16 April 2025 (matinee), Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

John Neumeier’s Nijinsky is a spectacular and highly complex work. I have had the good fortune of seeing it several times (twice by Hamburg Ballet, the company for which the work was made in 2000). In terms of the nature of the work and its relationship to the dramatic life of Vaslav Nijinsky, I can’t do any better than provide a link to the time Hamburg Ballet presented it in Brisbane in 2012 (now unbelievably over 10 years ago). Here is the link to that review.

Nevertheless, each time I see Neumeier’s Nijinsky I notice something a little more clearly than I did on previous viewings. It’s that kind of work. It opens up further with each viewing. I was staggered this time by Neumeier’s choreography as it was so clear that his choice of movement was just brilliant in the sense that it captured the intrinsic nature of the characters represented. Perhaps my awareness of the power of Neumeier’s choreography was heightened as a result of seeing (and disliking) Schachmatt (Checkmate in English translation) from Spanish/international choreographer Cayetano Soto with its dismantling of the balletic vocabulary. Neumeier also dismantled the vocabulary to a certain extent but those splayed fingers, flat palms of the hand, bent elbows, twisted bodies and the like were so much part of the erratic and obsessive behaviour that marked the last years of Nijinsky’s life. They had a meaning that was absolutely within the narrative. (Not so with Schachmatt.)

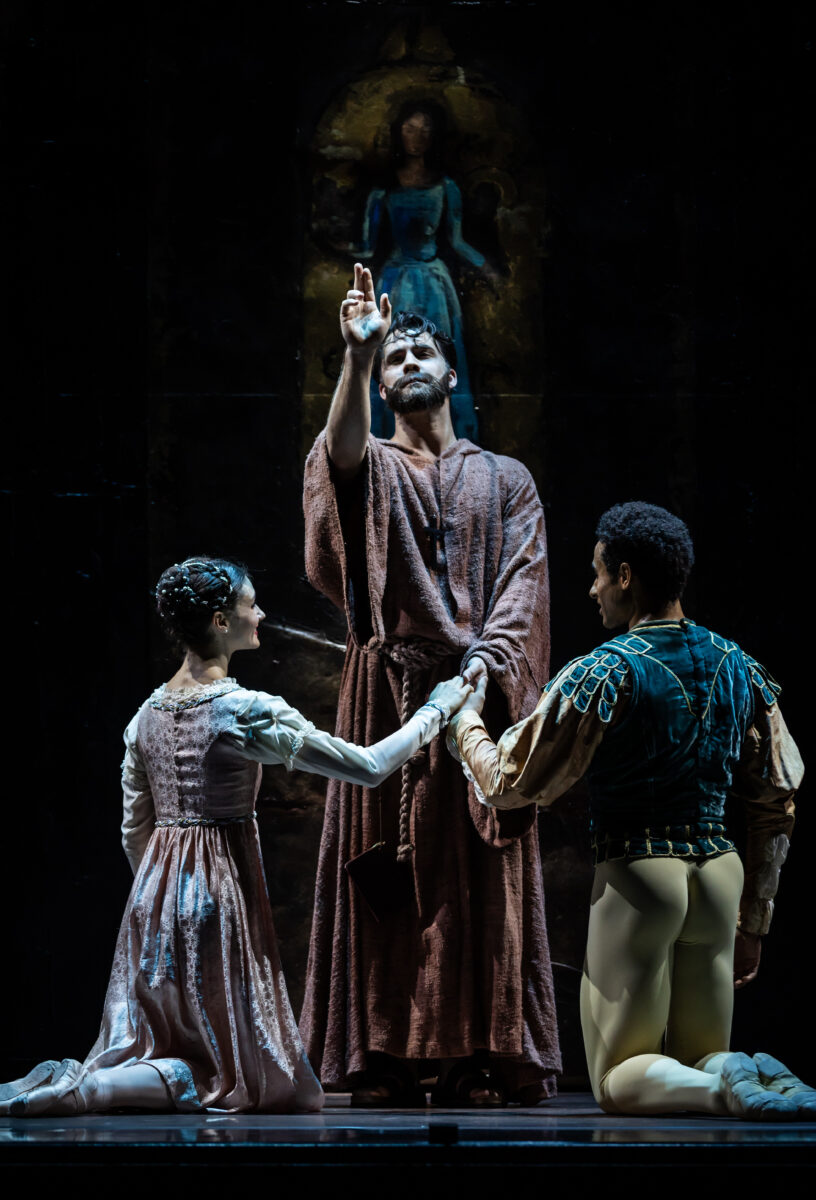

Of the cast I saw on this occasion, a mid-season matinee, I was impressed in particular with Mia Heathcote as Romola Nijinska, especially in her short scenes with the Doctor, danced by Jarryd Madden, who was treating Nijinsky for a range of issues. Nijinska’s infidelity was very clear. I also was impressed by Luke Marchant who danced the role of Nijinsky as Petrushka, especially in Act II when his dramatic solo was strongly presented.

In general the Australian Ballet dancers performed reasonably well with Elijah Trevitt in the lead role of Nijinsky. But I guess I longed for something that approached the absolute power of other occasions that I have been lucky enough to have seen.

Michelle Potter, 18 April 2025

Featured image: the opening scene (with Kylie Foster at the piano) of Nijinsky showing the ballroom of Suvretta House, St Moritz, where Nijinsky gave his last performance. Photo: © Michelle Potter