- Australian Dance Awards 2013: Lifetime Achievement and Hall of Fame

The 2013 Australian Dance Awards will be presented in Canberra on 5 August. In advance of that date, recipients of the two major awards, Lifetime Achievement and Hall of Fame, have been announced. Ronne Arnold is the recipient of Lifetime Achievement and he is seen above with members of his company, the Contemporary Dance Company of Australia, in a finale to one of their shows.

I was a student with Joan and Monica Halliday when Ronne began to teach there in the 1960s and, while I was far from a jazz dancer, I took Ronne’s classes and also followed him one year to an Arts Council Summer School. He was (and no doubt still is) a wonderful teacher and I continue to treasure memories of those classes. My brief story about him for The Canberra Times is at this link. [Update 28 April 2019: link now no longer available]

An oral history interview with Ronne Arnold, recorded in 1997 and 1998, is held by the National Library of Australia. Cataloguing details are at this link. (Note of caution: the transcript, although classed as ‘corrected’ in the catalogue, still needs a number of corrections here and there!)

The recipient of the Hall of Fame award is Alan Brissenden whose book Australia Dances. Creating Australian Dance 1945–1965 (co-authored with Keith Glennon), has been invaluable to me in many ways since it was published in 2010 by Wakefield Press. He too will receive his award on 5 August.

- Heath Ledger Project

In mid-July I was lucky enough to record the first of the interviews with NAISDA graduates for the Heath Ledger Young Artists Oral History Project. Beau Dean Riley Smith graduated from NAISDA in 2012 and is now dancing with Bangarra Dance Theatre. He gave a wonderfully frank interview, punctuated with much laughter, and it was a thrill to see him perform in Blak the next night at the opening of Bangarra’s Canberra season. I was impressed with the way he immersed himself totally in the production and admired his exceptional physicality.

The interview was conducted in a studio at the National Film and Sound Archive in Canberra surrounded by all kinds of sound equipment being used for restoration projects (which does not make an appearance in the recording!), as you can see in the image above. Another NAISDA graduate, independent artist Thomas E S Kelly, is to be interviewed for the project during August.

And as an update to the project in general it was a thrill to hear that Hannah O’Neill, who was interviewed for the project in May 2012, was placed first in the Paris Opera Ballet examinations this year and has been offered a permanent (that is lifetime) contract with the Paris Opera Ballet. A singular achievement and one that demonstrates not only O’Neill’s exceptional talents but her absolute determination to make it in the company she regards as the best ballet company in the world.

In addition, the other Australian Ballet School graduate interviewed for the project in 2012, Joseph Chapman [now going by the name Joe Chapman], tells me that, although his first eighteen months with the company have been ‘challenging’, performing has been a real highlight for him.

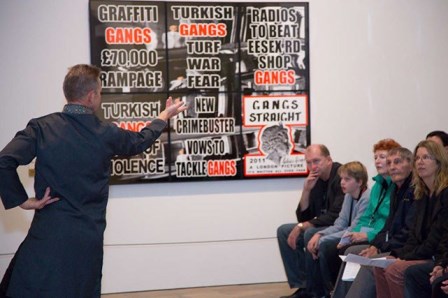

- Cecchetti Society Conference 2013, Melbourne

At the beginning of July I had the pleasure of chairing a session at the 2013 Cecchetti Society Conference in Melbourne. The session concerned the National Theatre Ballet, a company that gave its first performance as a fully-fledged company under the directorship of Joyce Graeme in 1949.

In the photo above I am standing behind the eight participants on the panel, all former dancers from the National Theatre Ballet: (seated left to right, Lorraine Blackbourne, Jennifer Stielow, Dame Margaret Scott, Athol Willoughby, Norma Hancock (Lowden). Phyllis Jeffrey (Miller) Maureen Trickett (Davies) and Ray Trickett. Each of the participants had wonderful stories to tell of their time with the company and the session could have gone on for many hours.

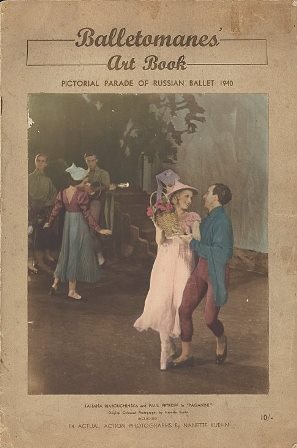

There is still much to be written about the impact of Ballet Rambert in Australia. Here, however, is an article, an overview of the Australian tour, which I wrote for National Library of Australia News in December 2002.

- Press for July

‘Tragedy without end’. Review of Big hART’s Hipbone sticking out. The Canberra Times, 5 July 2013. [Online link now no longer available]

‘New direction respects company’s past’. Review of Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Blak. The Canberra Times, 13 July 2013. [Online link now no longer available]

‘Moving body of work’. Article on Ronne Arnold as the recipient of the 2013 ADA Lifetime Achievement Award. The Canberra Times, 30 July 2013.[Online link now no longer available]

In July The Canberra Times also published an article I wrote on Paul Knobloch although for reasons of copyright I am not providing a link.

Michelle Potter, 31 July 2013