This is a slightly edited version of the text and PowerPoint images for a keynote paper I gave at the 2022 BOLD Festival in Canberra on 3 March 2022

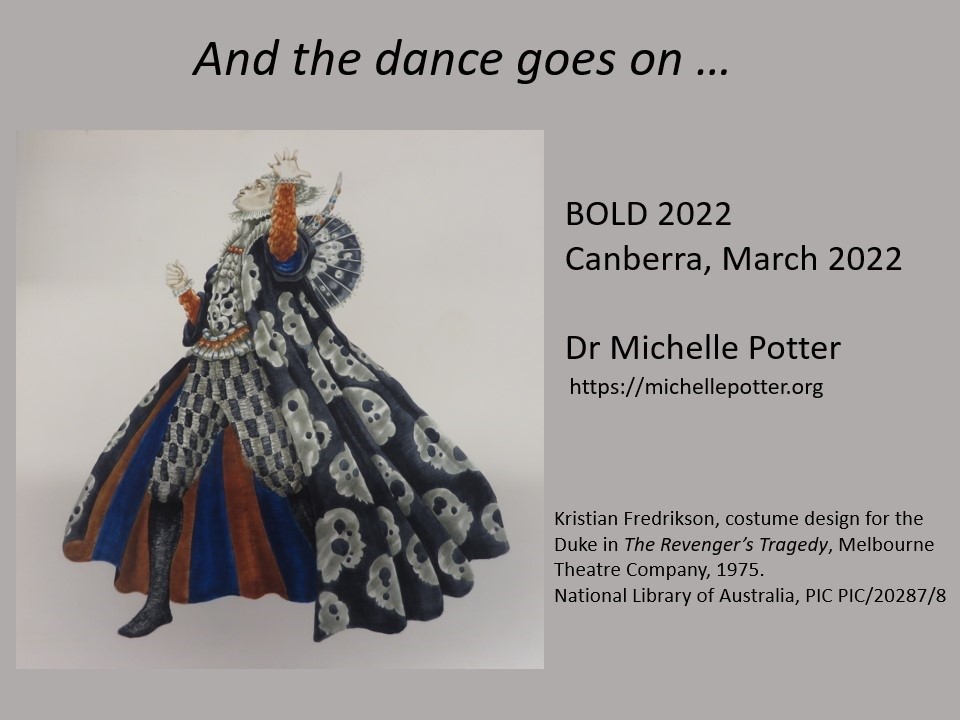

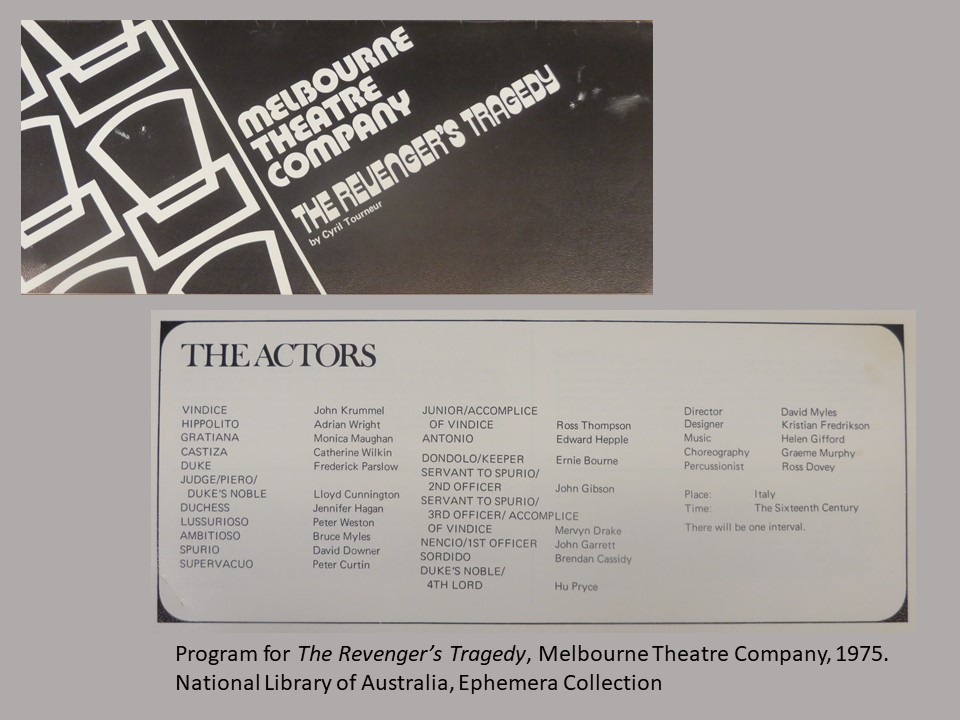

Looking at the opening slide for my talk this morning you may be wondering why, for a keynote talk at a dance-oriented festival, I have chosen an image from a theatre production, Melbourne Theatre Company’s 1975 production of The Revenger’s Tragedy. And perhaps you may be curious as to why I have given it the title ‘And the dance goes on.’ All should, I hope, become clear as we proceed.

But first take a good look at Kristian Fredrikson’s costume design for the Duke in The Revenger’s Tragedy in the slide above. Fredrikson was an exceptional designer and an artist really. No stick figures for him. His designs were drawn as if they were being worn by the particular character in the play, film, dance, opera, or whatever theatrical genre he was working on, and he worked across them all. He did a huge amount of research, and collaboration, before designing and had in his mind a very clear picture of the nature of each particular character. Not only that, his designs are filled with movement, both body movement and the potential movement of the costume. Take a look at the way he has positioned the Duke’s head, thrown back and assertive. Look at the way he has drawn the legs, well-separated as if in movement. Then there are the expressive arms and hands. He has also drawn the costume spread out well —partly of course to show details of the design but also to indicate how the costume, especially the cloak, would move as the Duke strode across the stage. This design will be on show in the National Library’s exhibition On Stage, which opens tomorrow. I encourage you to visit the exhibition. I hope the backstory, which I will discuss shortly, will make seeing the design especially interesting.

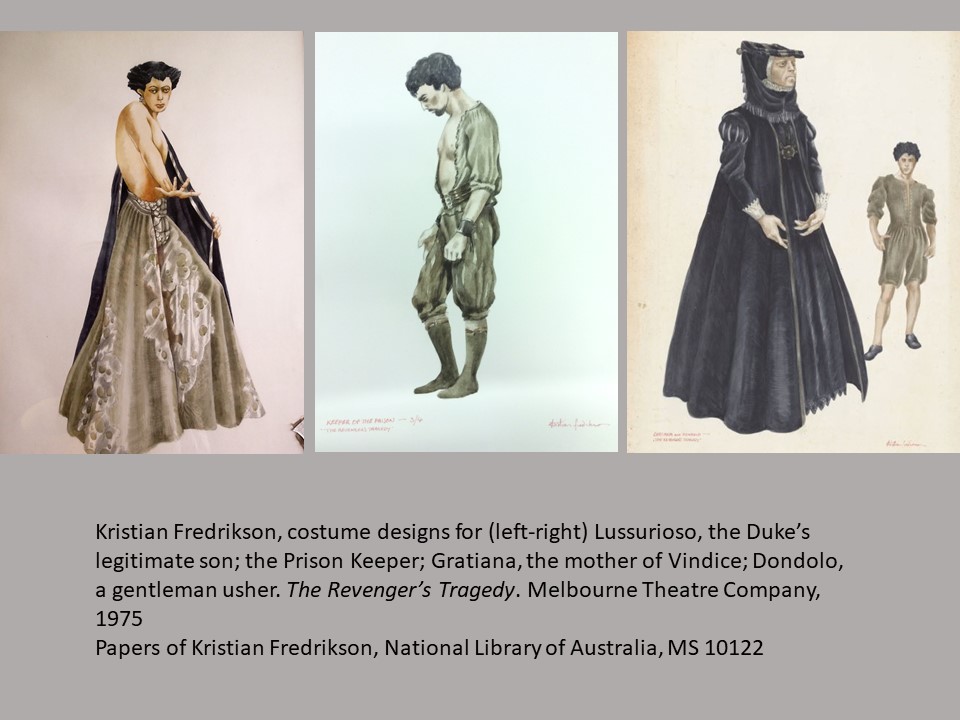

On this next slide here are three more costume drawings from the same play, The Revenger’s Tragedy. These are not part of the exhibition but are part of the National Library’s exceptional collection of Fredrikson material, and my talk will focus to a large extent on the National Library’s collections of various materials, including Pictures, Manuscripts, Oral History and Ephemera.

You can see, left to right, Lussurioso, whom one writer has called a ‘lustful jerk’ and who is the Duke’s legitimate son; then the Prison Keeper; then Gratiana, who is the mother of the revenger. I think you can see again an interest in movement in the designs, as well as expressiveness in the way the characters are drawn.

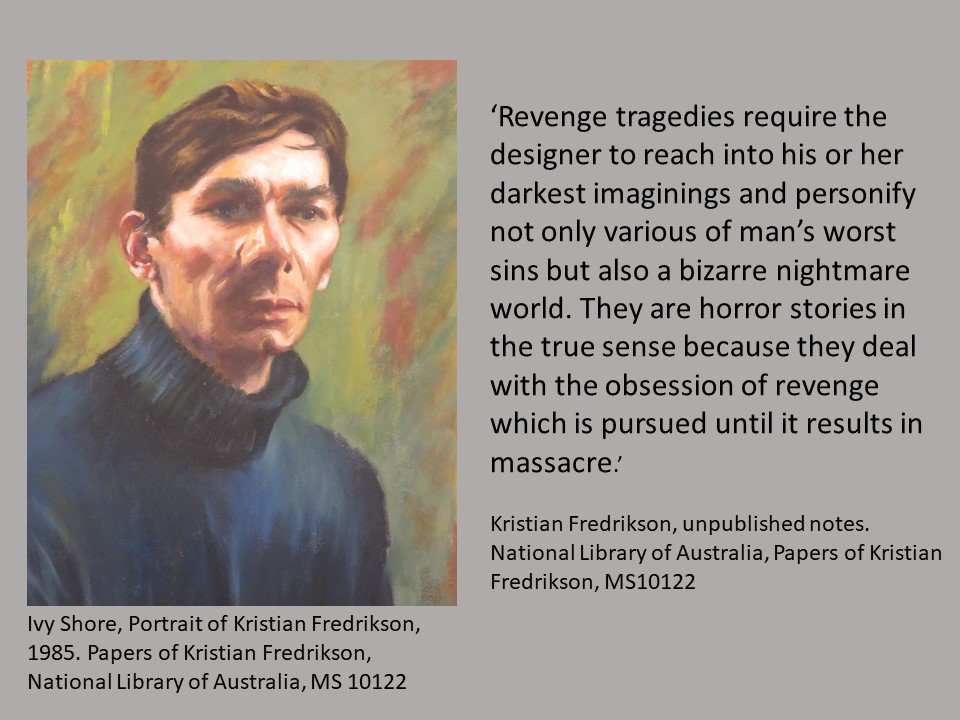

The Revenger’s Tragedy is a Jacobean play dating to the very early seventeenth century. It was first performed in London in 1606 and there has been much academic discussion over the years about the author, but the latest understanding is that it was written by one Thomas Middleton. The play centres on lust and ambition in an Italian court and the Revenger of the title, whose name is Vindice, seeks revenge on the Duke for poisoning Gloriana, the woman he loves. This happened several years before the play starts but Vindice has been mulling over it for years. In a convoluted series of events the Duke is poisoned and then stabbed by Vindice. But the Duke’s successor, Lussurioso, is also killed and eventually Vindice is condemned to be executed. This is a very simple outline but you will understand the extent of the killings when I tell you that one reviewer of the Melbourne Theatre Company production wrote: ‘It opens with a bloodcurdling shriek accompanying a tableau vivant and closes with an ironical shrug and a pile of dead bodies.’ As an example of his involvement in works he was designing, Fredrikson wrote his own notes about revenge tragedies, and at one point said: ‘Revenge tragedies require the designer to reach into his or her darkest imaginings and personify not only various of man’s worst sins but also a bizarre nightmare world. They are horror stories in the true sense because they deal with the obsession of revenge which is pursued until it results in massacre.’

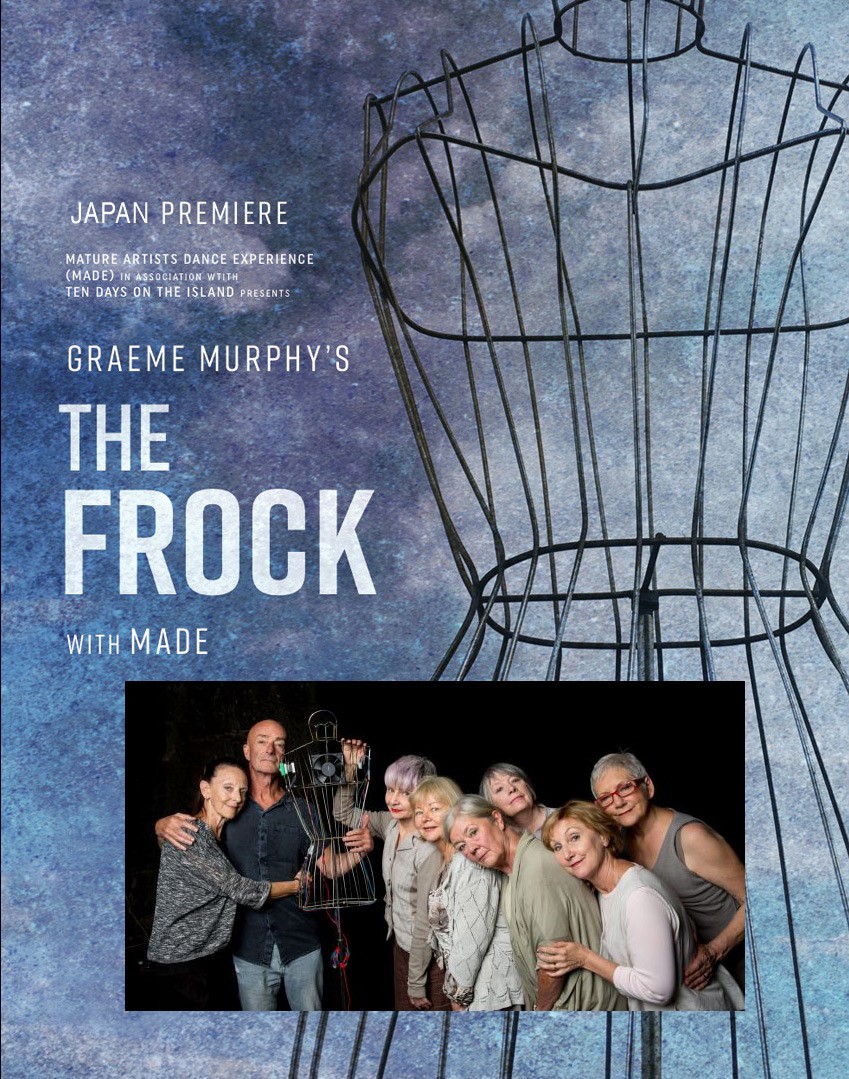

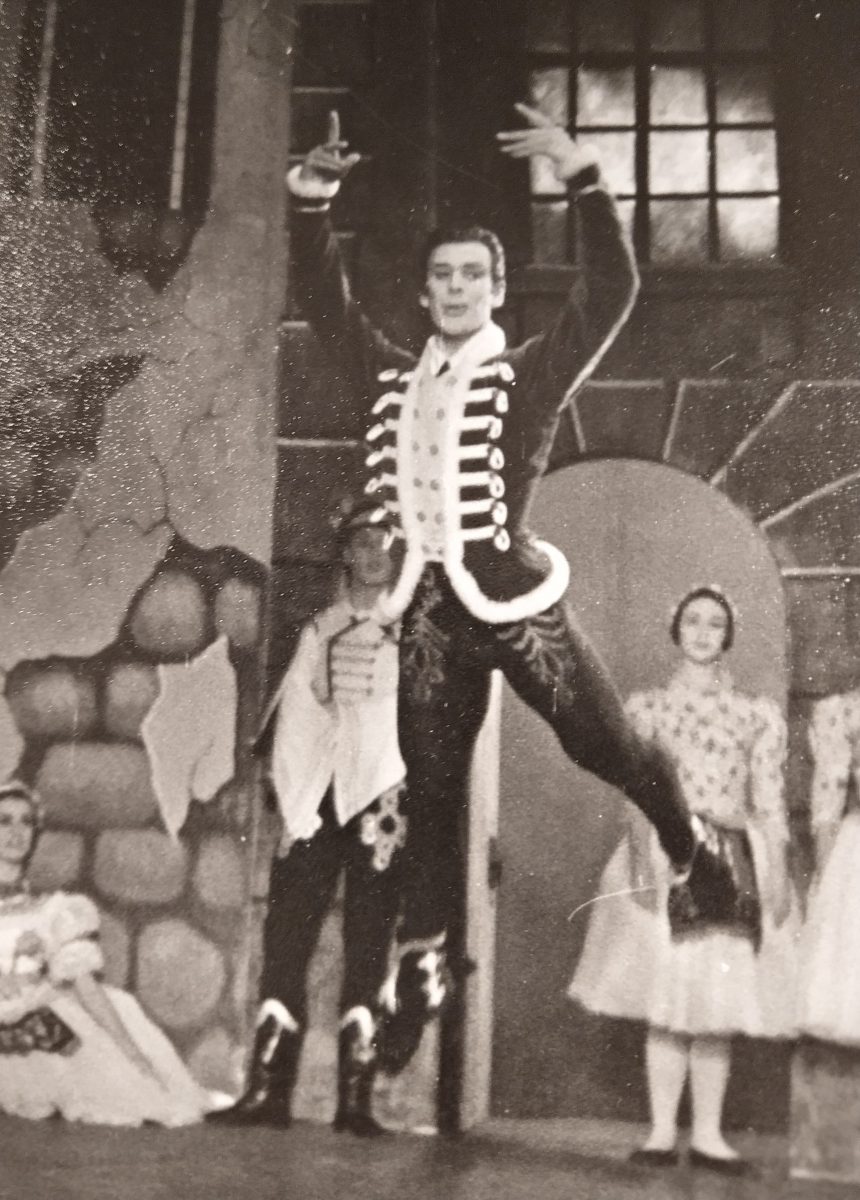

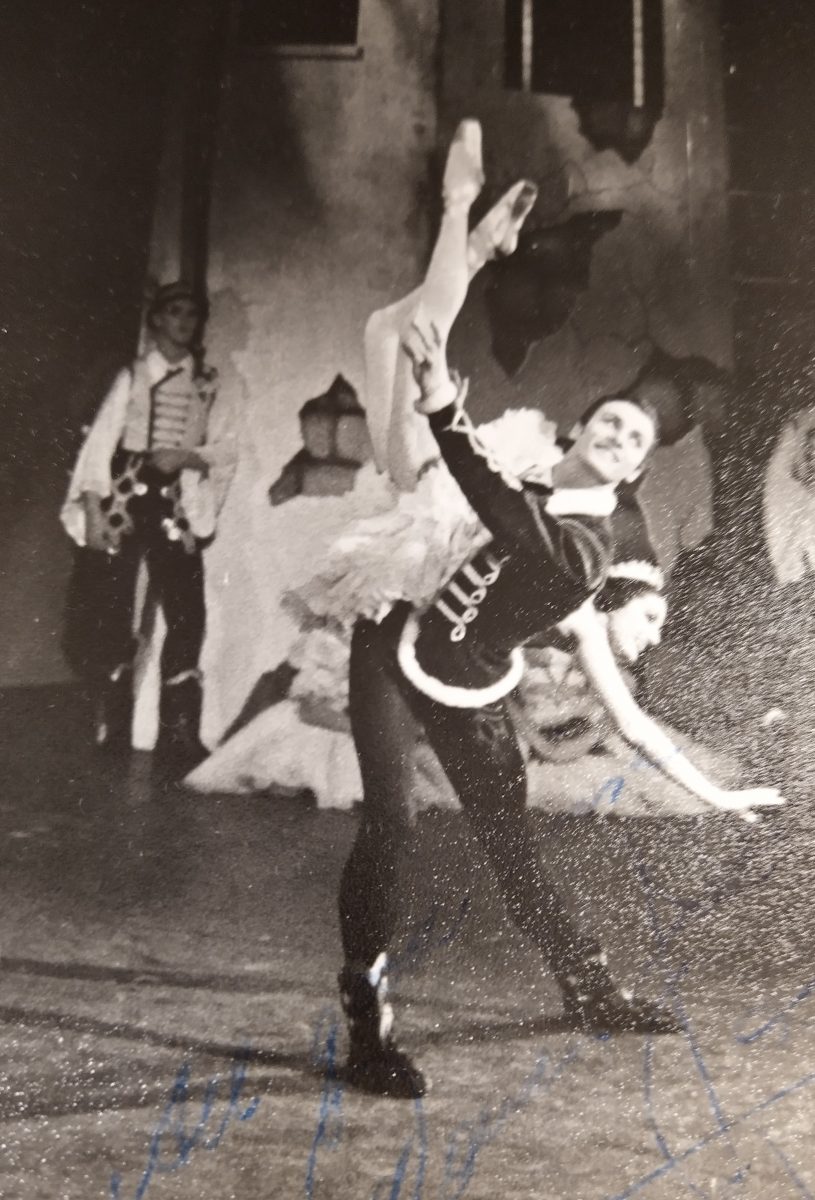

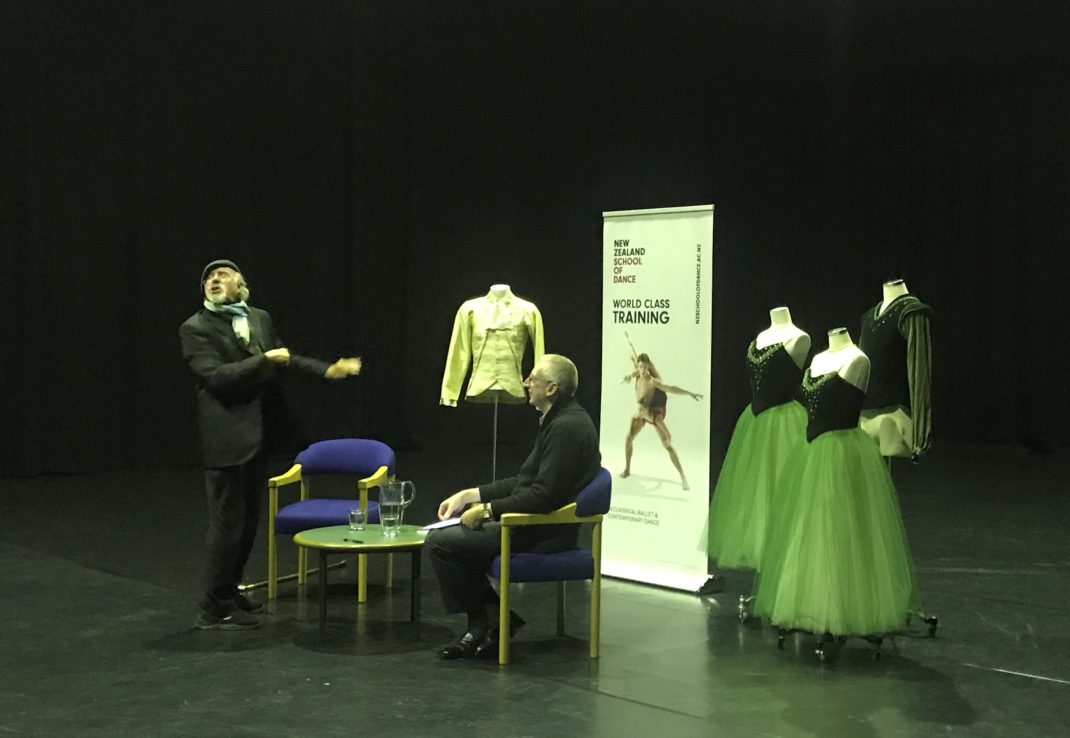

It is probably not surprising to anyone here that a genre called ‘revenge tragedy’ ends in tragedy! But this Melbourne Theatre Company production had a surprise outcome and that outcome went on to have long-lasting effects on the growth of dance in Australia. The show was directed by David Myles, an Australian who began his theatrical career in television before heading to London, making a career there and across Europe. He returned to Australia in the 1990s but in 1975 he was in Australia as a guest director for Melbourne Theatre Company. The final orgy scene of The Revenger’s Tragedy needed a choreographer to give it an orgiastic feeling and it was none other than Graeme Murphy who was commissioned to create that scene. Graeme had returned to Australia in 1975 after spending time in Europe, in particular with the Ballets Félix Blaska in Grenoble, France. He and Janet Vernon spent 1975 freelancing before joining the Australian Ballet again in 1976.

I’m going to play you now a brief audio clip from an oral history interview with Kristian Fredrikson, who explains a little about what happened with the choreography.

He makes an error or two in this clip, saying that Graeme was a student or dancer with the Australian Ballet when he was brought in to work on The Revenger’s Tragedy. But, as I have just mentioned, Graeme was actually freelancing in 1975. Fredrikson also doesn’t remember, on the spur of the moment, the name of the director, which I have mentioned was David Myles. Here is how Fredrikson describes what happened.

It is more than interesting to hear him say that the director threw out Graeme’s contribution, but Fredrikson’s memories may be a little exaggerated. A conversation I had with Graeme while I was writing my biography of Fredrikson indicates that much of what he choreographed did become part of the production, and, as you can see from the image below, his name appears as choreographer on the printed program for The Revenger’s Tragedy. But apparently it was not a smooth process. Notice too that the playwright’s name is given as Cyril Tourneur although, as I mentioned scholars now believe that the playwright was Thomas Middleton.

Now, despite the ‘pile of dead bodies’ with which the play closes, and the apparent difficulties David Myles may have had with the choreography, the meeting of Murphy and Fredrikson was a momentous one. While both would pursue independent careers over the years, they would also constantly team up in major collaborative endeavours for a number of theatrical organisations.

As I have mentioned, in 1976 Murphy rejoined the Australian Ballet as a dancer and as the company’s first resident choreographer. But at the end of the year, he was appointed to head the Sydney-based Dance Company (NSW), later to be renamed by Murphy as Sydney Dance Company. Shortly after taking up his appointment, he called Fredrikson, and much to Fredrikson’s pleasure and surprise, offered him a commission to work on a new ballet he was planning, a production of Shéhérazade, not to the well-known score by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov as famously used by Diaghilev for his Ballets Russes, but to a song cycle by Maurice Ravel.

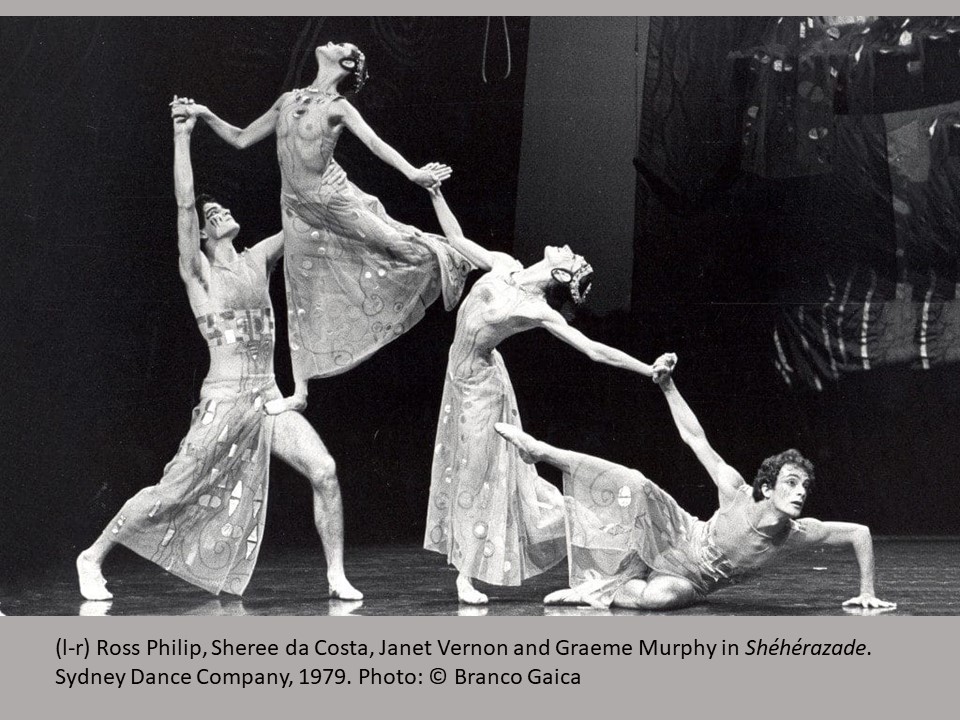

Shéhérazade, which premiered in Sydney in 1979, was, in my opinion, one of the most stunning of the works Murphy made early in his career with Sydney Dance, not only from a choreographic point of view, but also in terms of the collaborative endeavours created together by Murphy and Fredrikson. It certainly got the collaboration off to a good start. Above is an image from the original 1979 production in which both Murphy and Janet Vernon danced.

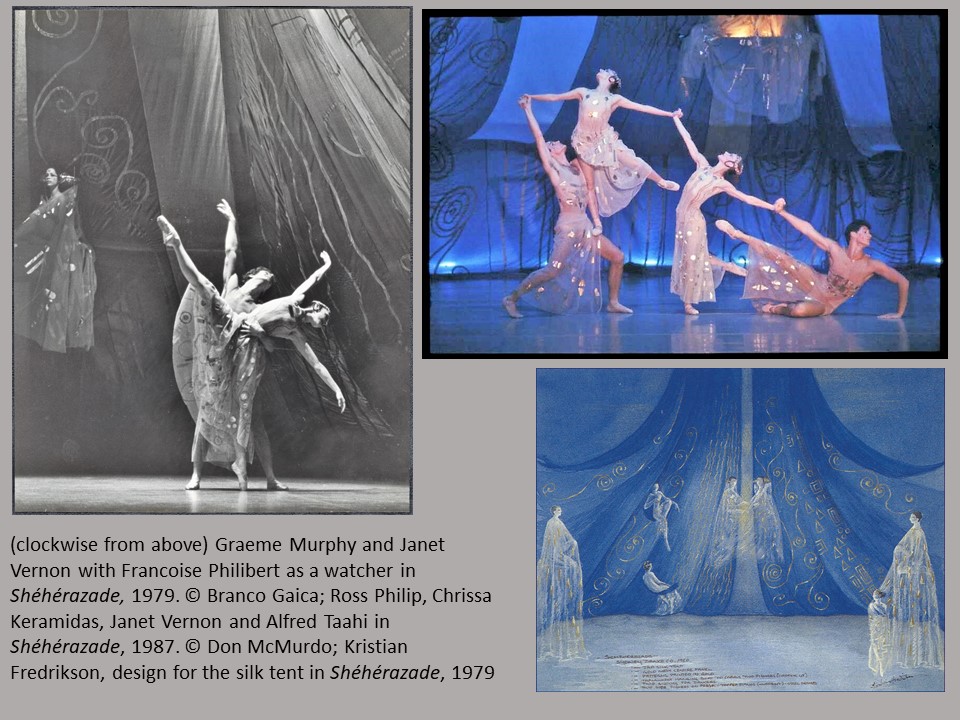

Shéhérazade was an incredibly erotic work. Brian Hoad, who was dance critic for the now-defunct magazine The Bulletin, called it ‘a choreographic mood painting at its most luscious…it turns out to be one of the most thoroughly bewitching evocations of sensuality ever to grace a stage.’ In the background you can see a hint of lighting and a backcloth and I want to show you the backcloth in more detail and the colour that was involved.

The backcloth was like a tent and four dancers, the Watchers, sat suspended in it. You can see one in the image on the left. They watched the dance unfold below them and shielded their eyes when matters got too erotic. The colour scheme was blue and gold and you can see a design for the tent bottom right of the slide. It’s now part of the National Gallery of Australia’s collection, while the two photographic images are part of the National Library’s collections. I’ll play you another audio clip from the Fredrikson oral history in which he talks about designing Shéhérazade. You’ll hear him mention that Gustav Klimt, whose art work, made in Vienna in the early twentieth century, was his inspiration. But also interesting is the way he speaks about the collaboration. ‘Shéhérazade came about in an easy flash’ he says.

So, a result of The Revenger’s Tragedy one spectacular aspect of dance in Australia was born, a collaboration between a choreographer and a designer that resulted in some sensational works over three decades for Sydney Dance Company, the Australian Ballet, and Opera Australia.

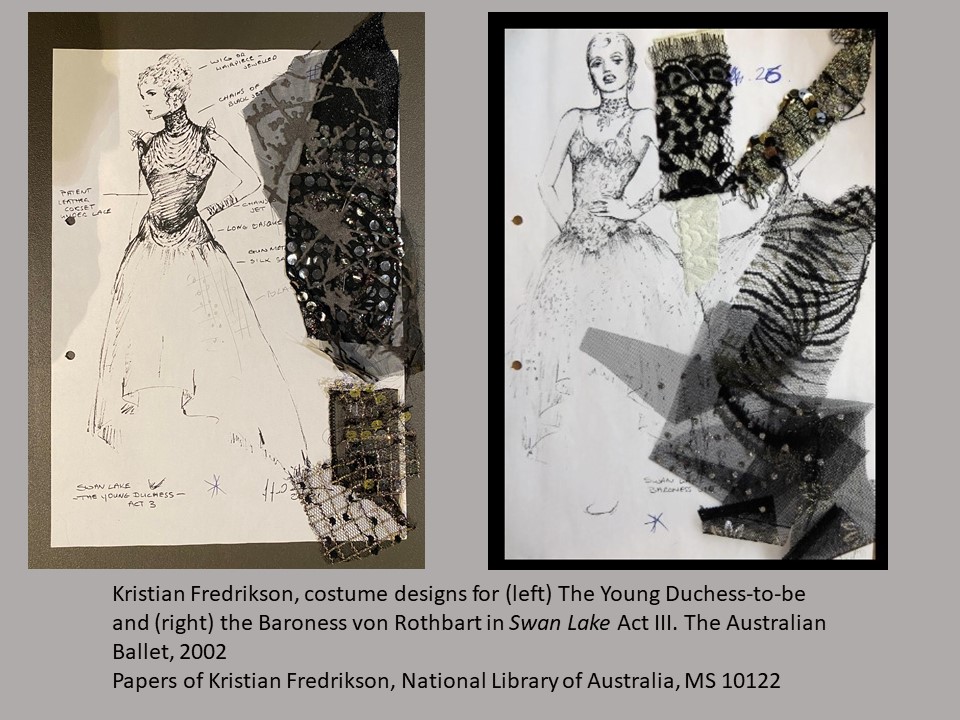

Now, there are more designs in the On Stage exhibition that record the Murphy/Fredrikson collaboration, including one or two for Swan Lake and Nutcracker: The Story of Clara. I’m going to focus on Swan Lake, which premiered for the Australian Ballet in 2002.

The Murphy Swan Lake is quite a change from what many had come to see as the ‘normal’ version. The narrative follows the tragic story of a young, vulnerable woman, Odette, who yearns for the loyalty of husband-to-be, Prince Siegfried, but who discovers on the eve of her wedding that Siegfried has a lover, the seductive and possessive Baroness von Rothbart. That discovery marks the beginning of Odette’s mental decline, which takes place in Act I, following the wedding. In Act II Odette is confined to a sanatorium after Siegfried’s mother, a cold and dismissive Queen, calls a doctor towards the end of Act I to attend to Odette’s apparent illness. In the sanatorium Odette is attended by nuns and, at one stage while there, she rocks rhythmically backwards and forwards in a dazed state and has a vision of white swans and a frozen lake. In a scenic transformation we are transported to the lakeside where Odette dances with the swans of her imagination and, meeting Siegfried there, she performs a duet with him. Later she leaves the sanatorium and in Act III arrives at a glittering party hosted by the Baroness and Siegfried. But, although Siegfried ultimately rejects the Baroness and regrets his behaviour towards Odette, Odette believes she can never find peace and in Act IV drowns herself in the lake of which she has dreamt in Act II.

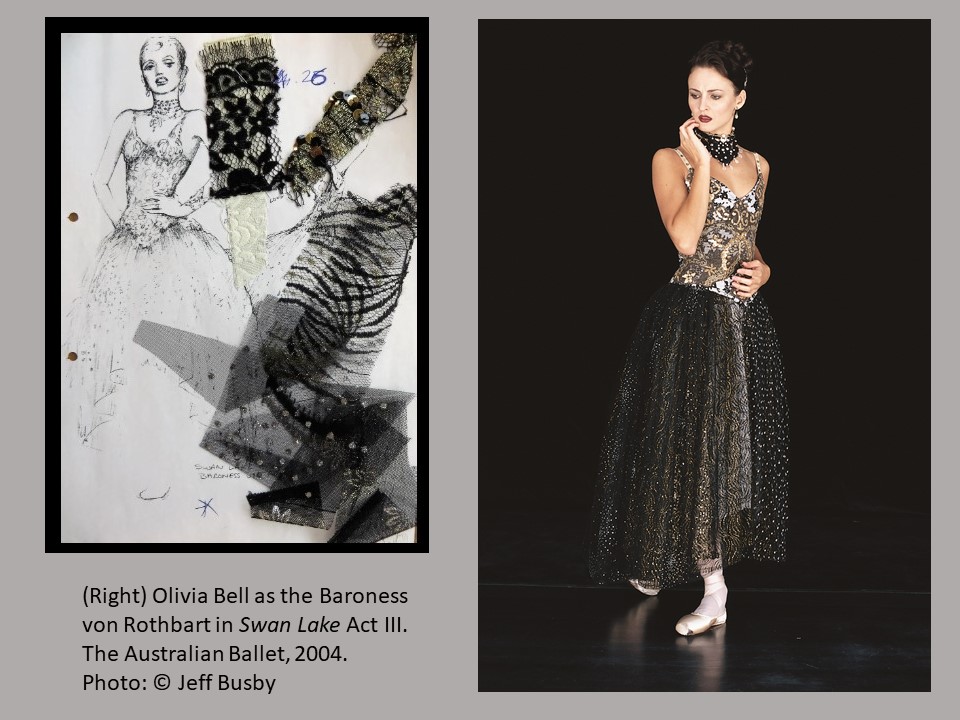

The image on the left on the slide above is a design that you will see in the exhibition from tomorrow onwards. It is for ‘The young duchess’ (or ‘The Young Duchess-to-be’ as she was eventually called when the work went on stage). The costume is what she wore to the ‘glittering party’ hosted by Siegfried and the Baroness in Act III. You can see that it is not so much a work of design art, but a practical drawing that would be used by the wardrobe department when making the costume. It’s interesting to see an Edwardian style in parts of that costume, especially in the high neck and the draped, low-slung bodice. Fredrikson wanted to set this Swan Lake in the Edwardian era, although not every costume had all that much that was recognisable as Edwardian. On the right is a design for the Baroness von Rothbart in Act III, also for the ‘glittering party’—without many Edwardian references, I think. And here is what the Baroness’ costume looked like when made up.

But what is interesting about this Swan Lake is that by this stage, 2002, Fredrikson had become more than a designer for Murphy. They had set up a relationship that went beyond things coming ‘in an easy flash’, as Fredrikson had mentioned in relation to Shéhérazade, to one where Fredrikson had become an essential member of the creative team. He replied by email at one stage to a request from a journalist for information about Swan Lake with these word (and unfortunately I can’t play them as audio since they were written rather than spoken):

‘The actual inspiration for this production came about at our (Graeme, Janet and myself) first brainstorming meeting to see in which direction we wished the story to go so that it would please not only us, but also have an emotive and comprehensible value for the audience. For some time we considered manipulating the tragic story of the imperial family of the Romanovs … but soon discarded this as needing too much distortion to fit the score. Then, secondly, we were well versed in the history of the first production of the ballet and the bitter rivalry between the two ballerinas who first played Odette. This seemed promising as a scenario, but after an amount of discussion we were discouraged by the problems of conveying the romance of the original story. It was Janet who first brought up the obvious fact that this ballet was about Royal Romance and its ultimate despairing failure … So this was our beginning and, although we were determined that this would be no biography of any one particular Royal duo, we would have much material to supply us for Tchaikovsky’s tragedy.’

So, Fredrikson was totally part of the development of the story as well as the designer of sets and costumes. Fredrikson died in 2005 and Swan Lake was his last collaboration with Murphy.

That collaboration had grown and developed over almost three decades and gave the dance world some spectacular productions. And it all began with The Revenger’s Tragedy. My title for this talk … ‘And the dance goes on …’ alludes to the ongoing and developing relationship between Murphy and Fredrikson.

*************************

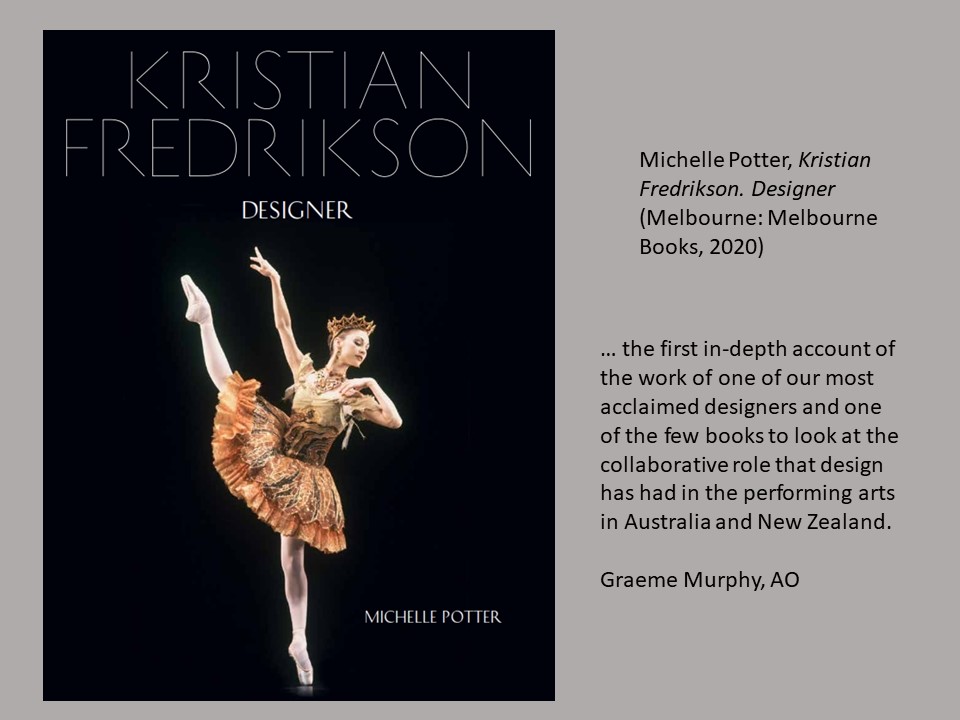

Thank you for coming (or watching if you are online) and I hope you will take the opportunity to visit On Stage, which continues until 7 August, and will find particular enjoyment in looking at the designs by Fredrikson for Murphy productions. There are one or two more that I haven’t had time to discuss. I hope too you might be interested in reading more about the Murphy Connection in my recent book Kristian Fredrikson. Designer. Chapter 4 is in fact called ‘The Murphy Connection” although the beginnings of the connection form part of Chapter 3, ‘Into the Seventies’.

Michelle Potter, 8 March 2022