The discussion of the Australian Ballet and its visits to Canberra, or lack of them over recent years, has become very tedious. This morning The Canberra Times published yet another piece relating to the problems of presenting the Australian Ballet in Canberra.

‘The ballet company’s stunning performances of Romeo and Juliet and new versions of Swan Lake that drew rapturous praise in other parts of Australia could not be staged in the ACT because of a lack of a venue’, the article stated.

The article was wider in scope than a simple discussion of the difficulties faced by the Australian Ballet and was basically a plea for a bigger, better theatre. I agree it would be wonderful to have a new theatre that wasn’t the butt of complaints and that could take larger shows than the present theatre can adequately handle. But what do we do in the meantime? A new theatre will probably be built eventually but, like the very fast train, it may be a long time coming.

Does Canberra really have to be by-passed by the Australian Ballet as has happened over recent years? And yes, I know we had Telstra Ballet in the Park last year—and what a huge audience it attracted on a very inclement evening. And we’ve had a few tidbits as part of a couple of Canberra Symphony Orchestra matinee programs. But not many main-stage events recently.

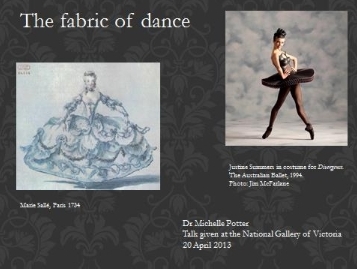

The Australian Ballet’s 2013 Canberra program, opening shortly, is interesting in this regard. All three works on the program are relatively small scale in terms of the cast required. The pas de deux from Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain is just that, a pas de deux, a dance for two (the complete ballet is cast for just six dancers). George Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments is cast for twenty-five dancers although they all come together only briefly at the end of the work. Garry Stewart’s new work Monument is, I understand, made for nineteen dancers. None of these three works needs a full orchestra; none is complemented by a huge set or needs masses of props. What’s wrong with the Australian Ballet coming on an annual basis and bringing this kind of ‘chamber’ repertoire?

The Australian Ballet at present has a ballet mistress and repetiteur who is an experienced stager of the works of George Balanchine. So many Balanchine ballets fall into this ‘chamber’ category, and what remarkable ballets they are. Graeme Murphy, Stanton Welch and Stephen Baynes have all made works for the Australian Ballet that don’t have huge casts and elaborate sets and costumes. The list is endless. Way, way back Canberra was even the venue for the culmination of the Australian Ballet’s Choreographic Workshop program. Graeme Murphy’s beautifully sensual one act ballet Glimpses, depicting the world of artist Norman Lindsay and danced to Margaret Sutherland’s score Haunted Hills, had its premiere on one such occasion. Why not give Canberra back its annual visit and give it a program made up of works that suit the stage space, that are do-able in Canberra, rather than constantly returning to the chestnut of the facilities not being up to scratch? Let’s get over the prevailing attitude and look for what can happen, rather than what can’t.

What’s wrong with at least giving a ‘chamber’ program a go for a few years to gauge audience reaction? And of course the media have to write about it positively and intelligently so that it doesn’t seem that Canberra is only getting these works because the big ones can’t fit.

As for Swan Lake and Romeo and Juliet, well there’s more to the Australian Ballet, and to ballet as an art form, than large scale works like these two, which in their most recent Australian Ballet manifestations didn’t draw ‘rapturous praise’ everywhere anyway. That’s a bit of hype, even though both works were thought-provoking and certainly worth seeing. And anyway for those hankering after blockbusters, Sydney is not far away while we wait for a new theatre. Plenty of us make the trip.

Michelle Potter, 4 May 2013

Symmetries, the Canberra triple bill from the Australian Ballet

23–25 May 2013. Canberra Theatre Centre