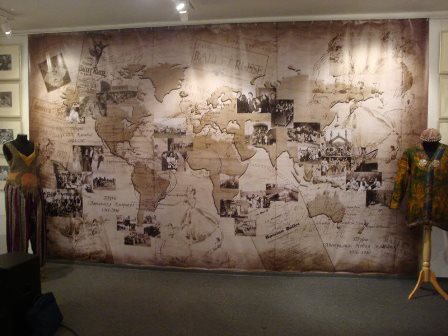

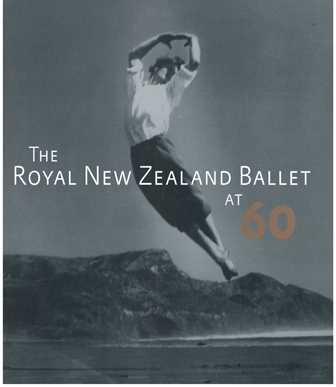

This handsomely produced book celebrates sixty years of performances by the Royal New Zealand Ballet. I say handsomely produced because its square-ish format is aesthetically pleasing and easy to hold in one’s hand, its illustrations are well reproduced and there are plenty of them both in black and white and colour, its paper is smooth and glossy and lovely to touch, and the layout of text and image leaves plenty of white space on the page so nothing looks jammed up.

Edited by Jennifer Shennan and Anne Rowse and published by Victoria University Press, The Royal New Zealand Ballet at 60 brings together a collection of articles, letters, reminiscences and poems covering the company’s fortunes from 1953 when it was set up by Danish dancer Poul Gnatt to its present manifestation under the direction of American artist Ethan Stiefel.

The first section consists of contributions from each of the company’s artistic directors, where they are still living. Poul Gnatt and Bryan Ashbridge, who are no longer alive, are represented with writing from Jennifer Shennan and Dorothea Ashbridge respectively. Then follows a collection of reminiscences and thoughts from a whole variety of people who work or have worked with the company—dancers, choreographers, board members, wardrobe staff and others closely connected with the company’s activities.

With this kind of arrangement of material, where there are at least fifty different contributors, some writing is bound to stand out and some is bound to be less interesting, less well written. The unevenness in the quality of the writing is perhaps the book’s shortcoming. But this is tempered by some vibrant writing and some fascinating stories that bring to life both the highs and lows of the company’s chequered history.

What struck me as I was reading the section on artistic directors was how much is revealed of a person’s approach to life and work through his or her writing. Harry Haythorne’s essay, for example, reveals the depth of thought that went into, and that continues to inform his work. Haythorne directed the company from 1981−1992. From this perspective I also enjoyed the essay by Gary Harris, artistic director from 2001−2010. It reminded me of the times I interviewed him and the friendliness of the man that I encountered on those occasions. I also enjoyed Shennan’s essay about founding director Poul Gnatt, filled as it is with information about Gnatt’s early life in Denmark.

From the reminiscences, I loved reading about Eric Languet, dancer with the company from 1988−1998 and for a few years resident choreographer, in his essay ‘I would like to come home one day’. Although he has some Australian connections, his and my paths have never crossed. He writes with admirable honesty about his time in New Zealand and one of my favourite images in the book is from Alice, which he choreographed in 1997. And reading Douglas Wright’s account of performing the leading role in Petrouchka is, quite simply, a rare privilege. It is unusual to hear in some depth from artists about their approach to a role and their thoughts as they prepare for and then perform it. Wright’s essay is followed by a poem, ‘Herd’ written by Wright and beginning with the delicious line ‘a herd of cows does not need a choreographer’. Readers may be surprised at how the poem ends too!

One typo in the book makes me wince somewhat. In Una Kai’s essay (Kai was director from 1973−1975), which is interesting for a whole variety of reasons, Lew Christensen’s name is wrongly spelt. Typos are the bane of all our lives but it is not the best when personal names don’t get the attention they deserve.

Unlike other recent publications in a similar vein, and despite any shortcomings I might find in it, The Royal New Zealand Ballet at 60 makes a useful contribution to the history of the Royal New Zealand Ballet. Its editors, contributors and publisher deserve to be congratulated for avoiding making it into some kind of media driven, ultimately barren publication.

Jennifer Shennan and Anne Rowse (eds), The Royal New Zealand Ballet at 60, (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2013) Hardback, 350 pp., illustrated

ISBN 978086473891

RRP NZD 60.00

Michelle Potter, 29 August 2013