11 May 2013 (matinee & evening), Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House (The Four Temperaments, Bella Figura, Dyad 1929)

If this triple bill program from the Australian Ballet did one thing it was to show how far ahead of his time George Balanchine was in 1946 when he made The Four Temperaments.

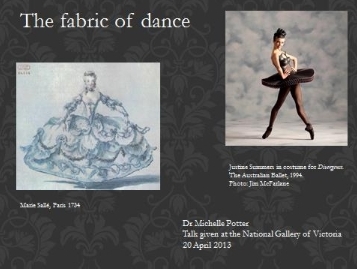

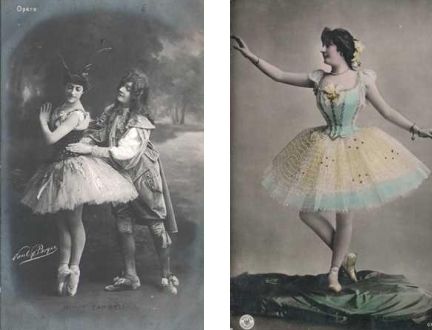

Although the title, The Four Temperaments, suggests a link to the ancient practice of assigning behavioural characteristics to humans based on the extent to which certain fluids are present in the body, I think this is essentially an abstract ballet. It deconstructs classical ballet vocabulary before the idea of deconstruction in arts practice became a trendy phenomenon. So many of the movements—Balanchine’s different examples of supported pirouettes for example—show by the very act of deconstruction how the vocabulary of ballet is constructed. In addition, Balanchine’s use of turned in feet and legs, forward-thrusting pelvic movements, stabbing movements by the women on pointe, angular shapes made with the arms and palms of the hand, are all beyond what the eye is accustomed to think of as pure, classical movement. But seen within the context of the entire ‘Vanguard’ program, it is clear that similar movements surface in the work of choreographers coming after Balanchine. Such an attitude to the balletic vocabulary is especially noticeable in the choreography for Dyad 1929 made by Wayne McGregor in 2009.

Balanchine made his move in 1946 (at least) and I think the different look Dyad 1929 and others of McGregor’s works have, which is certainly a look more in keeping with the twenty first century, is as much a reflection of technical developments and changes in body shape since 1946 as anything else. The Four Temperaments is really a remarkable work.

The Australian Ballet has been beautifully coached and rehearsed for The Four Temperaments. There was a simple elegance and a clarity of technique in their dancing and they made the choreographic design very clear. At times, however, I wished some parts had been slightly more exaggerated—the movement in the pelvis for example. Balanchine was a showy choreographer at times and I think a little of the showiness that American companies seem to add to The Four Temperaments was missing.

Of the two casts I saw I most admired Daniel Gaudiello in the ‘Melancholic’ variation. I loved his unexpected falls, the theatrical way he threw his arms around his body, his very fluid movement, and his wonderful bend back from the waist as he made his (backwards) exit. I also enjoyed the pert and precise quality Ako Kondo and Chengwu Guo brought to ‘Theme II’ and Juliet Burnett’s languorous and smooth flowing work in ‘Theme III’. Of the corps Dana Stephensen and Brooke Lockett (in different casts) stood out for me in supporting roles in ‘Melancholic’.

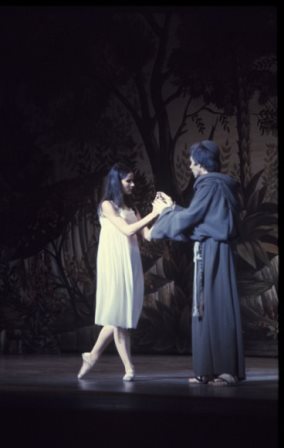

Then came Jiri Kylian’s emotive work Bella Figura with its mysterious lighting and half-revealed spaces.

Bella was first performed by the Australian Ballet in 2000 when it had a more than memorable cast, and it has been restaged in the intervening period, again with strong casts. So it is a pleasure to record that one cast I saw on this occasion did not make me think back to other performances. It even opened up for me a new view of the piece. The closing duet, danced in silence by Lana Jones and Daniel Gaudiello, in moody lighting with two braziers burning brightly in the background, was moving, intimate and deeply satisfying. What wonderful rapport these two dancers have and how affecting is their ability to project that rapport so strongly. Jones and Gaudiello were also outstanding in another duet earlier on in the work. I don’t remember such a comic element in that particular duet on previous occasions; this time it bordered on the slapstick. But it was brilliantly done as Jones and Gaudiello managed to retain ‘la bella figura’ in its best sense, while also making us laugh.

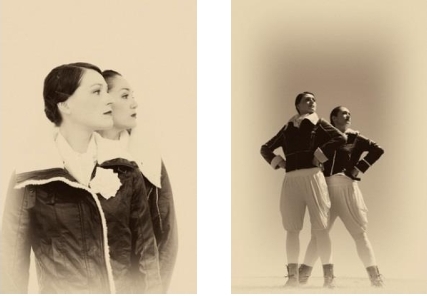

After these two works Dyad 1929 looked very thin to me. I have admired recent works by Wayne McGregor including his Chroma, FAR and Live fire exercise, and I was also impressed by Dyad 1929 when it was first shown in Australia in 2009. This time I didn’t get the feeling that the dancers saw any diversity within the work. They all performed the steps very nicely but brought little else. After The Four Temperaments and Bella Figura it was a disappointment, not so much choreographically as in terms of performance.

Michelle Potter, 13 May 2013

Featured image: Andrew Killian, Lana Jones and Daniel Gaudiello in Dyad 1929. The Australian Ballet, 2013. Photo: © Branco Gaica