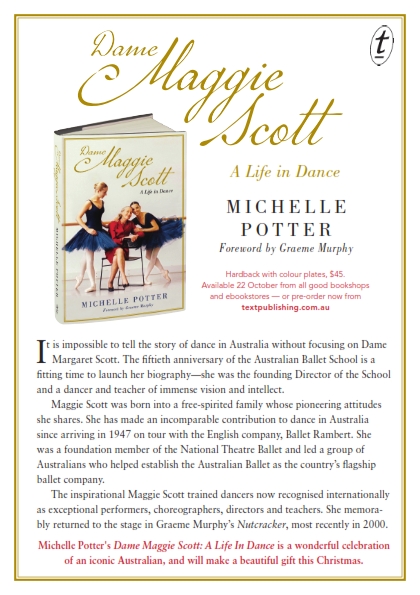

Towards the end of research for my forthcoming publication, Dame Maggie Scott: a life in dance, an item relating to Joanna Priest’s ballet The Listeners emerged, quite unexpectedly. I had briefly looked into The Listeners as it was one of the ballets performed during the opening season by the National Theatre Ballet in Melbourne in September 1949. This was the occasion when Dame Margaret Scott made her return to the stage, following a lengthy stay in St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, during the 1947—1949 Australasian tour by Ballet Rambert.

The appearance of this previously unknown item (unknown to me anyway) prompted me to look at The Listeners in a little more depth. My main source for further investigation was a Laban score for the work, part of the small collection of notated scores acquired by the National Library of Australia from Meg Abbie Denton in around 2004. Further information came from Meg’s publication Joanna Priest: her place in Adelaide’s dance history (Adelaide: Joanna Priest, 1993), and Alan Brissenden’s and Keith Glennon’s Australia dances: creating Australian dance 1945–1965 (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2010).

The Listeners was first staged for the South Australian Ballet Club in Adelaide on 30 November 1948 at the Tivoli Theatre (later Her Majesty’s). It was inspired by a poem written by Walter de la Mare, and Priest used the poem’s title as the name of her ballet. It was performed to Erno Dohnanyi’s String Quartet No 2 in D flat major, Opus 15, played by the Elder String Quartet, and had designs by Kenneth Rowell, his second commission from Priest.

In the poem, the only human is a traveller who knocks on the door of a deserted house, deserted except for ‘a host of phantom listeners’ who do not respond to him. For her work, Priest added two women in the traveller’s life—one who loved him, the other whom he loved—as well as the child who was born from the liaison between the traveller and the woman who loved him. They were joined by the force of circumstance represented by four female dancers. Program notes explain:

The traveller arrives at an abandoned house which holds intimate memories…and here among “a host of phantom listeners” the conflict of his relationship with two women is re-enacted in his imagination. Dogged by the relentless interference of circumstance he tries in vain to weave into an enduring pattern his longing for the woman he loves, and his loyalty to the woman who has borne him a child. The harmony of the pattern is perpetually broken by inexorable forces, and, as in life, his struggles against them prove unavailing.

In the original production Harry Haythorne danced the Traveller, Margaret Monson the Woman who Loved Him, and Lynette Tuck the Woman He Loved.

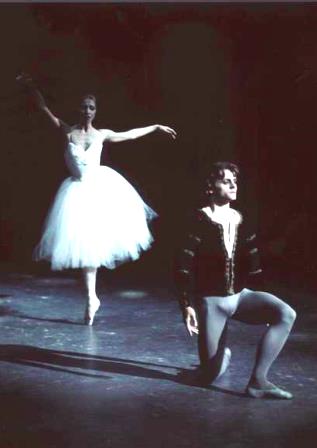

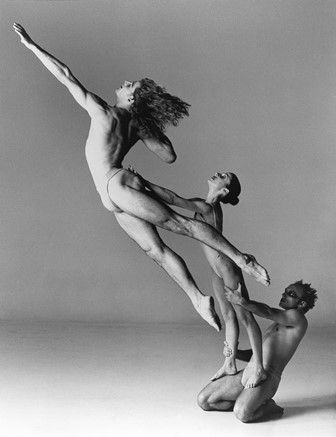

The ballet entered the repertoire of the National Theatre Ballet in 1949 with Rex Reid as the Traveller, Joyce Graeme as the Woman who Loved Him, Margaret Scott as the Woman He Loved and Jennifer Stielow as the Child. Six extra dancers were added, three men and three women, representing phantom listeners. Kenneth Rowell designed new sets and costumes for this production.

Alan Brissenden’s report of the National’s production has a number of errors, in particular some confusion as to which roles were danced by whom, but of the overall production he says:

The complex choreography followed the melodic structure of the music…and was firmly knit with the development of the story.

What is the unexpected item? It will appear in the plates section of Dame Maggie Scott: a life in dance.

Michelle Potter, 14 August 2014

Featured image: Joyce Graeme as the Woman who Loved Him and Jennifer Stielow as the Child in The Listeners, National Theatre Ballet, 1949. Photo: Harry Jay