- Garry Stewart to leave Australian Dance Theatre

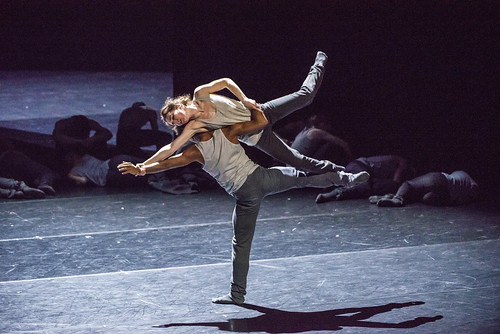

I have to admit to being slightly taken aback when I heard that Garry Stewart would relinquish his directorship of Australian Dance Theatre at the end of 2021. He leaves behind an incredible legacy I think. My first recollection of his choreography goes back to the time in the 1990s when he was running a company called Thwack! I recall in particular a production called Plastic Space, which was shown at the 1999 Melbourne Festival. It examined our preoccupation with aliens and I wrote in The Canberra Times, ‘[Stewart’s] dance-making is risky, physically daring and draws on a variety of sources….’ I also wrote program notes for that Melbourne Festival and remarked on three preoccupations I saw in his work. They were physical virtuosity, thematic abstraction and technology as a choreographic tool. Most of Stewart’s work that I have seen with ADT has continued to embody those concepts.

Although since the 1990s I have seen fewer Stewart works than I would have liked, the three that have engaged me most of all have been G (2008), Monument (2013), which I regret was never seen outside Canberra, and The Beginning of Nature (2018), which won the 2018 Australian Dance Award for Outstanding Performance by a Company.

At this stage I don’t know where life will lead Garry Stewart after 2021 but I wish him every success. His contribution to dance in Australia has been exceptional.

- Marguerite and Armand. The Royal Ballet Digital Season

The last time I saw Frederick Ashton’s Marguerite and Armand, made in 1963 for Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, was in 2018. Then I had the good fortune to see Alessandra Ferri and Federico Bonelli leading a strong Royal Ballet cast. It was in fact the standout performance on a triple bill. I also remember seeing a remarkable performance by Sylvia Guillem as Marguerite when the Royal visited Australia in 2002, although I was not so impressed with her partners. (I saw two performances with different dancers taking the male role on each of those occasions).

The streamed performance offered by the Royal Ballet recently featured Zenaida Yanowsky and Roberto Bolle. It was filmed in 2017 and was Yanowsky’s farewell performance with the Royal Ballet. She is a strong technician and a wonderful actor and her performance was exceptional in both those areas. Yet, I was somewhat disappointed. Bolle was perhaps not her ideal partner. Yanowsky is quite tall and seemed at times to overpower Bolle. But in addition I found her take on the role a little cold. She was extraordinarily elegant but I missed a certain emotional, perhaps even guileless quality that I saw in Ferri and Guillem.

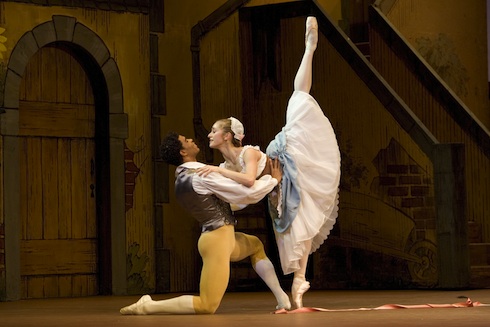

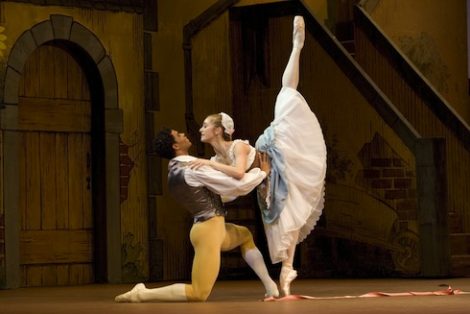

- La Fille mal gardée. The Royal Ballet

The Royal Ballet is once more streaming a performance of Frederick Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée, this time featuring Steven McRae and Natalia Osipova in the leading roles. But, as I was investigating the streaming conditions and watching the trailer, I came across a twelve minute mini-documentary about the ballet, focusing especially on its English qualities. It is a really entertaining and informative twelves minutes and includes footage of the beautifully groomed white pony, called Peregrine, who has a role in the ballet. We see him entering the Royal Opera House via the stage door and climbing the stairs to the stage area. Isn’t there a adage that says never share the stage with children or animals? Well Peregrine steals the show in this documentary! But there are many other moments of informative and lively discussion about the ballet and the documentary is worth watching. Link below.

- The Australian Ballet on the International Stage. Lisa Tomasetti’s new book

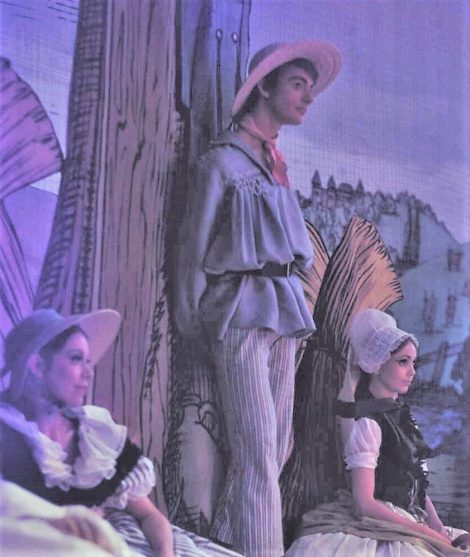

Lisa Tomasetti is a photographer whose work I have admired for some time. She has a great eye for catching an unusual perspective on whatever she photographs. Late in 2020 she issued a book of photographs of the Australian Ballet on various of its international tours, including visits to London, New York (and elsewhere in the United States), Beijing, Tokyo and Paris. This book of exceptional images is available from Tomasetti’s website at this link.

- Coming in April: The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Ballet

The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Ballet has been a long-time in production but it will be released in April. The book is extensive in scope with a wide list of contributors including scholars, critics and choreographers from across the world. Here is a link to information about the publication. The list of contents, extracted from the link, is at the end of this post.

- Sir Robert Cohan (1925-2021)

I was sorry to hear that Sir Robert Cohan had died recently. He made a huge impact on contemporary dance and its development in the United Kingdom, and his influence on many Australian dancers and choreographers, including Sydney-based artists Patrick Harding-Irmer and Anca Frankenhaeuser, was exceptional. An obituary in The Guardian, written by Jane Pritchard, is at this link.

- Kristian Fredrikson. Designer. More reviews and comments

The Canberra Times recently published a review of Kristian Fredrikson. Designer in its Saturday supplement, Panorama. The review was written by Emeritus Professor of Art History at the Australian National University, Sasha Grishin. Here is the review as it appeared in the print run of the paper on 16 January 2021.

The review is also available online at this link and is perhaps easier to read there.

Michelle Potter, 31 January 2021

Featured image: Garry Stewart. Photo: © Meaghan Coles (www.nowandthenphotography.com.au)

CONTENTS FOR THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF CONTEMPORARY BALLET

Acknowledgments

About the Contributors

Introduction

On Contemporaneity in Ballet: Exchanges, Connections, and Directions in Form

Kathrina Farrugia-Kriel and Jill Nunes Jensen

Part I: Pioneers, or Game Changers

Chapter 1: William Forsythe: Stuttgart, Frankfurt, and the Forsythescape

Ann Nugent

Chapter 2: Hans van Manen: Between Austerity and Expression Anna Seidl

Chapter 3: Twyla Tharp’s Classical Impulse

Kyle Bukhari

Chapter 4: Ballet at the Margins: Karole Armitage and Bronislava Nijinska

Molly Faulkner and Julia Gleich

Chapter 5: Maguy Marin’s Social and Aesthetic Critique

Mara Mandradjieff

Chapter 6: Fusion and Renewal in the Works of Jiří Kylián

Katja Vaghi

Chapter 7: Wayne McGregor: Thwarting Expectation at The Royal Ballet

Jo Butterworth and Wayne McGregor

Part II: Reimaginings

Chapter 8: Feminist Practices in Ballet: Katy Pyle and Ballez

Gretchen Alterowitz

Chapter 9: Contemporary Repetitions: Rhetorical Potential and The Nutcracker

Michelle LaVigne

Chapter 10: Mauro Bigonzetti: Reimagining Les Noces (1923)

Kathrina Farrugia-Kriel

Chapter 11: New Narratives from Old Texts: Contemporary Ballet in Australia

Michelle Potter

Chapter 12: Cathy Marston: Writing Ballets for Literary Dance(r)s

Deborah Kate Norris

Chapter 13: Jean-Christophe Maillot: Ballet, Untamed

Laura Cappelle

Chapter 14: Ballet Gone Wrong: Michael Clark’s Classical Deviations

Arabella Stanger

Part III: It’s Time

Chapter 15: Dance Theatre of Harlem: Radical Black Female Bodies in Ballet

Tanya Wideman-Davis

Chapter 16: Huff! Puff! And Blow the House Down: Contemporary Ballet in South Africa

Gerard M. Samuel

Chapter 17: The Cuban Diaspora: Stories of Defection, Brain Drain and Brain Gain

Lester Tomé

Chapter 18: Balancing Reconciliation at The Royal Winnipeg Ballet

Bridget Cauthery and Shawn Newman

Chapter 19: Ballet Austin: So You Think You Can Choreograph

Caroline Sutton Clark

Chapter 20: Gender Progress and Interpretation in Ballet Duets

Jennifer Fisher

Chapter 21: John Cranko’s Stuttgart Ballet: A Legacy

E. Hollister Mathis-Masury

Chapter 22: “Ballet” Is a Dirty Word: Where Is Ballet in São Paulo?

Henrique Rochelle

Part IV: Composition

Chapter 23: William Forsythe: Creating Ballet Anew

Susan Leigh Foster

Chapter 24: Amy Seiwert: Okay, Go! Improvising the Future of Ballet

Ann Murphy

Chapter 25: Costume

Caroline O’Brien

Chapter 26: Shapeshifters and Colombe’s Folds: Collective Affinities of Issey Miyake and William Forsythe

Tamara Tomić-Vajagić

Chapter 27: On Physicality and Narrative: Crystal Pite’s Flight Pattern (2017)

Lucía Piquero Álvarez

Chapter 28: Living in Counterpoint

Norah Zuniga Shaw

Chapter 29: Alexei Ratmansky’s Abstract-Narrative Ballet

Anne Searcy

Chapter 30: Talking Shop: Interviews with Justin Peck, Benjamin Millepied, and Troy Schumacher

Roslyn Sulcas

Part V: Exchanges Inform

Chapter 31: Royal Ballet Flanders under Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

Lise Uytterhoeven

Chapter 32: Akram Khan and English National Ballet

Graham Watts

Chapter 33: The Race of Contemporary Ballet: Interpellations of Africanist Aesthetics

Thomas F. DeFrantz

Chapter 34: Copy Rites

Rachana Vajjhala

Chapter 35: Transmitting Passione: Emio Greco and the Ballet National de Marseille

Sarah Pini and John Sutton

Chapter 36: Narratives of Progress and Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal

Melissa Templeton

Chapter 37: Mark Morris: Clarity, a Dash of Magic, and No Phony Baloney

Gia Kourlas

Part VI: The More Things Change . . .

Chapter 38: Ratmansky: From Petipa to Now

Apollinaire Scherr

Chapter 39: James Kudelka: Love, Sex, and Death

Amy Bowring and Tanya Evidente

Chapter 40: Liam Scarlett: “Classicist’s Eye . . . Innovator’s Urge”

Susan Cooper

Chapter 41: Performing the Past in the Present: Uncovering the Foundations of Chinese Contemporary Ballet

Rowan McLelland

Chapter 42: Between Two Worlds: Christopher Wheeldon and The Royal Ballet

Zoë Anderson

Chapter 43: Christopher Wheeldon: An Englishman in New York

Rachel Straus

Chapter 44: The Disappearance of Poetry and the Very, Very Good Idea

Freya Vass

Chapter 45: Justin Peck: Everywhere We Go (2014), a Ballet Epic for Our Time

Mindy Aloff

Part VII: In Process

Chapter 46: Weaving Apollo: Women’s Authorship and Neoclassical Ballet

Emily Coates

Chapter 47: What Is a Rehearsal in Ballet?

Janice Ross

Chapter 48: Gods, Angels, and Björk: David Dawson, Arthur Pita, and Contemporary Ballet

Jennie Scholick

Chapter 49: Alonzo King LINES Ballet: Voicing Dance

Jill Nunes Jensen

Chapter 50: Inside Enemy

Thomas McManus

Chapter 51: On “Contemporaneity” in Ballet and Contemporary Dance: Jeux in 1913 and 2016

Hanna Järvinen

Chapter 52: Reclaiming the Studio: Observing the Choreographic Processes of Cathy Marston and Annabelle Lopez Ochoa

Carrie Gaiser Casey

Chapter 53: Contemporary Partnerships

Russell Janzen

Index