30 June 2017, Lyric Theatre, Queensland Performing Arts Centre, Brisbane

What a pleasure it was to see Wayne McGregor’s Woolf Works again, and to have one’s first impression strengthened. Woolf Works remains for me one of those exceptional works that reveals new insights with every new viewing. In Brisbane, as part of the program by the Royal Ballet on its visit to Australia, it was performed with all the panache and brilliance I have come to expect from this absolutely world class company.

Casting for the Brisbane opening was, with the major exception of Sarah Lamb who did not appear due to injury, largely the same as that which British audiences would know as ‘first cast’ with Alessandra Ferri in the lead as Clarissa Dalloway. Looking back at my review from earlier this year, at this link, I stand by what I wrote then. But below are some aspects of the work that I loved this time, which I didn’t notice to the same extent earlier.

Act I: ‘I now/I then’ (based on Mrs Dalloway)

- Sitting much closer to the action on this occasion, I admired the complexity of Wayne McGregor’s choreography. There were fascinating small movements of the hands and fingers, for example, and the dancers showed every tiny movement with great clarity and with a real sense of pleasure in performing them.

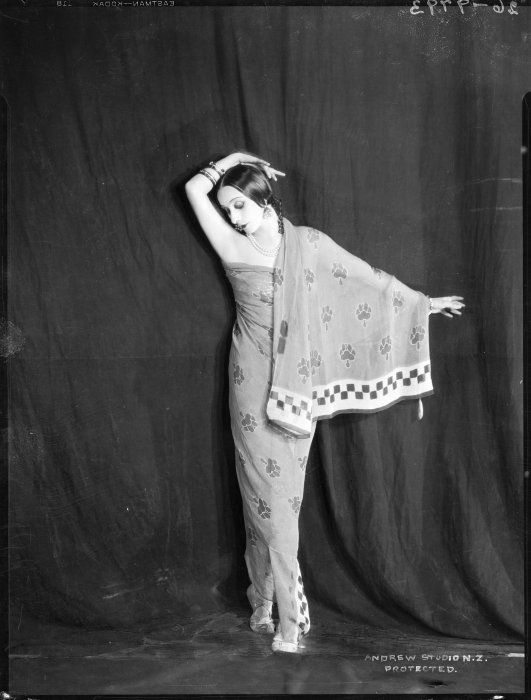

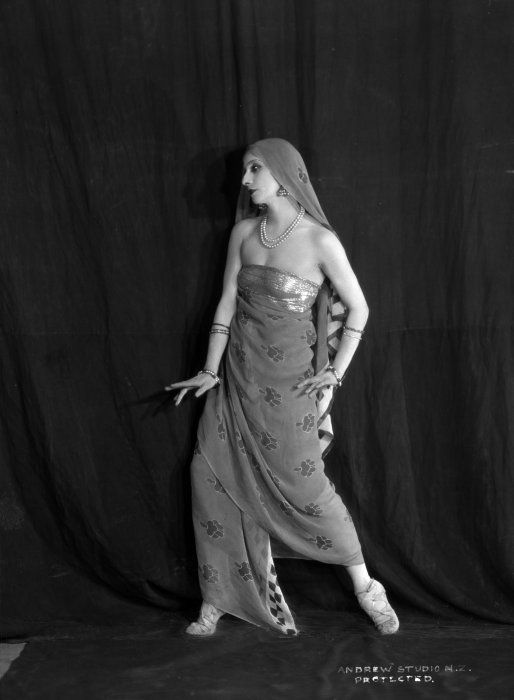

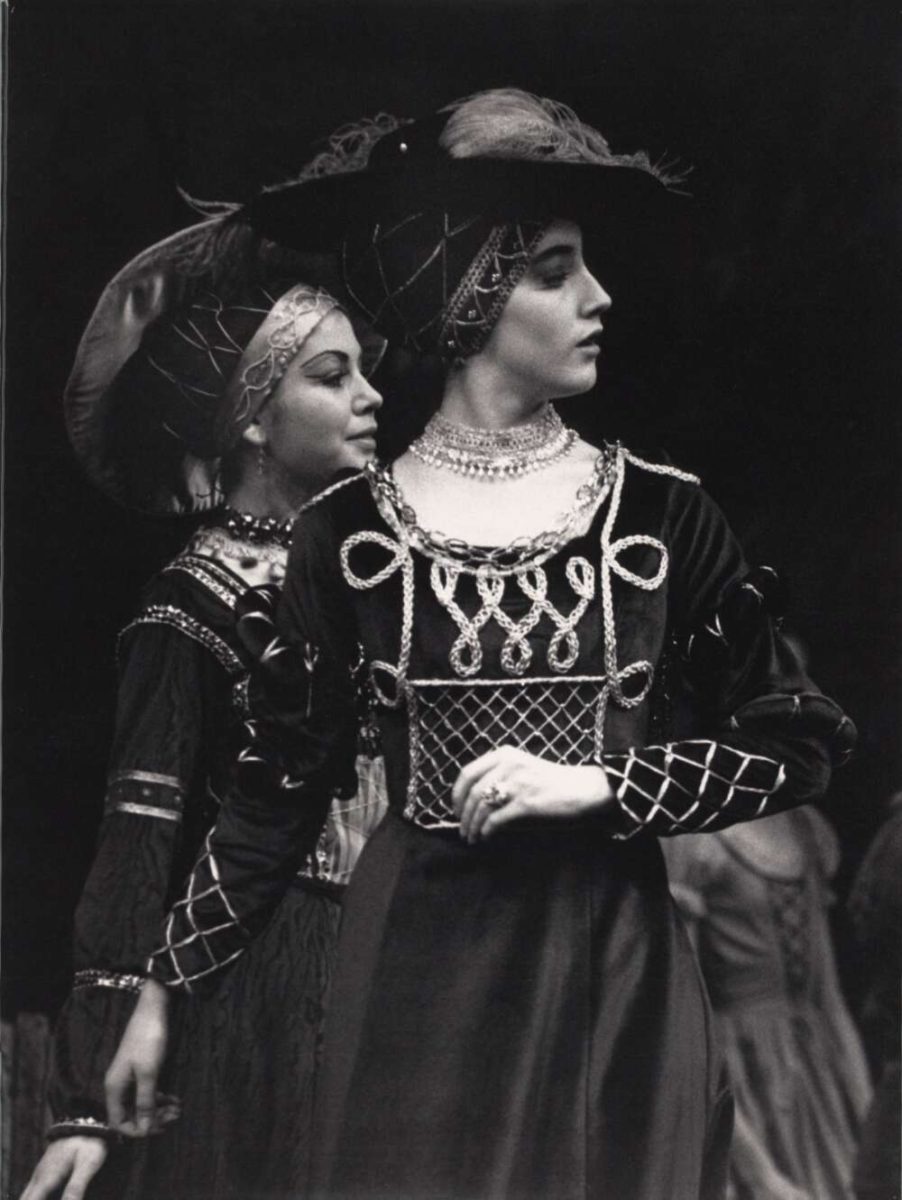

- Truly satisfying was the way in which the ending of this first act returned to, but reversed the sequence of and brought new understanding to the opening moments. As ‘I now/I then’ begins Clarissa Dalloway stands on stage, a solitary, reflective figure. She is then joined by the main characters we will see interacting with her throughout the act, in particular the young Clarissa (Beatriz Stix-Brunell) and a close friend (Francesca Hayward), and her two male love interests (Federico Bonelli and Gary Avis). They all dance with a carefree demeanour, and engage in a youthful manner with each other. But as we approach the end of this act, those characters return and dance together in a kind of pas de cinq, weaving in and out amongst each other, joining hands at times, seemingly more closely connected to each other than in the opening moments. Then, one by one they leave the stage and Clarissa is left alone, still reflective, still solitary. But we now understand her thoughts.

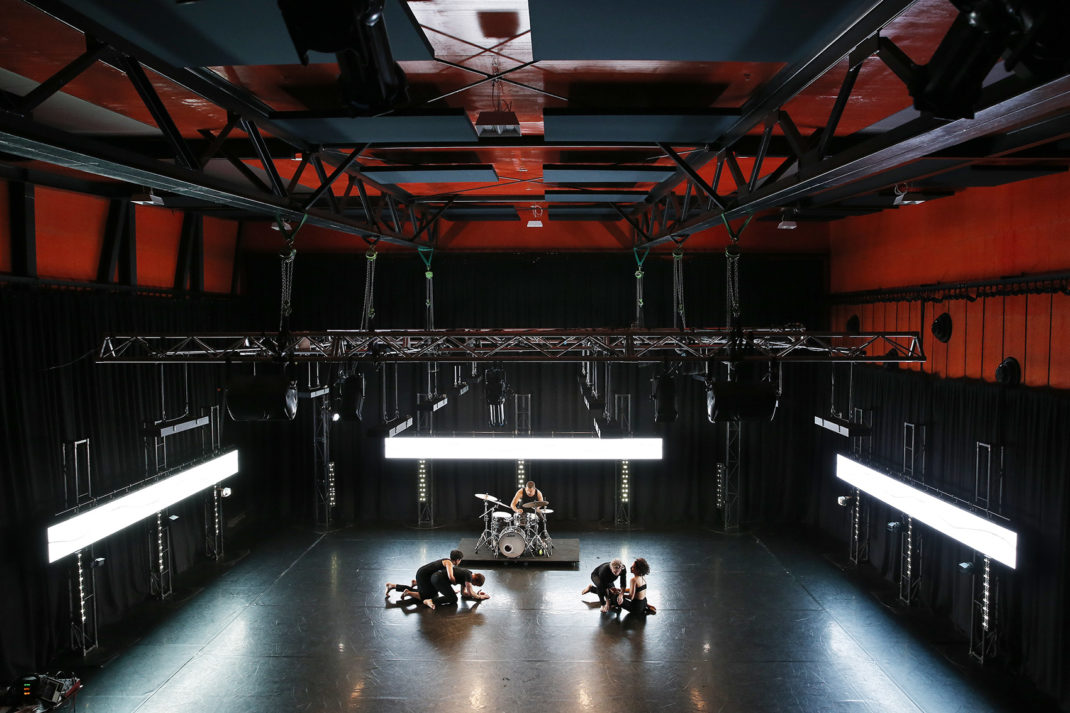

Act II: Becomings (based on Orlando)

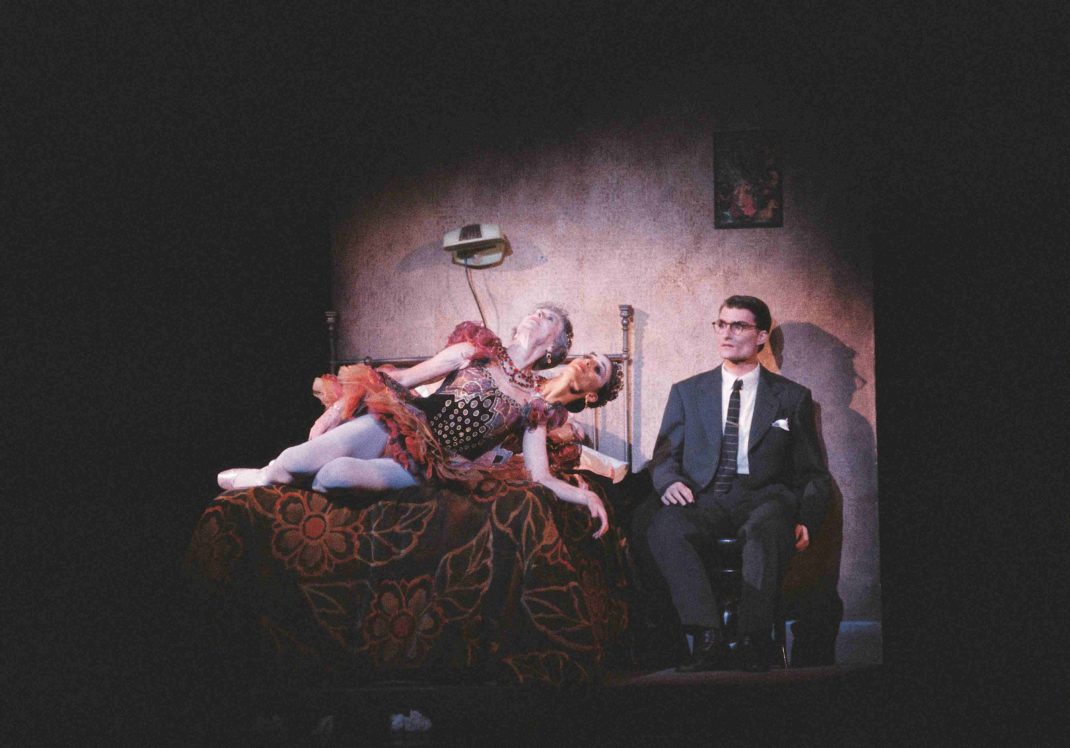

- While I was previously full of admiration for the dancing of Steven McRae, this time I was overwhelmed by his astounding abilities. Again there were some small choreographic complexities that I didn’t notice before, the suggestion of shaking legs was one, and McRae made those movements very clear. But this time I especially admired his spectacularly fluid upper body, his exceptionally flexible limbs, and the way he powered down the stage at one point to begin the next section. And his first pas de deux with Natalia Osipova was a sensational performance (from both of them).

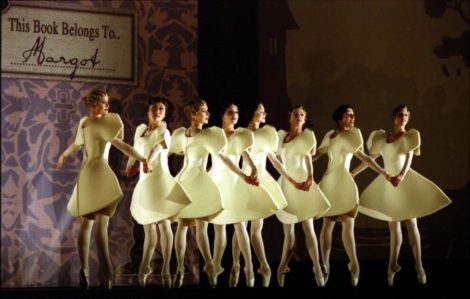

- I was struck this time too by the way in which the passing of time—the novel Orlando moves across some five centuries—was handled in the ballet. Time moved along as a result of Lucy Carter’s spectacular lighting design, but also in part with costuming. When the curtain went up all characters were wearing Elizabethan costume, but as the act developed elements of the Elizabethan attire were progressively lost. Slowly a more contemporary look became obvious. But it was a beautifully slow and changing progression so that even at the end there were still small traces of earlier times—the hint of a ruff at the neckline for example. Some things never change.

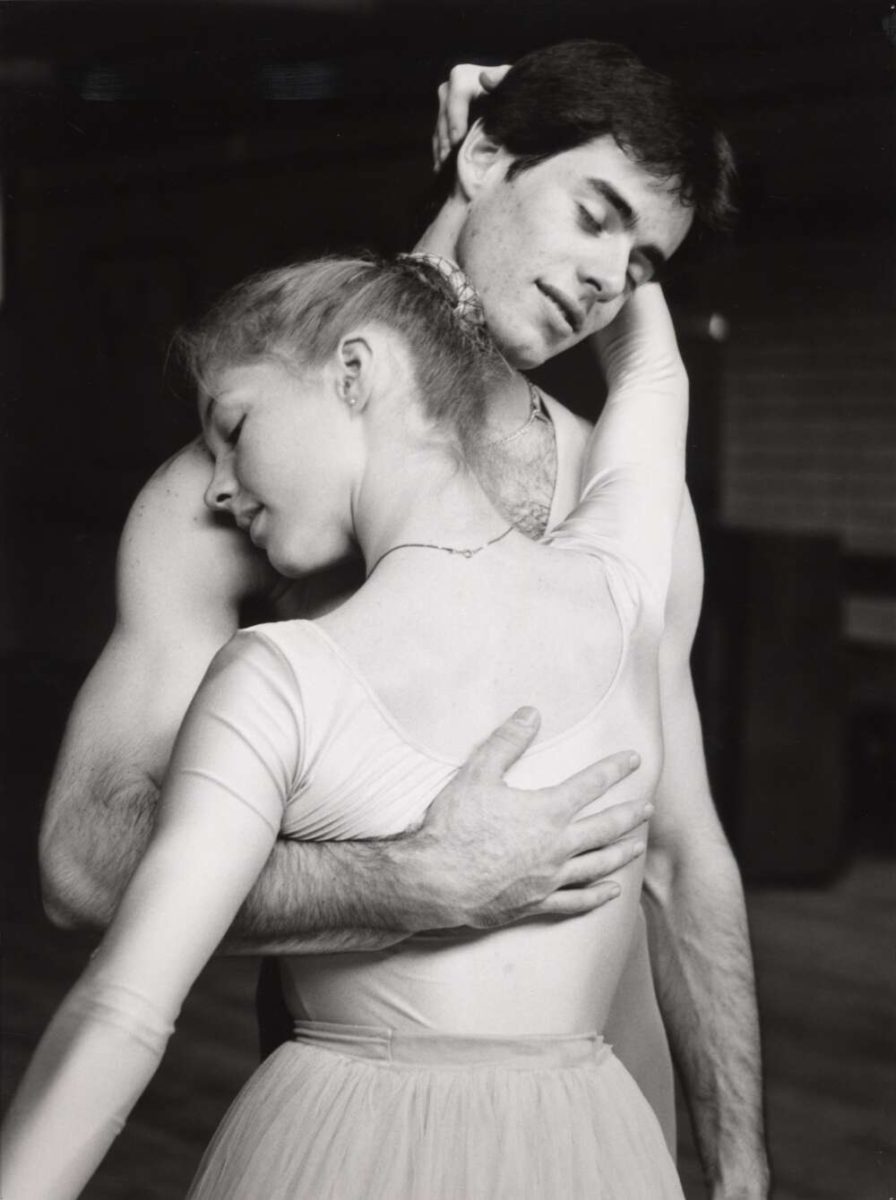

- In a similar vein, I was surprised by the way the gender changes that Orlando undergoes in the novel were addressed in the ballet. They were suggested again by costuming when small black tutu-like additions to plain contemporary costumes were worn by both male and female dancers, for example. But most startling for me was the fact that there were moments when Steven McRae seemed to take on a female role in a pas de deux. His partner was male but McRae was lifted as he had previously lifted Osipova. It was simply spectacular dancing from McRae, but my mind kept turning back to Osipova’s movements. It was a brilliant moment in the choreography.

ACT III: ‘Tuesday’ (based on The Waves)

- Again with ‘Tuesday’ I saw much more in the choreography than I had previously. This time I especially loved the opening pas de deux between Ferri and Bonelli. I watched with pleasure as he held her in his outstretched arms, carried her on his back and supported her as she lay along the side of his body. Then, in the same pas de deux, there were those captivating variations on what we have come to regard as the end pose of a regular fish dive. McGregor seems to have a mind that never sees a pose as final: there are always variations to be had.

Woolf Works is a breathtaking work of art, fabulously danced by a great company. I hope I get to see it again because I know I will continue to find more and more to ponder over, wonder at, and be moved by.

Michelle Potter, 2 July 2017

Featured image: Beatriz Stix-Brunell, Alessandra Ferri and Francesca Hayward in Woolf Works Act I (I now/I then). The Royal Ballet, Brisbane 2017. Photo: © Darren Thomas