This year, for the first time in over 100 years, all public gatherings to mark Anzac Day were cancelled, due to the lockdown imposed as part of the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic: an enemy if ever there was one, not war between nations this time but a hope that all countries might join a common fight.

Traditionally Anzac Day commemorations shape up as a kind of countrywide choreography, starting with a Dawn Parade in every city, town, village or marae—a bugle, a salute, a karakia, a march, a haka, a hymn, a prayer, a poem—‘They shall grow not old’—a minute’s silence and The Last Post

There are church services, radio and television broadcasts, concerts, gatherings and wakes throughout the day to remember sacrifice—the war dead and wounded, refugees and fugitives, and the whole sad sorry waste of it all. It is a statutory public holiday, restaurants, shops, schools and theatres are closed, normal life is on hold for a day, then it’s back to busy business. But ‘normal life’ has been on hold these many weeks now. So how was this Anzac Day different from other years?

Some today stood alone at the roadside in front of their home, before dawn at 6am, holding a candle perhaps, and a transistor radio to hear the national broadcast, or watched television coverage of the Prime Minister standing at her gate. Many families had made sculptures or graphics of poppies to display in their gardens. Some of the 1000s of teddy bears in house windows to cheer passersby these past weeks were today wearing poppies too. Many of us will have been mindful of the shocking statistic that in two months of the 1918 influenza pandemic more New Zealanders died than had been killed during the whole of World War I.

We’ve grown so accustomed to the commercialisation of Christmas and to a degree Easter, surrounded as we are by tsunamis of merchandise ‘to show we care’. Today was differently focused. Some folk had developed their own ideas and found resources to express an experience, share a thought, address a concern, tell a story, to give a voice to hope. Isn’t that what art does? Mere entertainment has to me never seemed sufficient, either in peace or wartime.

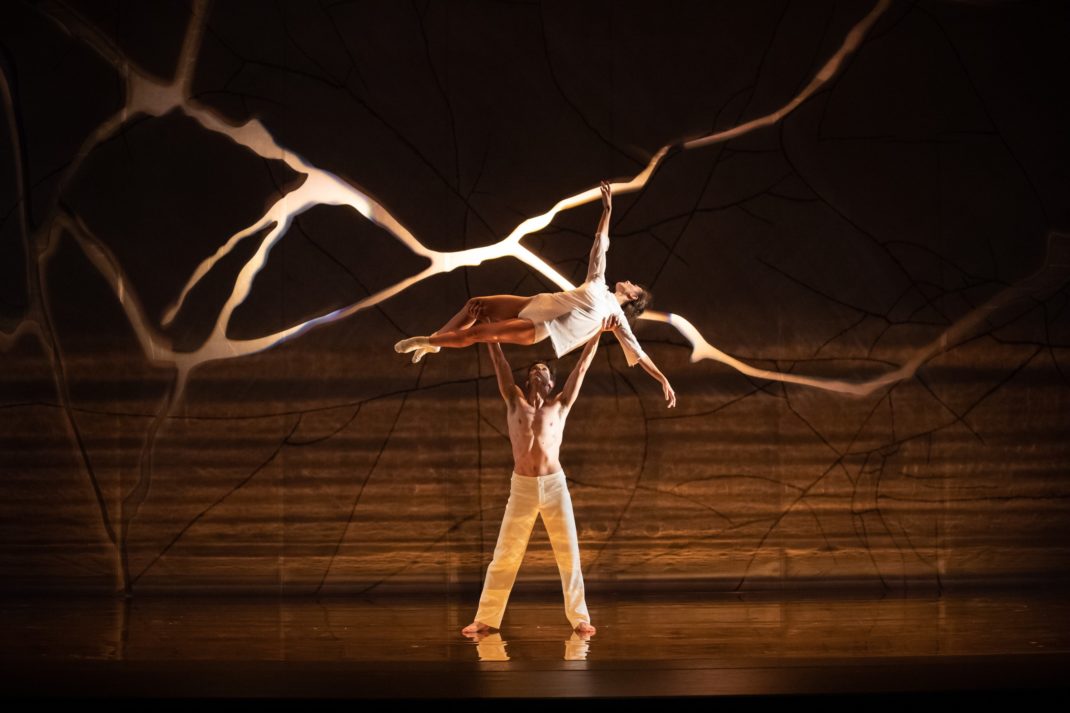

Numerous dance companies worldwide, stymied by the current pandemic and obliged to cancel many performances and productions, have in past weeks moved to make selected works from their repertoire available online. The Royal New Zealand Ballet have already screened video of Loughlan Prior’s Hansel & Gretel, Liam Scarlett’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Christopher Hampson’s Cinderella. For today their program from 2015, Salute, was aired, comprising two works—Andrew Simmons’ Dear Horizon and Neil Ieremia’s Passchendaele. My review of the Company’s season in 2015 is at this link.

What a pity this broadcast could not have included Jiri Kylian’s masterwork, Soldatenmis/Soldiers’ Mass, to Martinu, from the same program—(prohibitive fees or copyright issues perhaps?) since it was a work that suited the Company’s dancers of that time to the drumbeat of their hearts and ours. Laura Saxon Jones, sole female performing alongside all the male dancers of the Company, will never be forgotten.

Other outstanding choreographies with a war, or anti-war theme, include Jose Limon’s noble Missa Brevis, dedicated to the spirit of Polish resistance; Young Men, Ivan Perez’ choreography startlingly performed by Ballet Boyz; and of course the legendary work Der grüne Tisch/The Green Table, by Kurt Jooss, a work I used to dream might one day be performed by RNZB, so well it would have suited them until just a few years ago. I remain grateful to have seen the Joffrey Ballet’s authoritative performances however, and another unforgettable production in which the late Pina Bausch played The Old Woman—a performance of such chiselled beauty stays with one for life, as though she had stepped from a painting by Modigliani, or Munch, or a figure from the mediaeval Danse Macabre of Lübeck Cathedral.

(I’m often reminded of the very fine study by William McNeill, Harvard historian, who in his book Keeping Together in Time, considers how coordinated rhythmic movement, and the shared feelings it evokes, has been a powerful force in holding human groups together—how armies of the world, train and march and move—be that in quick, slow, double or dead march, the goose step, the North Koreans’ grand battement smash, or the soldiers’ antics at the Pakistan-Indian border).

***********************

Both RNZB works, Simmons’ Dear Horizon and Ieremia’s Passchendaele, retain all the impact and power of their first staging, with the New Zealand Army Band playing to precise perfection, for the former the music of Gareth Farr, for the latter the composition by Dwayne Bloomfield. The contained emotion of the music, particularly in cello and brass solos, stops time.

Ieremia’s early career, as for so many of the dancers who worked with Douglas Wright, absorbed much influence from the driven and airborne choreography of that master dance-maker. An indelible image that remains with me is from Wright’s The Kiss Inside—a scene in which a gorilla-suited figure passes a tray of cut oranges around a group of boys (a team of rugby players, refreshments at half time?). Soon, just a little older, the same young men are in a faraway other place, a different game, writhing on the ground, in an agony of wounds, bleating like sheep. The gorilla passes a microphone among them to record their messages for relaying home. The bleating becomes recognisable as a cry of pathos, ‘Mummy, Mummy’ from one dying soldier after another. Says it all really.

Jennifer Shennan, 25 April 2020

Featured image: Dancers of Royal New Zealand Ballet in Passchendaele, 2015. Photo: © Evan Li