17 & 18 August 2018. Opera House, Wellington

Reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The Royal New Zealand Ballet’s Strength & Grace program consists of four choreographies by women invited to mark the 125th anniversary of women achieving suffrage, with Kate Sheppard and her many New Zealand followers having led the world in that. It’s Sheppard’s face on our $10 bill, she is honoured in many parts of the country, particularly Christchurch her home town, and is considered by many to be New Zealand’s second most influential person, so a good choice by RNZB to allow choreographies to grow from her inspiration.

Overall, each of the four works has considerable strengths, but it is the dancers’ outstanding performances of commitment and calibre that made the night. I consider one of the works would be a true standout in any context or themed season, but each of them will have appealed to one section or another of the audience. It was in fact easy to find colleagues and friends, both younger and older, who had chosen a different favourite. Thankfully it is not a competition.

The first piece, So To Speak, by American choreographer Penny Saunders, explored the domestic relationships within a family. Kirby Selchow and Loughlan Prior, as Mother and Father, used striking gestures of clarity and fine timing in a highly effective opening motif, around a table downstage left, though the work became somewhat diffused when a large chorus-like cast entered. The use of pointe shoes for the Mothers but soft shoes for the Daughters, with close to identical dress for both generations of women, were subtle design choices lost on many I suspect. Dramatic opportunity to express the tensions between parents and children was lightly referenced, but the music of four different composers made for a somewhat meandering choreographic structure. Nonetheless the work made its mark and the performances were strong.

The second piece, Despite the Loss of Small Detail, by New Zealander Sarah Foster-Sproull, was sharp and spunky, and held great appeal for younger audience members. Eden Mulholland provided a lively percussive accompaniment, and the strength of movement delivered by the dancers certainly matched it. Abigail Boyle was a compelling central figure, supported by a somewhat enigmatic group of dancers. One memorable sequence had them stabbing the stage using pointe shoes as weapons, in a trope reminiscent of Akram Khan’s recent Giselle. The fashion-led design choice of costuming brought whimsy to what was nonetheless a serious declaration of independence.

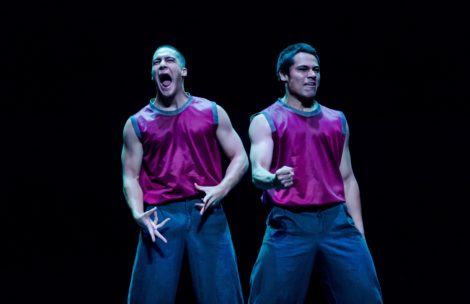

The third work, Remember, Mama, by Australian Danielle Rowe, was to my mind the clearest work overall in both structure and theme. Although it also used four different composers, there was a distinct adjustment within the choreography at each section which made for welcome coherence to its unfolding. Nadia Yanowsky gave a strongly felt performance as The Mother, relating to The Son at various ages played by three different dancers. Shaun James Kelly always dances with quality and was a sparkling delight as the young child, using Mozart’s Ah! Vous Dirais-je Maman to great effect. Fabio lo Giudice was a sultry teenager, but Paul Mathews danced the adult son with a deep empathy and tenderness for his mother that will have touched many. He is a dancer with the intuition of an actor for how to portray character, and is one of the company’s real strengths. The group of men seemed like soldiers lost to the call of war, perhaps. The group of women fought as hard as any soldiers.

The fourth work, Stand to Reason, by South African choreographer Andrea Schermoly, took as reference one of the pamphlets Sheppard had produced in her stalwart campaigning years, projected as text behind the dancers. (That raised laughs among the audience but would have seemed anything but comic 125 years ago). Of the three composers used, the richest and most eloquent dance music of the whole evening was the Folie d’Espagne of Marin Marais, in a recording by Jordi Savall (the highlight performer of Wellington’s Arts Festival earlier this year). That drew a strong response from the cast of eight women, with particularly galvanised and striking performances from Mayu Tanigaito, Madeleine Graham and Kirby Selchow. Despite many standout performances of the program, a following solo by Selchow gave her a true claim to being the dancer of the evening. The work was at its strongest at that point and might well have finished there, in orbit.

So overall, this is a program of strong choreographic ventures, a few unusual costume design choices, and effective lighting throughout by Andrew Lees. There’s a mosaic of different music compositions (12 in all across four works) and I know that can pose a distracting challenge for musicians and music-followers who tend to stay away because of that. Most memorably there is stunning dancing from a pedigree company that is half the age of the Suffragettes’ achievements.

Jennifer Shennan, 19 August 2018

Featured image: Nadia Yanowsky and Paul Mathews in Remember, Mama, Royal New Zealand Ballet 2018. Photo: © Stephen A’Court

Afterthoughts:

The sightlines in the Opera House are quite different from those in the St. James Theatre where the company usually performs, and that needs to be borne in mind for choreographic staging and video projections, both of which were compromised on several occasions. (My two immediate neighbours left at half-time since their view was seriously affected, and the seats were not classed as restricted viewing at the box office). The sound system is also perhaps settling in, and music volumes were at times uncomfortably loud.

This Wellington season of only two performances, and no tour to other centres, has left many dance followers further afield hoping for a future opportunity to see this program. The company website lists “Details Soon” for the Harry Haythorne Choreographic Awards towards the end of the year, now in its fourth year, so they may be planning to attend that season instead. New choreography brings fresh blood, and these stalwart dancers always perform, new work and old, as though lives depended on it. JS