14 May 2025. Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

Having just reread Different Drummer, Jann Parry’s 2009 biography of Kenneth MacMillan, choreographer of the ballet Manon, I was curious to see the Australian Ballet’s production of that work. Would the background that Parry provides in her biography open up the work for me. Well I wasn’t disappointed.

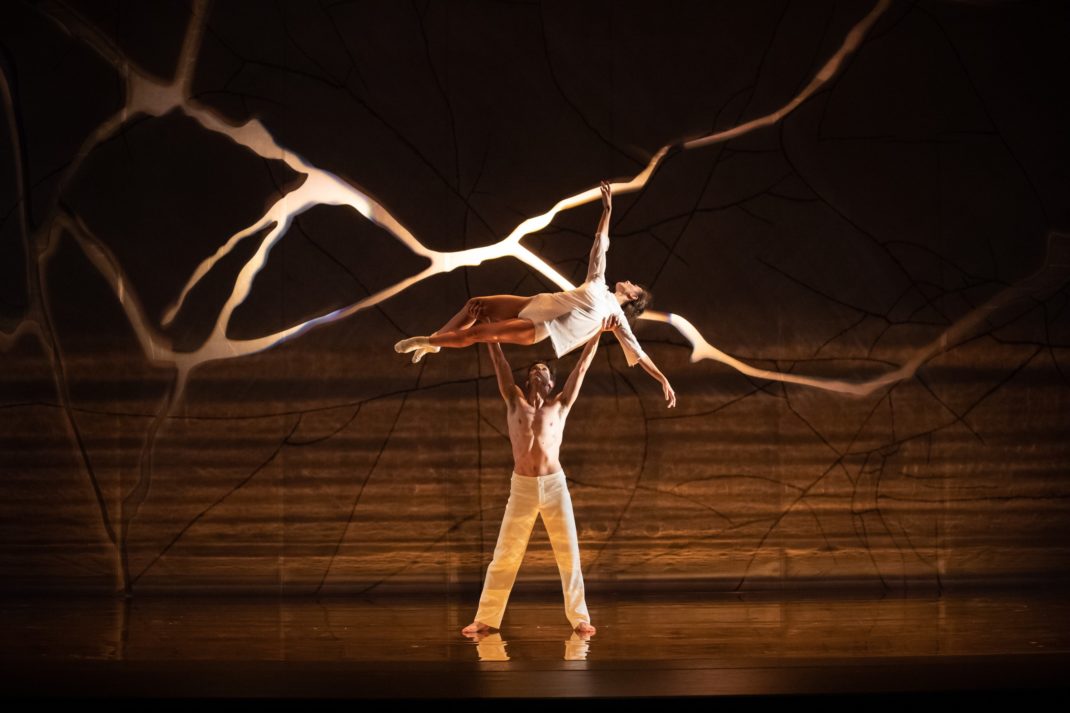

As a choreographer MacMillan is definitely a ‘different drummer’ and it was a particular treat to watch his pas de deux, the format with which, according to Parry, he loved to start work on each new initiative. Although I thought some of the pas de deux in Manon might be considered a little long (the final one in which Manon died in the arms of Lescaut for example), all were spectacular in terms of the connections, physical and emotional, that the choreography set up between whichever two characters were involved. Not only that I was fascinated to watch the tiny details MacMillan put into his choreography. The feet and the hands often took on surprising details, and the pirouettes and tours en l’air from the male dancers often ended in unusual ways that clearly required exceptional technical input. Then there was MacMillan’s handling of groups of dancers, including some quite beautiful moments of canon-style choreography. As a whole, the choreography of Manon is truly masterful.

But who staged the production I wondered? For the choreography to look as remarkable as it did, the work also needed to be staged well and with more than a passing understanding of what constitutes excellence in staging a narrative ballet. It turned out that this production was staged by Laura Morera and Gregory Mislin. Mislin is the Royal Ballet’s choreologist. Morera is a former Royal Ballet dancer whose work I have admired on many an occasion but who is now artistic supervisor for both the MacMillan and the Scarlett Estates. Morera was recently principal coach for Queensland Ballet’s production of MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet, which was staged by Gary Harris. Both Harris and Morera did a magnificent job on that occasion. So I was not a bit surprised when I discovered Morera had staged the Australian Ballet’s Manon. The Australian Ballet’s Manon, like the Queensland Ballet Romeo and Juliet, was completely engaging as a story from beginning to end, as well of course as being fabulously danced by the impressive artists of the Australian Ballet.

At the mid-season matinee I attended I saw Jill Ogai as Manon and Marcus Morelli as Des Grieux, Manon’s (eventual and final) lover. Both danced well, perhaps especially Morelli who attacked the choreography with strength and commitment. But for me the standout dancers were Cameron Holmes as Lescaut (Manon’s brother) and Katherine Sonnekus as Lescaut’s mistress. They both have secure techniques, which allows plenty of freedom to develop characterisation. The acting from both of them was outstanding making it easy for the audience to engage with them. The absolute highlight was their pas de deux in Act II at the party given by Madame X (Gillian Revie) at which Lescaut had had one too many glasses (or bottles) of alcohol. His drunken stumbles, at which the audience fell about laughing, simply made his attack on MacMillan’s demands look even more brilliant. Sonnekus managed to handle beautifully the many incredible lifts that, cleverly, looked like the work of a drunken man but which were definitely MacMillan-esquely balletic.

The music by Jules Massenet was nicely played by Opera Australia Orchestra while Peter Farmer’s sets and costumes evoked well the period and the locations. With all aspects of the production working together so well, the story (which I have not gone into in detail here*) was clear and the two to three hours of dancing was an absolute delight.

I guess my one quibble is that this production really needs a bigger stage than that of the Joan Sutherland Theatre (a common issue of course). There were times, especially in Act I, when there was just too much happening on stage. The activities were being brilliantly handled but there were times when those activities were too close to the main action and were thus distracting from that action to too great an extent.

Despite the quibble, this production of Manon showed MacMillan’s brilliance. Huge compliments must go to Laura Morera and Gregory Mislin for their input in making that brilliance shine through, not forgetting that the dancing was splendid across the board from the dancers of the Australian Ballet.

Michelle Potter, 15 May 2025

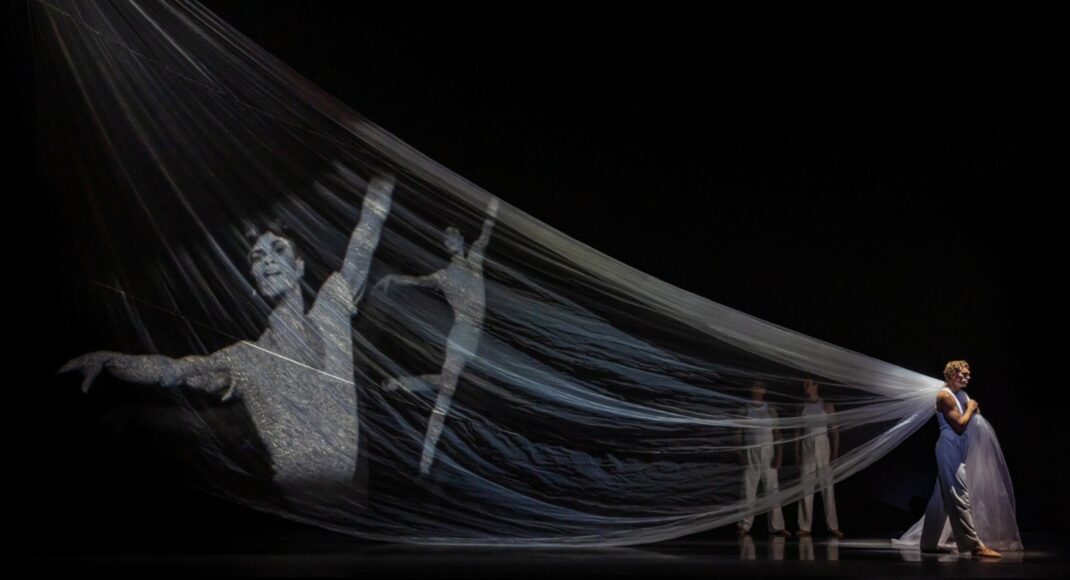

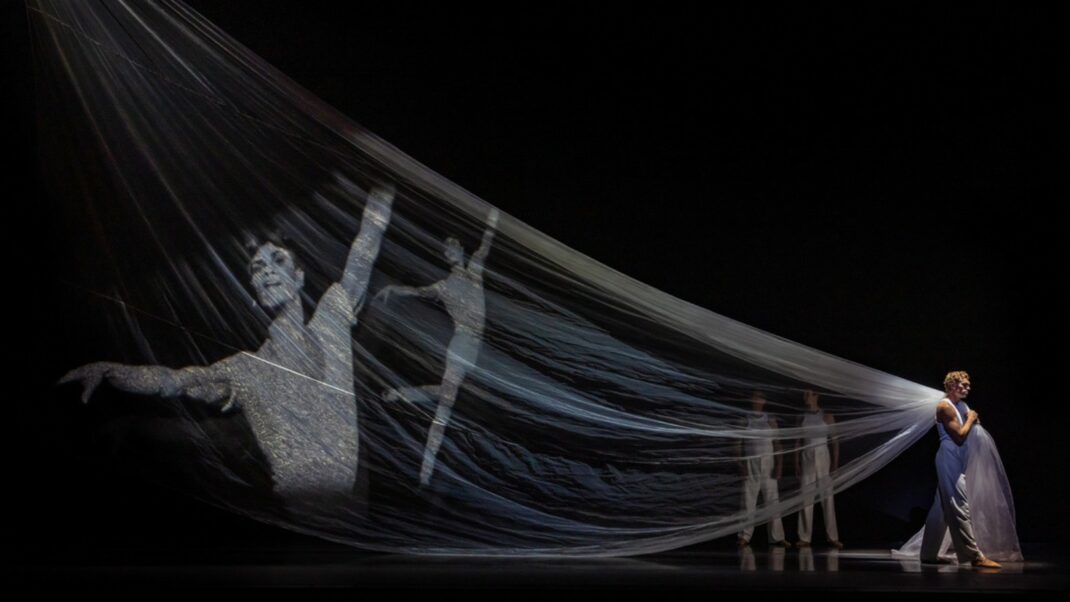

Featured image: Artists of the Australian Ballet in the card scene from Act II of Manon, 2025. Photo: © Daniel Boud

*For a synopsis of Manon see this link.