Harry Haythorne, child performer extraordinaire, well-travelled dancer, ballet master, artistic director, teacher and mentor, has died in Melbourne aged 88.

Haythorne was the child of an English father and an Australian mother of Irish descent who met at a dance hall in Adelaide: both parents loved ballroom dancing. But they were barred from many dance halls in Adelaide because they dared to introduce what Haythorne jokingly referred to in an interview as ‘filthy foreign dances’ such as the foxtrot and the quickstep. His father had brought these dance styles with him when he migrated to Australia. They were unknown at the time in Adelaide.

Haythorne began his own dance training with Jean Bedford who taught ‘operatic dancing’ and shortly afterwards began tap classes with Herbert Noye. His initial ambitions were to go into vaudeville. Even with the arrival of the Ballets Russes in Australia in the 1930s, which was an exciting time for him, he still did not have ambitions to take up ballet seriously.

When Haythorne was about 14 he began his professional performing career with Harold Raymond’s Varieties, a Tivoli-style vaudeville group established initially as a concert party to entertain troops as World War II began. With Harold Raymond he took part in comedy sketches, played his piano accordion, sang and danced. His star act, which would feature again much later in his life, was his tap dancing routine on roller-skates.

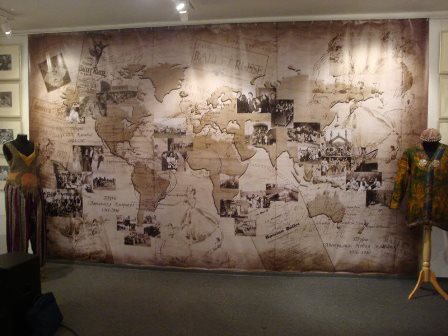

Eventually, in the late 1940s, he took ballet classes from Joanna Priest and performed in her South Australian Ballet before leaving for England. It was seeing Ballet Rambert during its Australasian tour 1947–1949 that inspired him to change direction and look to ballet as a career. In London he took classes with Anna Northcote and Stanislas Idzikowski before auditioning successfully for Metropolitan Ballet, later joining Mona Ingelsby’s International Ballet. But his career in England and Europe was an eclectic one and he also worked on the Max Bygraves Show, danced on early British television shows, performed in the Cole Porter musical Can Can and toured to South Africa with a production of The Pyjama Game.

Haythorne listed the three greatest influences on his early career as Léonide Massine, for whom he acted as personal assistant and ballet master for Massine’s company, Les ballets européens; Walter Gore, for whom he was ballet master for Gore’s London Ballet; and Peter Darrell who hired him as manager of Western Theatre Ballet and then as his assistant artistic director of Scottish Ballet in Glasgow.

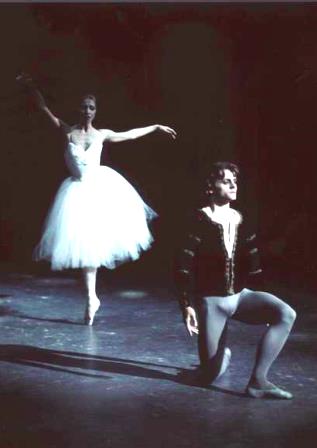

Always an Australian at heart, Haythorne began to miss his homeland and made various moves to return. He eventually came back as artistic director of Queensland Ballet, a position he took up in 1975. With Queensland Ballet he mounted works by Australian choreographers including Graeme Murphy, Garth Welch and Don Asker and had Hans Brenaa stage La sylphide and other Bournonville ballets. But it was a short directorship. Haythorne was unhappy at how his contract was terminated in 1978 and always maintained that no reason was given other than ‘boards don’t have to give reasons’. But he remained in Queensland for the next few years and worked to established the tertiary dance course at Kelvin Grove College of Advanced Education (now Queensland University of Technology).

But after deciding that he did not want to head a school but direct a company he accepted the position of artistic director of the Royal New Zealand Ballet in 1981. Haythorne’s directorship of the Royal New Zealand Ballet was a fruitful one and lasted until 1992. During his tenure the company staged works by New Zealand and Australian choreographers as well as ballets by major international artists. Haythorne oversaw the company’s 30th anniversary in 1983; toured the company to China, the United States, Australia and Europe; and staged his own, full-length Swan Lake. For the Royal New Zealand Ballet’s 60th anniversary in 2013, encapsulating his attitude to his appointment in 1981, and also his approach to directorship in general, he wrote:

I knew I had to learn much more about New Zealand and its history, familiarise myself not only with its dance world but also with its literature, music and visual arts, while still keeping a finger on the international pulse.*

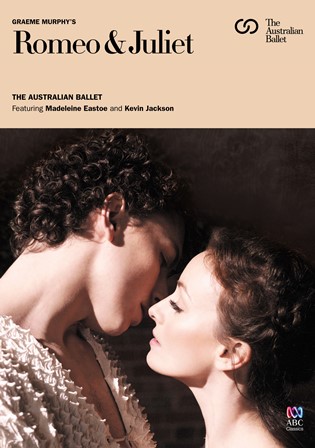

On his return to Australia in 1993 Haythorne was always in demand. He taught dance history at the Victorian College of the Arts and repertoire at the National Theatre Ballet School. He returned to the stage on several occasions with productions by the Australian Ballet, taking cameo roles in Stanton Welch’s Cinderella, Graeme Murphy’s Nutcracker and Swan Lake, Ronald Hynd’s Merry Widow, and the joint Australian Ballet/Sydney Dance company production of Murphy’s Tivoli.

Many will remember clearly his role in Tivoli where he was cast as an old vaudeville trouper and, at the age of 75, reprised his tap dancing/roller-skating/skipping routine from the 1940s. For his performances in this role he received a 2001 Australian Dance Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Dancer. I also especially enjoyed his performance as the Marquis in Act I of Murphy’s Swan Lake. His role required him to assemble guests at the wedding into various groups and to photograph them using an old camera on a tripod. Much of this action took place upstage outside of the main activities. But Haythorne made the role his own and his interactions with the guests, including the children who were part of the crowd, were always fascinating and he never paused to stand and watch what was happening downstage.

But perhaps my fondest memory is of sitting in his Melbourne flat after recording an interview with Robin Haig, who was staying with him at the time. Harry got out a bottle of wine and some huge goblets that looked like they could have been a prop from Swan Lake. After a glass or two and much talk and laughter I realised that my plane home to Canberra had already departed. Consternation! Several hurried phone calls later a taxi arrived. I was hustled into the taxi, we sped down the freeway and I made the next plane.

Harry Haythorne: born Adelaide, 7 October 1926; died Melbourne, 24 November 2014

* Harry Haythorne quoted in Jennifer Shennan and Anne Rowse, The Royal New Zealand Ballet at Sixty (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2013), p. 86

Michelle Potter, 25 November 2014

Featured image: Harry Haythorne, c. 2000. Photographer unknown

UPDATE: See Jennifer Shennan’s tribute to Harry Haythorne at this link.