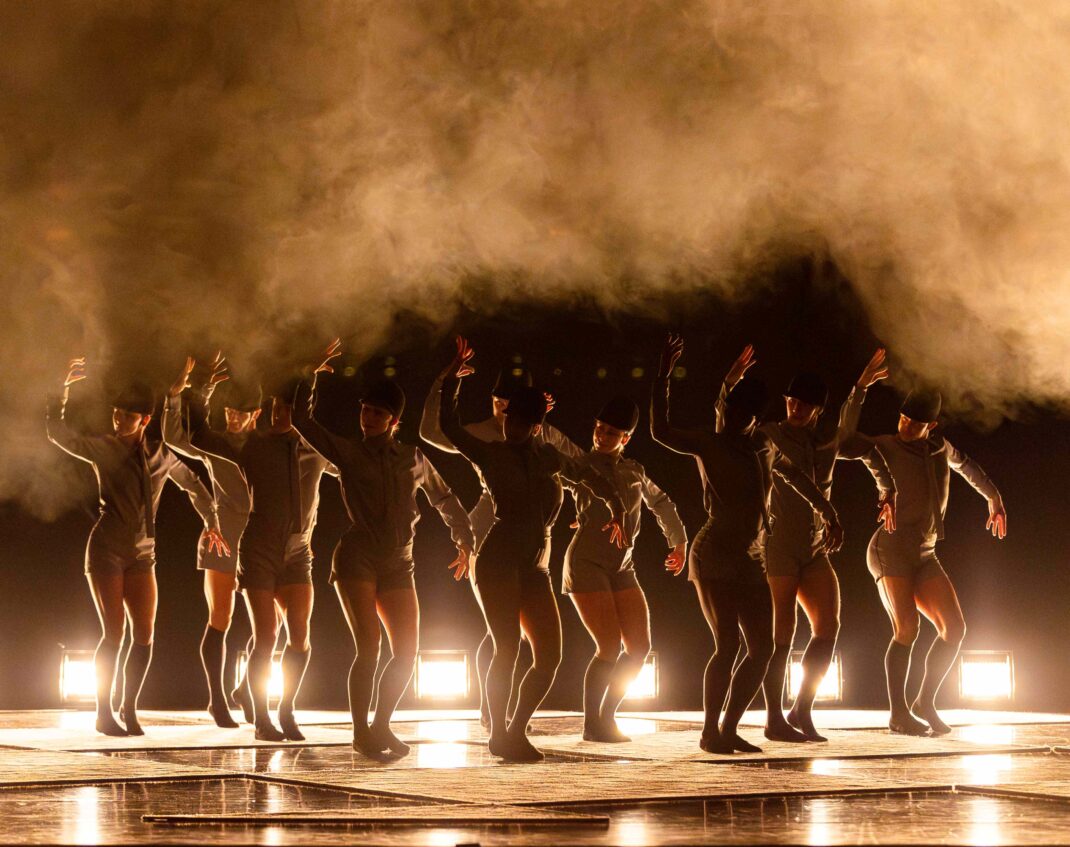

The final work Dextera (a play on the word ‘dexterous’) came from Franco-British choreographer Sophie Laplane. It was danced by a large cast to excerpts from various compositions by Mozart. Laplane mentions in program notes that she was interested in ‘portraying the complexity of human nature through dance’ and complexity of movement (large and small, individual and group) was clearly on display.

Red gloves were a feature. In the beginning one fell through the air from the flies. Then dancers entered, all wearing red gloves. Sometimes one set of dancers ripped the gloves away from the group wearing them. The gloves were then ripped back. In the final moments a swathe of gloves fell again from the flies. I am assuming that the gloves referred to the fact that dexterity usually indicates skill involving the hands.

Another feature of Dextera was that red ‘handles’ had been added to some costumes and dancers (mostly the women) were picked up, (mostly by the men) using the handles, and the bodies manipulated in some way.

Choreographically Dextera teetered towards seeming suitable for inclusion in a program by a company with the word ‘ballet’ in its name. It was clearly pushing movement boundaries but, at least to me, the dancers looked like human beings and the choreography looked as though there was a balletic background that was being used in the ‘pushing’. But the work seemed so long, which was not made to feel shorter when many sections of the work appeared not to relate to each other. I was relieved when the work eventually concluded.

The outstanding feature of the program, over all four works, was the strength of the dancing. Whatever movement ideas the choreographers chose to investigate, the dancers rose to the challenge and performed with gusto. And all my congratulations to the staff of both companies for creating a program that put forward a challenge. In fact, as I left the theatre I had the feeling that it would be hard to find a performance that could give rise to so many varying thoughts about the nature of ballet.

.Michelle Potter, 16 March 2025

Featured image: Scottish Ballet dancers in a moment from Sophie Laplane’s Dextera. Photo: © Andy Ross

UPDATE: This post has been the subject of a series of scam messages and comments have, therefore, been closed.