22 March 2012, St James Theate, Wellington

The first program by new artistic director of Royal New Zealand Ballet, Ethan Stiefel, opened in Wellington on 22 March. After a regional tour that began in Auckland in February the program, NYC: three short works from the Big Apple, had clearly worked itself into a very smooth operation by the time it reached Wellington. We saw a diverse, exuberant and beautifully danced show.

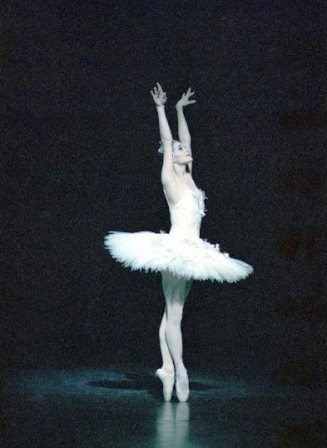

The program opened with 28 variations on a theme by Paganini, a work by Benjamin Millepied made originally in 2005. Danced to a piano score by Brahms, the choreography is as varied as the music. Under a single chandelier, and against a black background, five elegantly dressed couples whirl and swirl across the stage. Sometimes they dance in canon, often they execute fabulous lifts and move with unexpected changes of direction. They engage in a luscious performance of the classical vocabulary and occasionally there are subtle undercurrents that suggest relationships between them. I especially enjoyed the dancing of Bronte Kelly whose pleasure in being in this very dancerly work was patently clear.

There were, however, a few moments when for me the choreography was jarring. At one point Gillian Murphy entered walking on pointe, stiff-legged and looking a little like a dancer-doll who had suddenly stepped off a music box. Not even Murphy’s strong onstage presence and expressive face could save this section from looking out of place.

Taking the middle spot on the program was Larry Keigwin’s Final dress, created especially for the Royal New Zealand Ballet and danced to a fast-paced score for violin, cello, clarinet and electric piano by Adam Crystal. On a stage stripped right back to basics, this work is full-on dancing from beginning to end. Mixing contemporary movement with more classical steps, the dancers explore the adrenalin rush associated with getting a show onstage. They run, throw themselves at each other and exude constant energy. I didn’t read into it what the program note told me it was about, ‘the boundaries between the public and the private, and the territories we guard’, but Final dress deservedly got a loud and enthusiastic reception as it came to an end.

Closing the evening was a performance of the vintage Balanchine work Who cares? set to a Hershey Kay arrangement of songs by George Gershwin. This is sassy Balanchine in his Hollywood/Broadway mode and to a certain extent it is a little outdated in terms of the dance style and era it references: it is four decades old, compared with later works in a similar vein such as Twyla Tharp’s Nine Sinatra Songs (made a mere two decades ago). But that aside, the dancers of the Royal New Zealand Ballet did themselves proud. Gillian Murphy and Paul Mathews danced an as smooth as silk pas de deux and the two other soloists, Abigail Boyle and Lucy Green, shone like Hollywood stars. I also admired the lovely-limbed dancer, Maree White, who took the middle spot in the line-up of the five chorus ladies.

A small grumble about the printed program: why didn’t it contain costume design credits? There wasn’t much to worry about with sets as there weren’t really any to fuss about, other than the New York skyline (minus the Chrysler Building) for Who cares? But the costume designers did deserve a billing, even if some costumes were apparently hired from New York-based ballet companies. Someone must have designed them. And why were there no captions for photos in the program? For those who are not regulars at Royal New Zealand Ballet performances it would have been nice if the dancers in some lovely photographs had been identified. But NYC was a wonderful start for Stiefel’s directorship and the prospect of more is definitely something to anticipate.

Michelle Potter, 23 March 2012