- Anna Karenina. The Australian Ballet

During March I watched a streamed showing of Anna Karenina from the Australian Ballet. Choreographed by Ukrainian-born choreographer (currently resident in the United States) Yuri Possokhov, this production of Anna Karenina premiered in 2021 in Adelaide with just a few performances, but its presentation in other States had to be cancelled, and cancelled, until March 2022 when it opened in Melbourne.

I was struck more than anything by the spectacular set design (Tom Pye), which for the most part was quite minimal but nevertheless evocative, and which frequently moved seamlessly to new features as locations changed. But I found the lighting (David Finn) quite dark for most of the production, with the major exception being the peasant-style ending, which I’m not sure was an essential part of the story to tell the truth. I’m not sure either if the consuming darkness was more a result of the streaming situation or part of the overall production. But the darkness was annoying.

There were some strong performances from Robyn Hendricks as Anna and Callum Linnane as Vronsky but perhaps the strongest characterisations came from Benedicte Bemet as Kitty and Brett Chynoweth as Levin. But I am not sure that this production is ideal for streaming and I am looking forward to seeing it live in Sydney in April.

But on the issue of the history of productions based on the Tolstoy novel Anna Karenina, I recently came across a ’Stage Direction’ article by Stephen A. Russell published on the website of the Sydney Opera House. It gave an interesting, short introduction to the variety of ways in which the novel has been used in a theatrical manner. The article is currently available at this link, although may not be there for the long term.

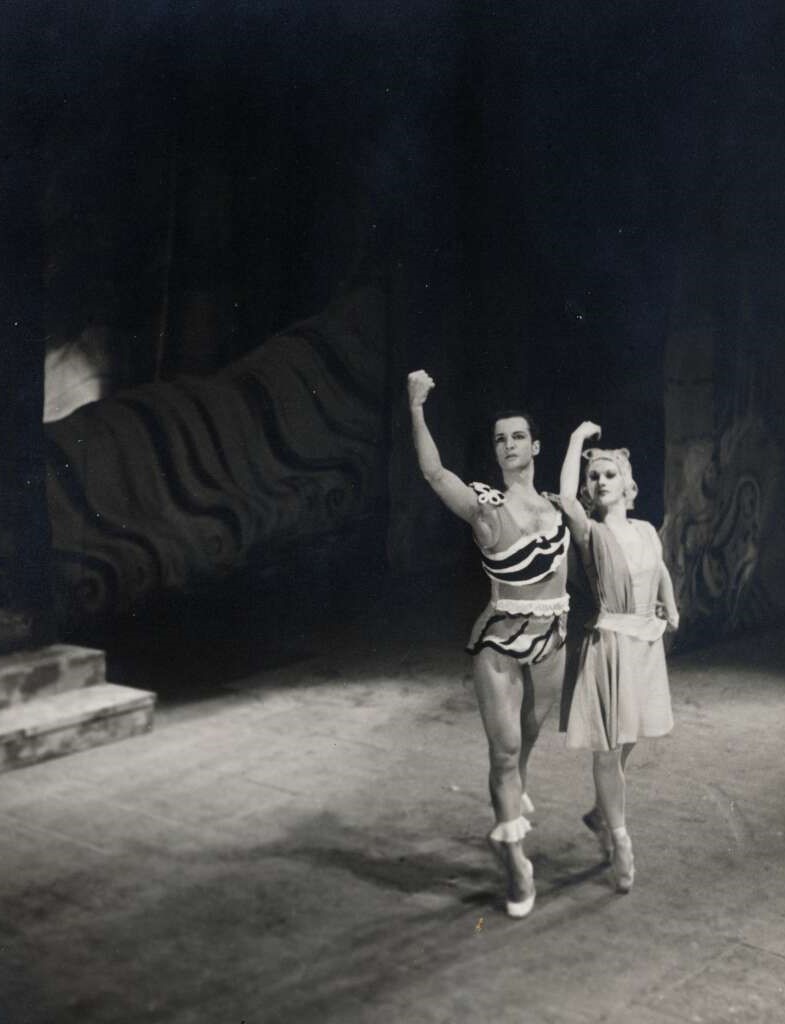

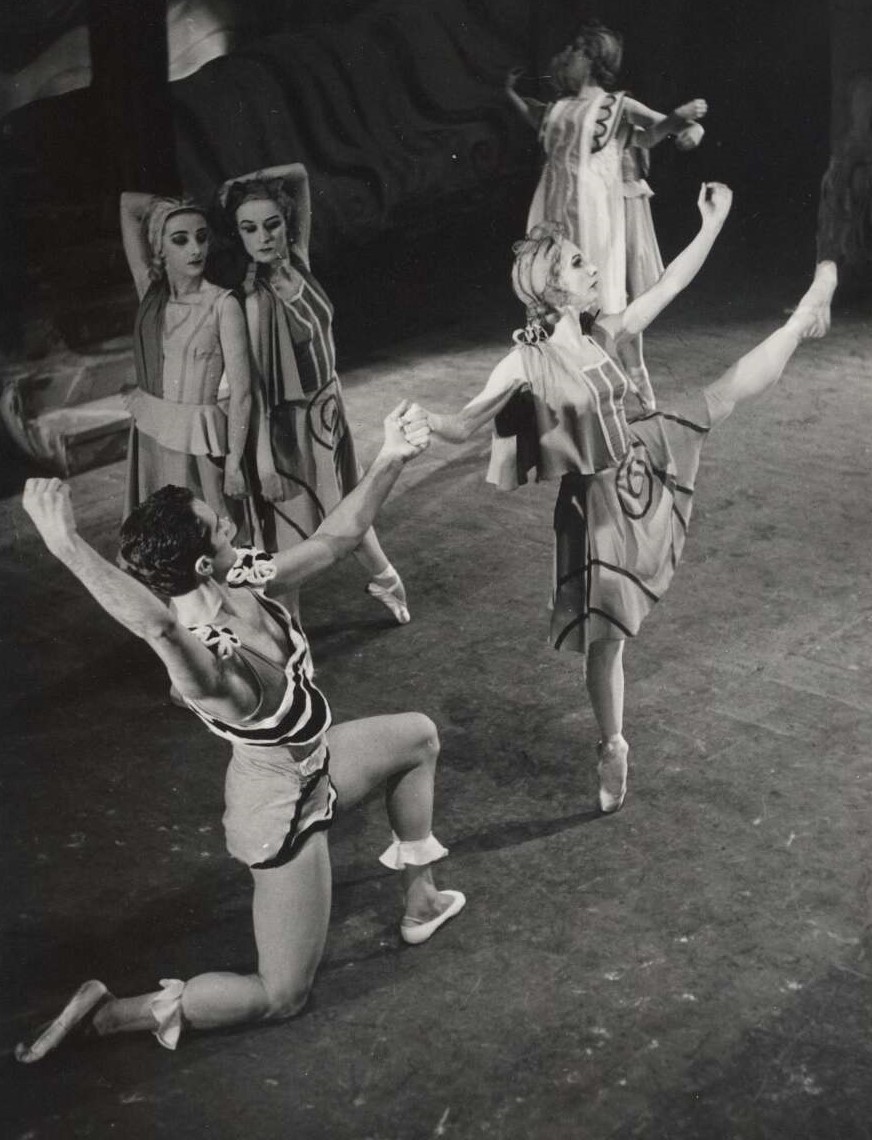

- Henry Danton (1919-2022)

The death of leading dance personality Henry Danton was announced back in February. Read the obituary by Jane Pritchard published in The Guardian at this link.

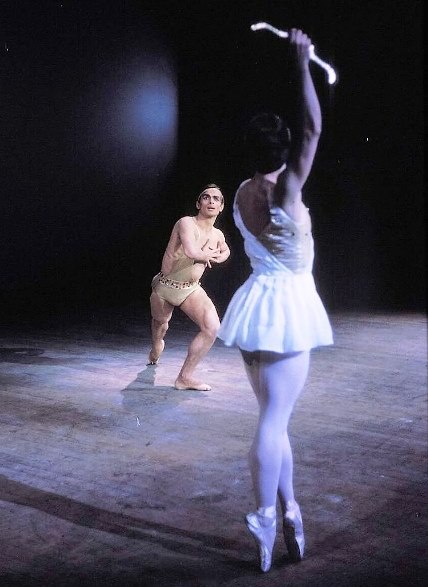

Henry Danton also played a significant role in the growth of professional ballet in Australia. He was a guest artist with the Melbourne-based National Theatre Ballet over several years and during that time consistently partnered Lynne Golding, including in the National’s full-length production of Swan Lake and in Protée, staged for the company by Ballets Russes dancer Kira Bousloff before she moved to Perth to establish West Australian Ballet.

- Bangarra Dance Theatre

Bangarra Dance Theatre recently announced the departure from the company of three dancers, wonderful artists who have given audiences so much pleasure in recent productions. Baden Hitchcock, Rika Hamaguchi and Bradley Smith have left the company to pursue other options. All three are beautiful dancers and I’m sure their future careers will continue to give us pleasure.

Other news from Bangarra is that the company’s children’s show Waru—journey of the small turtle, cancelled last year due to COVID, will be coming to the stage later this year. Conceived and created by Stephen Page and Hunter Page-Lochard, along with former Bangarra dancers and choreographers Sani Townson and Elma Kris, Waru tells the story of Migi the turtle who navigates her way back to the island where she was born. Waru is on in Sydney from 24 September to 9 October 2022 in the Studio Theatre at Bangarra’s premises at Walsh Bay.

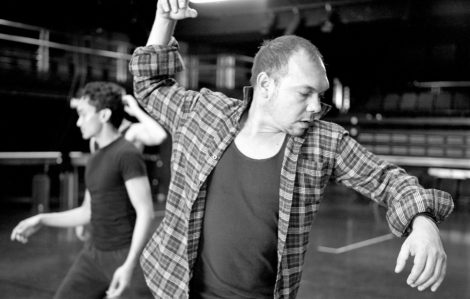

- Russell Kerr (1930-2022)

Prominent New Zealand dance personality Russell Kerr died in Christchurch earlier this month. Read an obituary with a great range of images at this link. I am expecting an obituary from his close friend and colleague Jennifer Shennan shortly and will publish it on this site when received. For further material on Russell Kerr and his activities on this website follow this tag.

Michelle Potter, 31 March 2022

Featured image: Robyn Hendricks as Anna and Callum Linnane as Vronsky in Anna Karenina. The Australian Ballet, 2022. Photo: © Jeff Busby