19 November 2015, Te Whaea, Wellington

Reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The New Zealand School of Dance (NZSD) graduation program opened with Paquita, staged by Anna-Marie Holmes, after Petipa’s vintage choreography from 1846, offering as many challenges today as it no doubt did back then. In another layer of heritage Nadine Tyson, the tutor who rehearsed the work, danced in it at her own NZSD graduation back in 1988. The luxuriant music by Minkus demands a festive commitment, and the students aspired to this with flair. Soloist Lola Howard in one of the variations caught our eye with her sense of line, and technical command.

Sarah Foster-Sproull, also a former NZSD graduate, created Forgotten Things, to music by Andrew Foster, in a premiere work for this season. A series of highly effective images, with light shining on skin of limbs in a kinetic sculptural effect, cohered the piece throughout. The mediaeval dance-like rhythms supported well the work’s theme of community undergoing change.

Cnoditions [not a typo] of Entry, an enigmatic and somewhat troubling work choreographed by Thomas Bradley, (no program profile so perhaps he prefers the anonymity?) had a line of robed and hooded figures in very low light levels that suggested sinister or secret machinations of covert behaviour among the members of a small and closed group. The program notes also appear to be in code (and a pity that the printed program is overall an uneven affair).

Tarantella, Balanchine’s quirky number from 1964, to Gottschalk’s jaunty music, was danced with effervescent style and vivacity by Mayuri Hashimoto and Felipe Domingos (the latter a promising young dancer from Brazil who has been confirmed in a contract to join Royal New Zealand Ballet). Diana White staged the piece which was rehearsed by Qi Huan, until recently a fine lead dancer with RNZB. His artistic conviction shone through the students’ performance (though Poul Gnatt would have required their somewhat quiet tambourines to be shredded by the end of the performance).

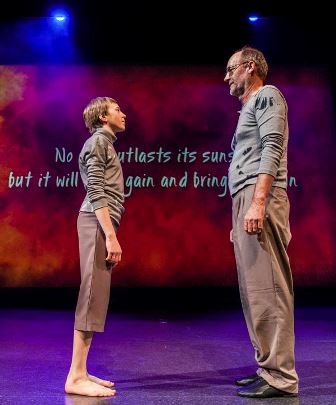

As It Fades, choreographed by Kuik Swee Boon of Singapore, to an atmospheric score, was performed here in excerpts, so it’s hard to gauge the work’s context. There was noticeable contrast within its structure—speed and flight, moving through to a calm and quietly iexplored place, performed with strong focus—as if above ground, but then under water.

The final and major work on the program was Concerto, choreographed by Kenneth MacMillan, premiered in Berlin in 1966. The rapport between MacMillan and dancer Lynn Seymour, whose distinctive qualities as a richly poetic and dramatic dancer inspired the making of the main duet, survives to again inspire the very fine and fresh performance it received here from Lola Howard and Jerry Wan Jiajing. Lynn Wallis staged the work, with Stephen Beagley and Turid Revfeim also involved. The Shostakovich piano concerto #2 was beautifully performed by Ludwig Treviranus and Craig O’Malley on two pianos sidestage. The colour gradations of costumes made attractive foil to each other and were the most successful of the evening.

Ballet is nothing if not faithful to its repertoire, but new choreographies in that idiom are very rarely commissioned or forthcoming—yet its movement vocabulary is able to speak to us of our lives and loves and concerns—witness that serene and timeless Concerto pas de deux. Contemporary dance, by contrast, is rarely studied or staged here through the classics of its own heritage repertoire and too often it has only a single season life. These are not parallel streams in choreography since they are one and the same art. Only through studying and seeing both repertoires do we know and understand that, and ourselves, as performers and as audiences. No doubt the School’s upcoming 50th anniversary will draw attention to the legacy of those decades.

This program offers challenges to the students, and opportunities to be savoured by the audience. The fact that your favourites will be different from mine is the rich treasure that the musical and non-verbal nature of dancing invites. It matters not whether old or new, borrowed or blue, ballet or contemporary dance. What matters is that it be good, and that choreographers and dancers know what to do with their music. All encouragement to the students as they make their way into careers in dance.

Jennifer Shennan, 24 November 2015