2 February 2024. Opera House, Wellington

by Jennifer Shennan

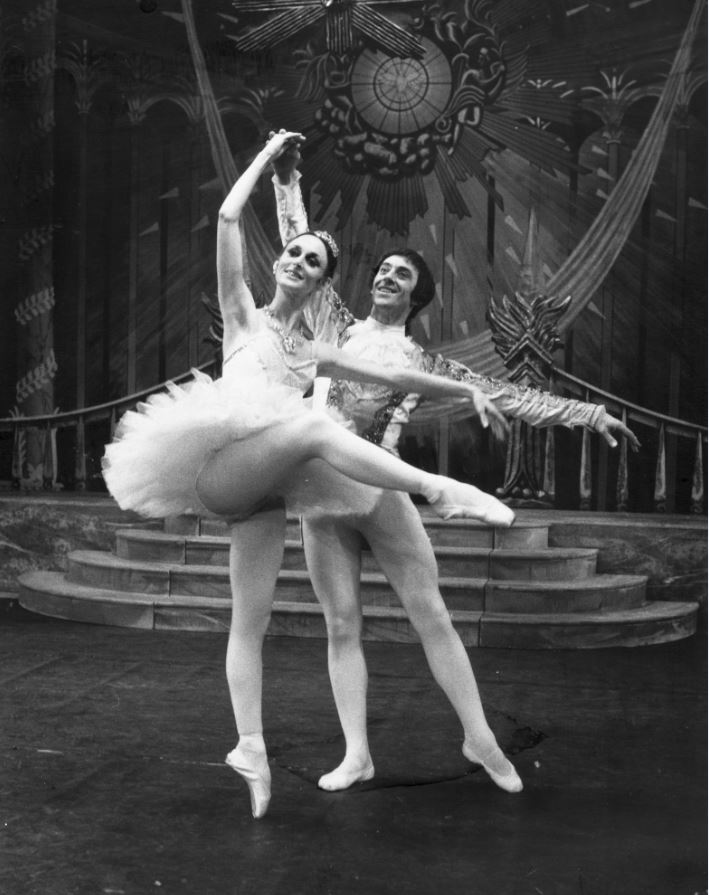

Sir Jon Trimmer, dancer extraordinaire and leading artist of the Royal New Zealand Ballet for decades, died in October 2023. Yesterday a Tribute to the man and artist was presented in Wellington to a capacity audience at the Opera House. Guest of Honour was Jacqui, Lady Trimmer, also a dancer with RNZB, who was at Jon’s side throughout his 60 year performance career

The event was designed and prepared by Turid Revfeim, former dancer with Company, and more recently artistic director of her independent Ballet Collective Aotearoa.

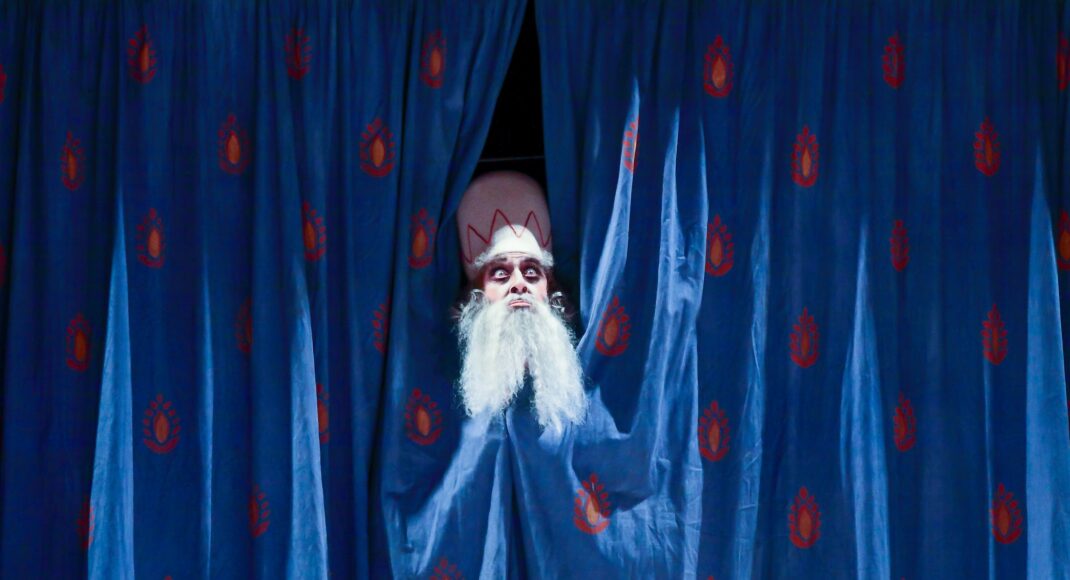

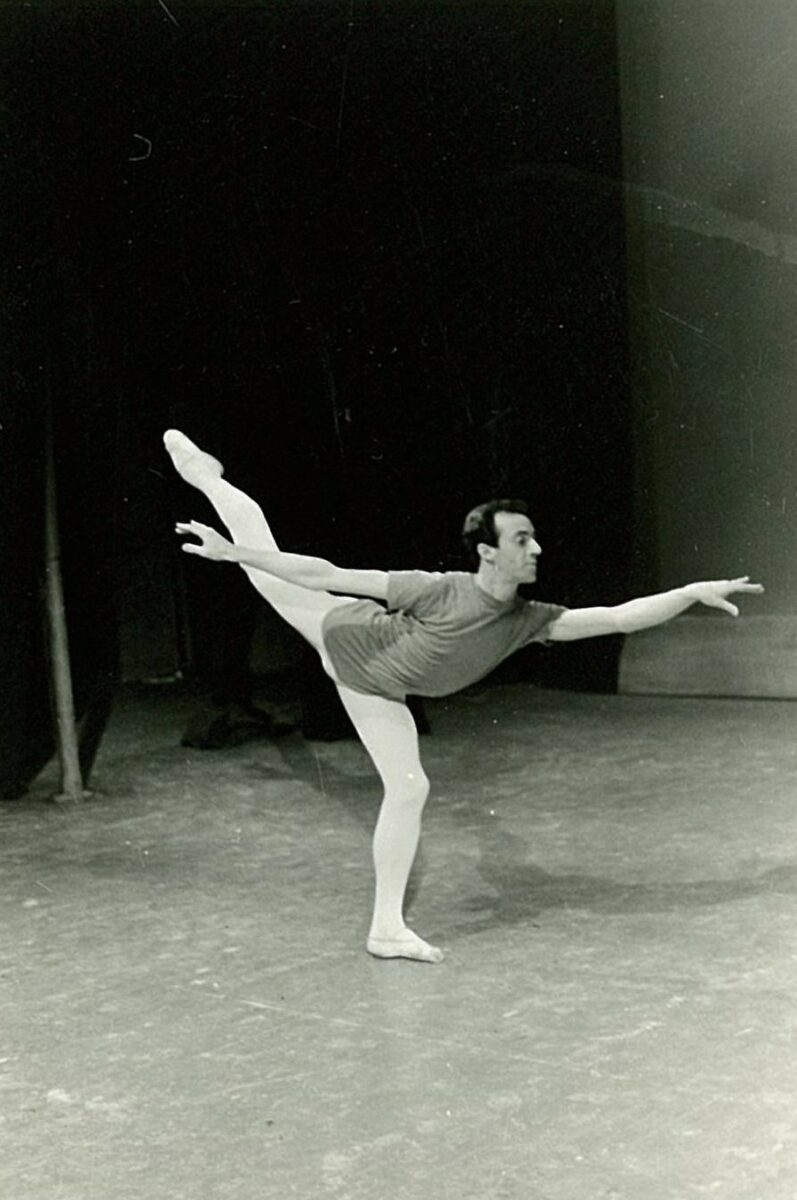

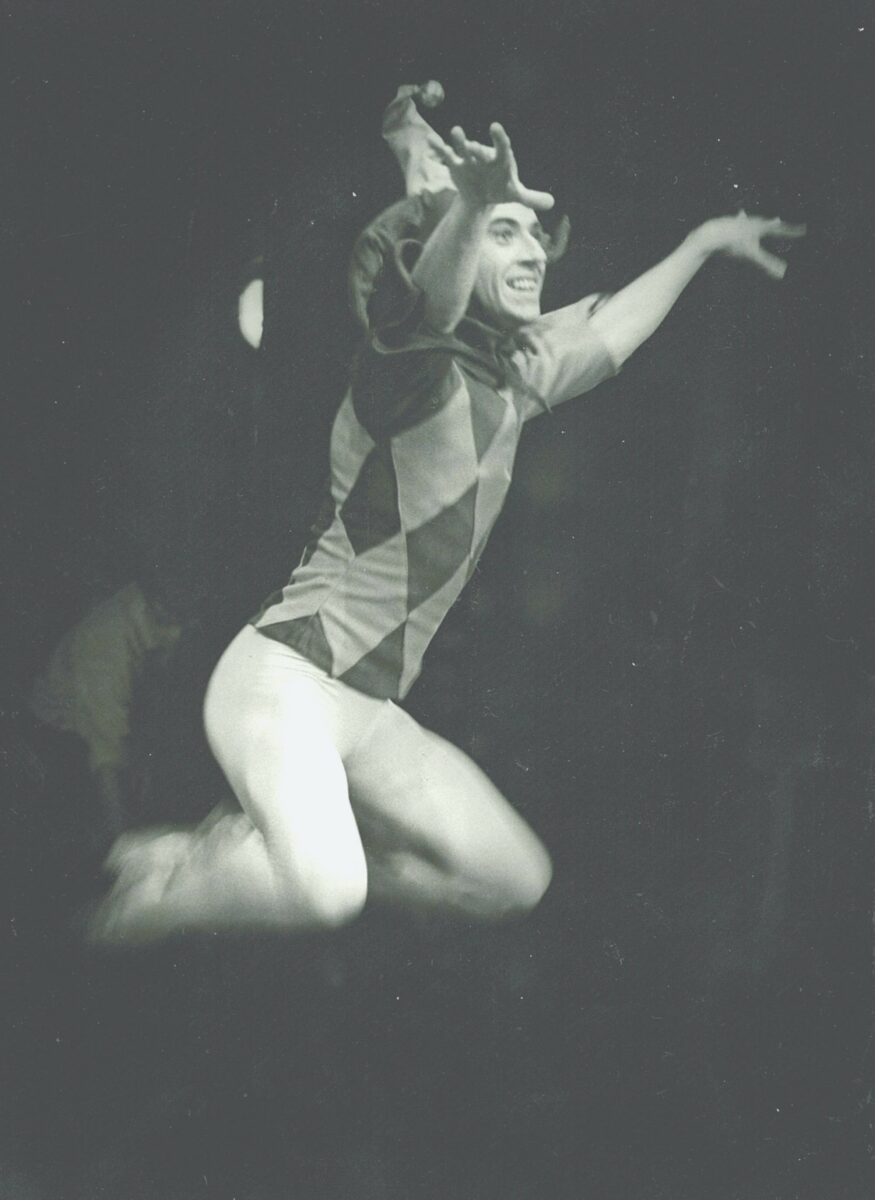

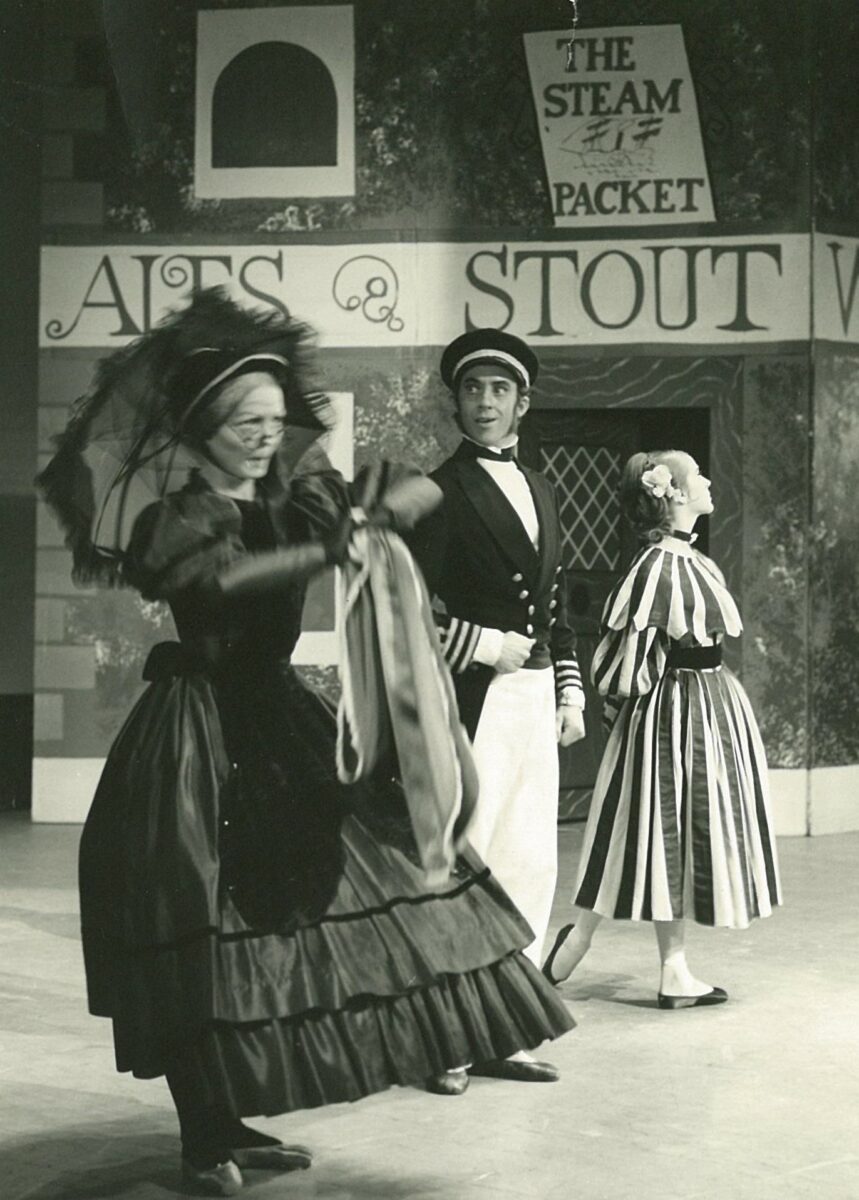

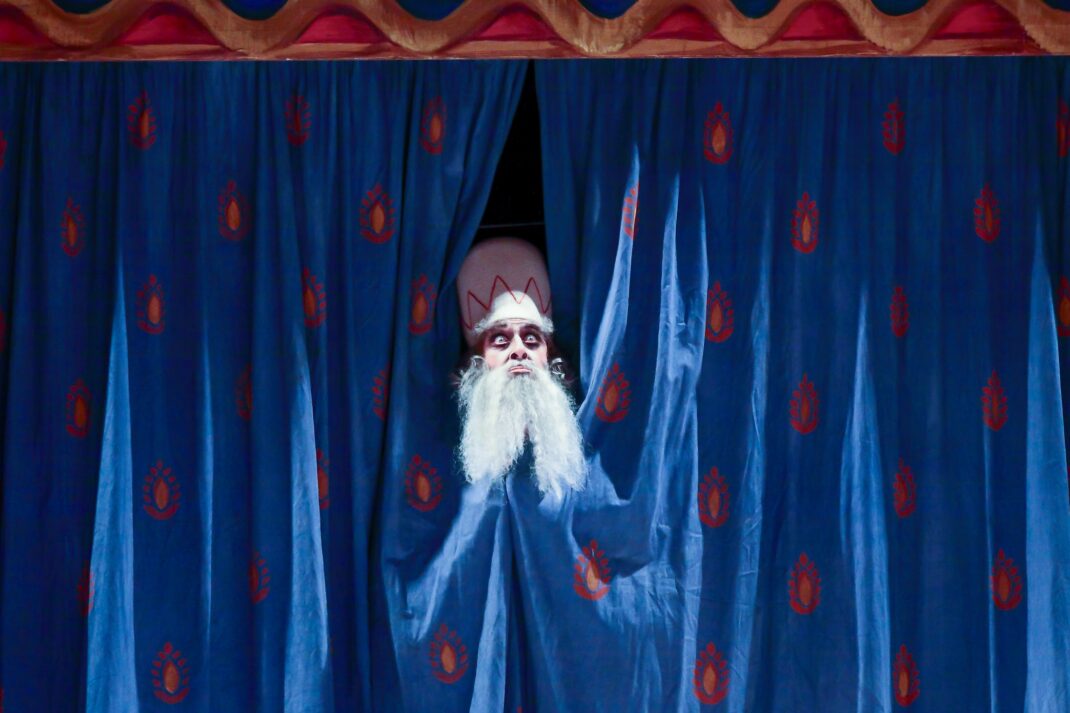

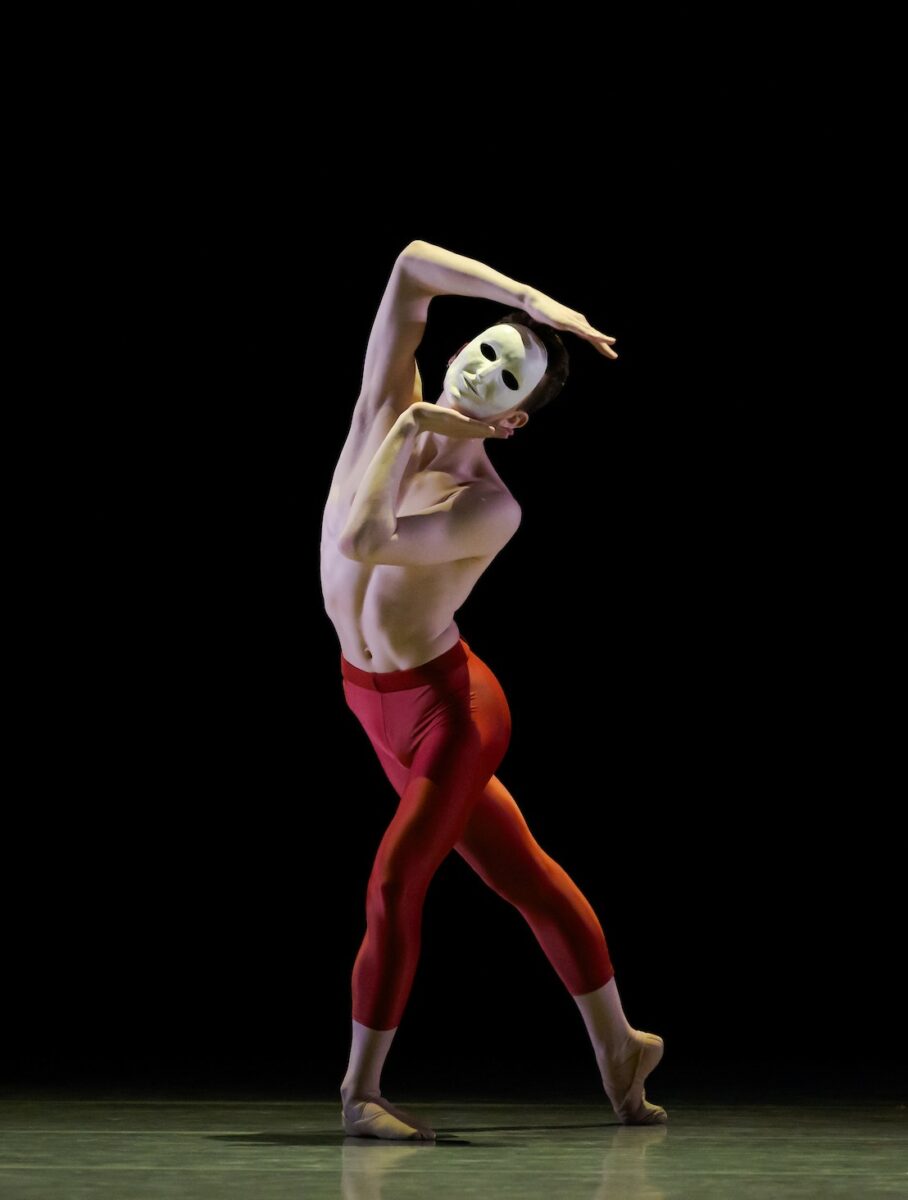

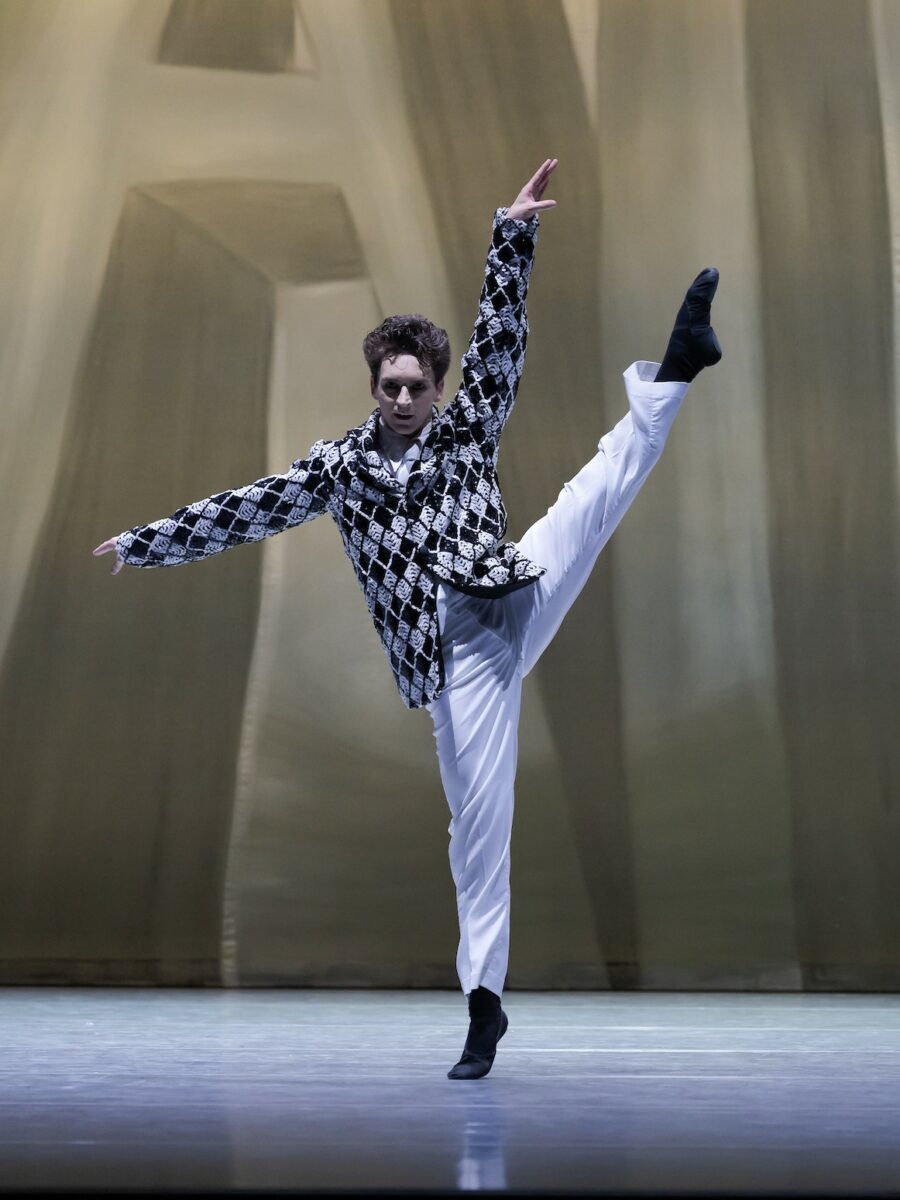

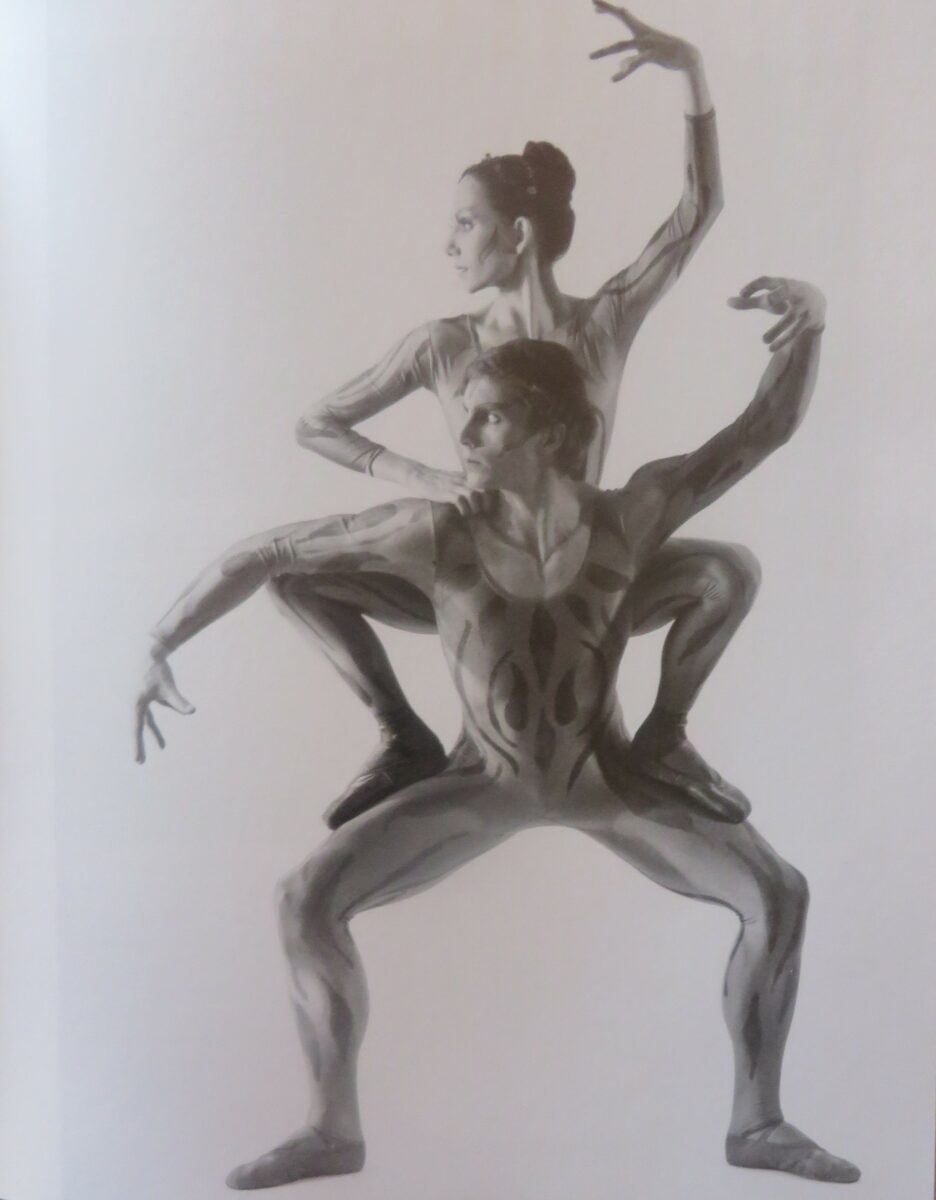

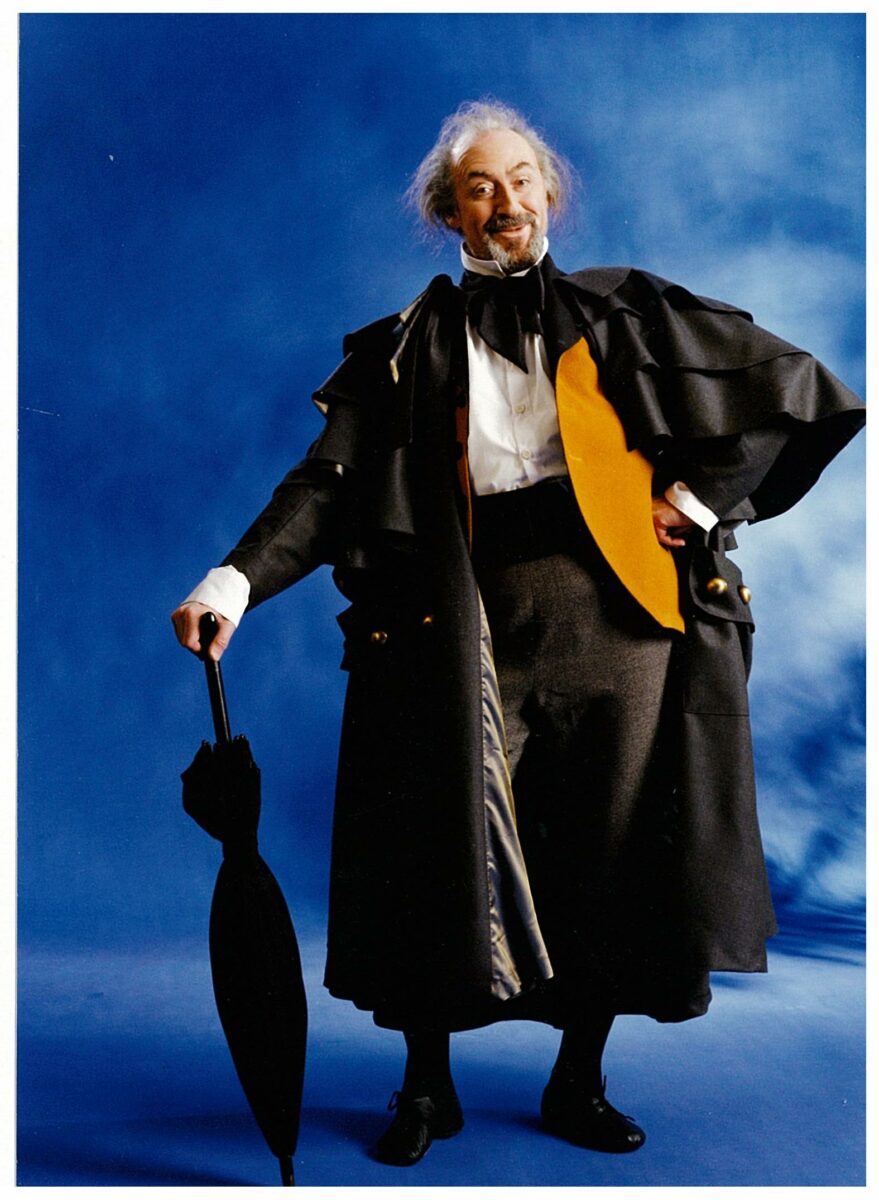

We were reminded of the extraordinary range of Jonty’s roles in spoken tributes, photo images, film excerpts of him dancing, and live performances by current members of RNZB. Jon had danced in all the classics—(his favourite was Albrecht, and we also saw film of him as the visionary poet in Les Sylphides). In dramatic roles there were so many favourites but let’s mention Friar Lawrence and Duke of Verona in Christopher Hampson’s Romeo and Juliet; the debauched King in André Prokovsky’s Königsmark; Dr Coppélius in Russell Kerr’s Coppélia; the stunning Swan in Bernard Hourseau’s Carmina Burana; a compelling toa/warrior in Gaylene Sciascia’s Moko; the enigmatic Man in Ashley Killar’s No Exit; and the poignant Leopold in Gray Veredon’s Wolfgang Amadeus—in a duet-minuet with the inimitable Eric Languet. In comedy roles Jon relished Stepmother in Cinderella, Pantalone in Veredon’s The Servant of Two Masters, The Matron in Gary Harris’ The Nutcracker, and goofing through the title role in Harris’ Don Quixote.

All those memories are worth gold, but it’s apparent to anyone who thinks about it that Gray Veredon was/is New Zealand’s exceptional choreographer with a unique imagination, style and sensibility. Jon was 41 when he first danced the outrageously wonderful solo as The Entertainer in Veredon’s Ragtime Dance Company. No one on the planet ever did or could match that performing. At age 80 Veredon is still active on the international choreographic stage, with recent successes in Warsaw and Venice, and now in Mexico. How fine and fitting it would be for RNZB to re-stage some of his stellar works—perhaps Firebird and Tell Me A Tale for starters.

In 2006 Peter Coates directed and produced a wonderful documentary of Jon’s career from which excerpts were screened. How wonderful to see and hear Russell Kerr in such good voice analysing Jon’s talents. The film will be a valuable resource for years to come.

Tributes were received from former artistic directors of RNZB—Harry Haythorne (by proxy from Mark Keyworth), Ashley Killar, Patricia Rianne, Gary Harris, Matz Skoog, Ethan Stiefel and Francesco Ventriglia—and were read by Anne Rowse, former director of New Zealand School of Dance.

Breathing stopped when Helen Moulder started a cameo from her poignant play, Meeting Karpovsky, that she and Jon performed many times. How could she do that with half the cast missing? But suddenly there was Kim Broad who quietly appeared from the shadows in a miraculous summoning of Jon’s presence. That was the true moment of theatre in the whole event.

The next Russell Kerr Lecture in Ballet & Related Arts, the sixth in the annual series, to be held in Wellington on Sunday 25 February 2024, will be all about Jon Trimmer. Turid Revfeim is the main presenter, with a number of other contributors, and we will also screen the complete Coates’ documentary. For those readers able and interested to attend, please email jennifershennan@xtra.co.nz for an invitation.

We are already thinking ahead that 2025’s lecture will be on Gray Veredon. Perhaps the year after that might be Eric Languet?

Jennifer Shennan, 3 February 2024

Featured image: Jon Trimmer in Helen Moulder’s Meeting Karpovsky. Photo: © Stephen A’Court