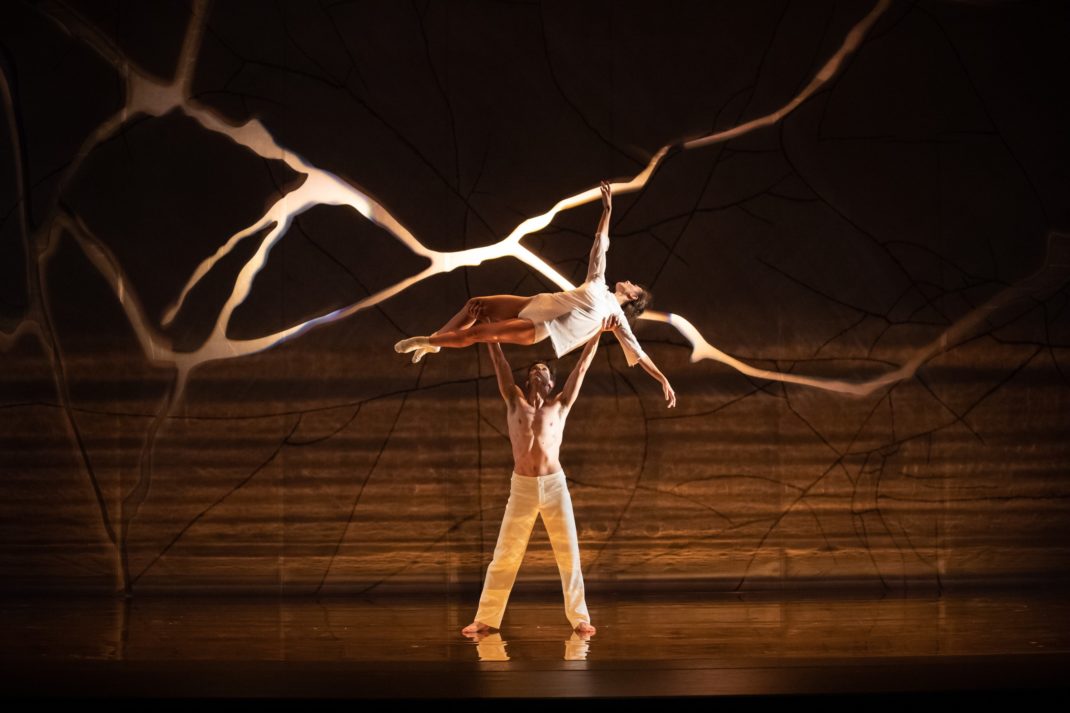

Alice Topp’s Aurum

Aurum, choreographed by Alice Topp, a resident choreographer with the Australian Ballet, was first seen in Melbourne in 2018. It was followed by a 2019 season in Sydney, a scene from which is the featured image for this post. Also in 2019 it had a showing in New York at the Joyce Theater. In fact the Joyce was in part responsible for the creation of Aurum. Aurum was enabled with the support of a Rudolf Nureyev Prize for New Dance, awarded by the Joyce. Major funding came from the Rudolf Nureyev Dance Foundation. Aurum went on to win a Helpmann Award in 2019.

Now Topp will stage her work for Royal New Zealand Ballet as part of that company’s Venus Rising program opening in May 2020. She has recently been rehearsing the work in RNZB studios in Wellington.

I can still feel the excitement of seeing Aurum for the first time in 2018 when it was part of the Australian Ballet’s Verve program. My review from that season is at this link.

Dance Australia critics’ survey

Below are my choices in the annual Dance Australia critics’ survey. See the February/March 2020 issue of Dance Australia for the choices made by other critics across Australia. The survey is always interesting reading.

- Highlight of the year

West Side Story’s return to Australian stages looking as fabulous as it did back in the 1960s. A true dance musical in which choreographer Jerome Robbins tells the story brilliantly through dance and gesture.

- Most significant dance event

Sydney Dance Company’s 50th anniversary. Those who have led, and are leading the company—Suzanne Musitz, Jaap Flier, Graeme Murphy and Janet Vernon, and currently Rafael Bonachela—have given Australian audiences a varied contemporary repertoire with exposure to the work of some remarkable Australian choreographers and composers, as well as the work of some of the best contemporary artists from overseas.

- Most interesting Australian independent group or artist

Canberra’s Australian Dance Party, which has started to develop a strong presence and unique style and has given Canberra a much needed local, professional company. The 2019 production From the vault showed the company’s strong collaborative aesthetic with an exceptional live soundscape and lighting to add to the work’s appeal.

- Most interesting Australian group or artist

Bangarra Dance Theatre. Over thirty years the company has gone from strength to strength and can only be admired for the way in which Stephen Page and his associates tell Indigenous stories with such pride and passion.

- Most outstanding choreography

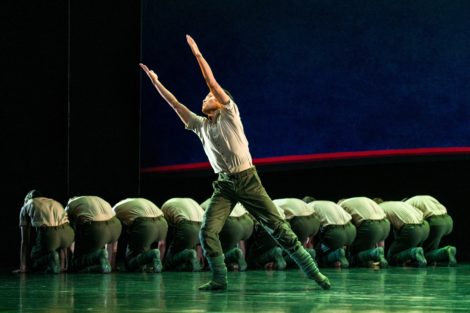

Melanie Lane’s thrilling but somewhat eccentric WOOF as restaged by Sydney Dance Company. It was relentless in its exploration of group behaviour and reminded me a little of a modern day Rite of Spring

- Best new work

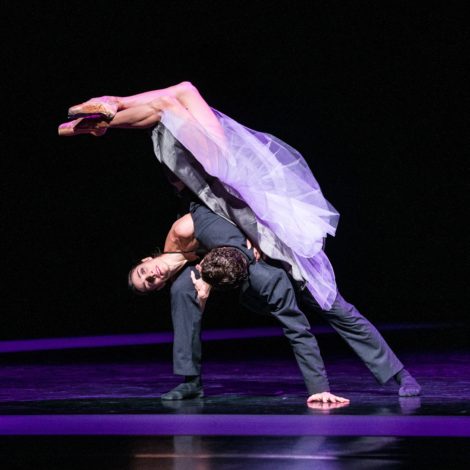

Dangerous Liaisons by Liam Scarlett for Queensland Ballet. Scarlett has an innate ability to compress detail without losing the basic elements of the narrative and to capture mood and character through movement. It was beautifully performed by Queensland Ballet and demonstrated excellence in its collaborative elements.

- Most outstanding dancer(s)

Kohei Iwamato from Queensland Ballet especially for his dancing in Dangerous Liaisons as Azolan, valet to the Vicomte de Valmont. His dancing was light, fluid, and technically exact and he made every nuance of Scarlett’s choreography clearly visible

Tyrel Dulvarie in Bangarra’s revival of Unaipon in which he danced the role of David Unaipon. His presence on stage was imposing throughout and his technical ability shone, especially in the section where he danced as Tolkami (the West Wind).

- Dancer(s) to watch

Ryan Stone, dancer with Alison Plevey’s Canberra-based Australian Dance Party (ADP). His performance in ADP’s From the vault was exceptional for its fluidity and use of space and gained him a Dance Award from the Canberra Critics’ Circle.

Yuumi Yamada of the Australian Ballet whose dancing in Stephen Baynes Constant Variants and as the Daughter in Stanton Welch’s Sylvia showed her as an enticing dancer with much to offer as she develops further.

- Boos!

The Australian Government’s apparent disinterest in the arts and in the country’s collecting institutions. The removal of funding for Ausdance National, for example, resulted in the cancellation of the Australian Dance Awards, while the efficiency dividend placed on collecting institutions, which has been in place for years now, means that items that tell of our dance history lie unprocessed and uncatalogued, and hence are unusable by the public for years.

- Standing ovation

I’m standing up and cheering for the incredible variety of dance that goes on beyond our major ballet and contemporary companies. Youth dance, community dance, dance for well-being, dance for older people, and more. It is indicative of the power that dance has to develop creativity, health and welfare, and a whole range of social issues.

New oral history recordings

In January I had the pleasure of recording two new oral history interviews for the National Library of Australia’s oral history program. The first was with Chrissa Keramidas, former dancer with the Australian Ballet, American Ballet Theatre and Sydney Dance Company. Keramidas recently returned as a guest artist in the Australian Ballet’s recent revival of Nutcracker. The story of Clara. The second was with Emeritus Professor Susan Street, AO, dance educator over many years including with Queensland University of Technology and the Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts.

News from James Batchelor

James Batchelor’s Redshift, originally commissioned by Chunky Move in 2017, will have another showing in Paris in February as part of the Artdanthé Festival. Redshift is another work emerging from Batchelor’s research following his taking part in an expedition to Heard and McDonald Islands in the sub-Antarctic in 2016. Artdanthé takes place at the Théâtre de Vanves and Batchelor’s works have been shown there on previous occasions.

Batchelor is also about to start work on a new piece, Cosmic Ballroom, which will premiere in December 2020 at another international festival, December Dance, in Bruges, Belgium. Below are some of Batchelor’s thoughts about this new work.

Set in a 19th Century Ballroom in Belgium, Cosmic Ballroom will playfully reimagine social dances and the aesthetic relationship they have to the space and time they exist within. We will work with movement as a plastic and expressive language that is formed through social encounters: the passing of thoughts, feelings and uncertainties from body to body. It will ponder the public and private and the personal and interpersonal as tonal zones that radiate and contaminate. How might movement be like a virus in this context? How might space-times be playfully spilling across and infecting one another from the baroque ballroom to the post-industrial club space?

Batchelor will collaborate with an team of Australian, Italian and UK artists on this work.

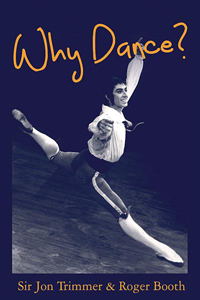

Liam Scarlett

Michelle Potter, 31 January 2020

Featured image: Andrew Killian and Dimity Azoury in Aurum. The Australian Ballet, 2019. Photo: © Daniel Boud